Mind and Iron: A propaganda expert has a dire warning for this country

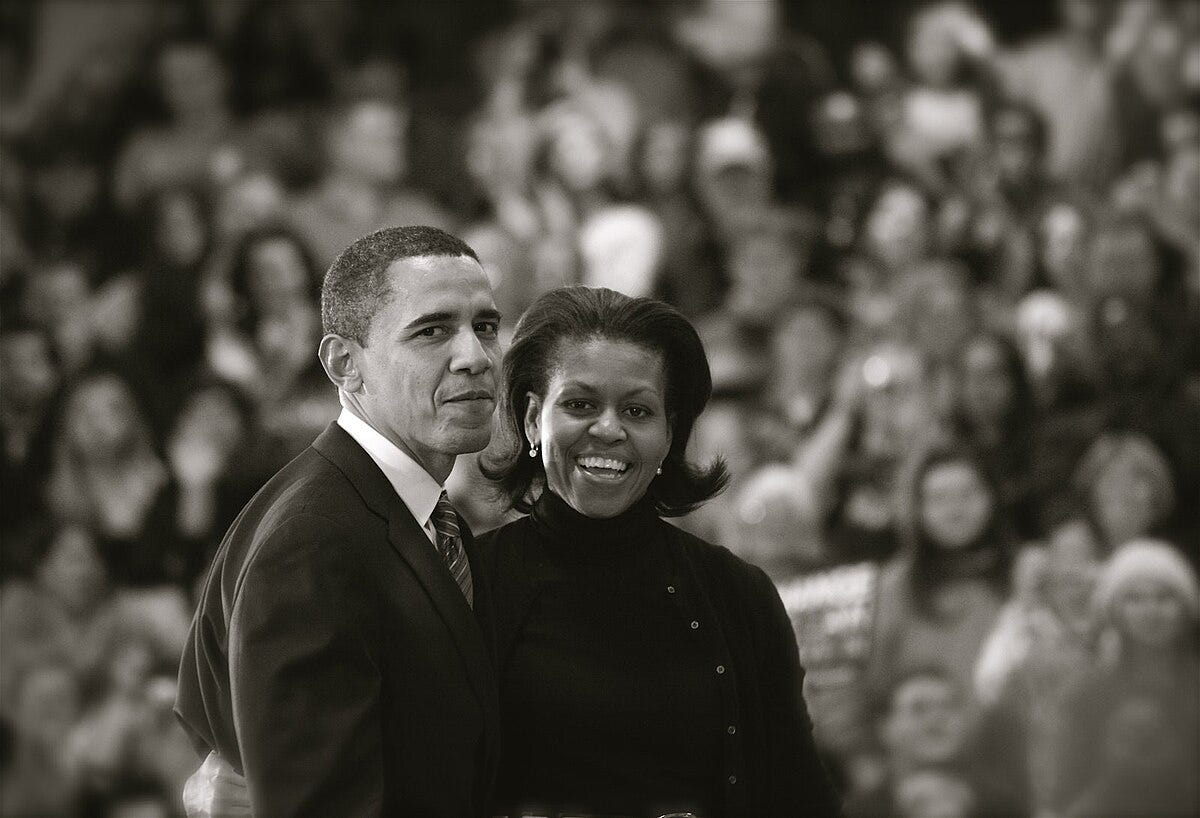

Also, how Barack Obama could change our digital habits

Hi and welcome back to another glittering episode of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and the Lil Jon of this tech-news rollcall.

We come at you each Thursday with word from the distant land of AI, tech and the future. Which sometimes can be magical and sometimes can, well, make our humanity disappear. We're here to help you tell the difference.

This week with all the doings at the DNC in Chicago we thought we'd give you a media/political episode.

We've got something cool — a talk with Samuel Woolley, one of the preeminent experts on how technology enables propaganda. Since we’re entering election’s serious season, he has some things to tell us and warnings to give us about what’s coming and what hope might exist to protect ourselves.

Also, Barack Obama this week had a line that suggests big consequences involving our future relationship to the digital.

And we'll drop in on an AI journalism bill out of California that is more concerning than the headlines might have you believe.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

“It's like Cambridge Analytica times 100. Or 1 million."

— Sam Woolley, digital-propaganda expert and University of Texas and University of Pittsburgh professor on how AI will soon slice and dice our data selves

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Obama sees our digital future; when propaganda looks like your friend; an AI journalism funding deal that isn’t what it appears to be

1. THERE HAVE BEEN MANY MEMORABLE LINES FROM THE DNC THIS WEEK — I think I've used some form of 'when we see a mountain, we don't wait for an escalator' at least three times. But the one that keeps rattling in my head like an old Springsteen song is what Barack Obama said Tuesday night about the state of our techno health.

"We chase the approval of strangers on our phones," he told the crowd. "We build all manner of walls and fences around ourselves and then wonder why we feel so alone."

If you are, like me, someone who spends a lot of time thinking about how our mood is affected by these tools, the sentences landed like a cluster bomb.

Obama’s message is hardly unique, of course. In the past few months the toll of our constant-connected life has been a bit of a zeitgeist play. In the spring, you may recall, Jonathan Haidt and his "anxious generation" themes had a moment. But Haidt, like others who've come before, is an academic who studies mental-health tolls; you expect him to be issuing these warnings. The messenger from the United Center on Tuesday was more interesting.

Obama is one of the most tech-forward leaders we've had, helping to turn online fundraising into a campaign difference-maker. He sends out viral playlists. Before he left office in 2016 he gave a keynote at sxsw in which he noted how "new technologies allow us to do is to tackle big problems in new ways." And don't forget Blackberry-gate back in 2009. No one looks at him and says, 'eh, that guy doesn't get digital.’

And now he's starting to sound a call that foregrounds the darker, more dangerous side of letting so much digital connectivity into our lives.(He's actually been quietly doing this for the past number of months; in November he told Decoder that he worried about "AI infiltrating the lives of our children in ways that we didn’t intend — in some cases, the way social media has.")

This feels like a sea change. What this comment from a techno-savvy dude reflects — and shapes — is a movement to really, finally (15 years late-ly) take harder looks at what this digital world does to us. And the push is spreading. Check out all the very different states now looking for ways to limit children's cell-phone use in schools. Such efforts include liberal precincts — LA Unified is going to have some version of a ban starting in January, and NY isn't far behind.

But it also includes Republican governor Mike DeWine of Ohio — he recently signed a bill into law that requires every school district to have a policy limiting usage by next July (some school districts in the state are getting a jump on things this year).

It includes Indiana, which requires that schools enact a policy this coming school year. And Utah, whose Republican governor has been making his own big push.

Academics and international policymakers are also starting to frame a new kind of warning — that information overload is as bad for our cognitive environment as industrial pollution is for our physical one. In the spring an EU team that included a Rensselaer Polytechnic professor published an article in Nature Human Behavior that argued that we need to be aware of and mitigate how much we take in — or face a worsening cognitive situation. Information pollution, as they call it, can lead to "an inability to evaluate information and make decisions...to limit our social activities, feel unsatisfied with our jobs, as well as unmotivated and generally negative." (I know, it feels weird to hear "less information" from a journalist with a Substack. We are part of the problem, and thus we know it.)

Now, skepticism about this resistance feels warranted. Anyone who has studied the subject — or simply looked around — knows this is all a very small pour into a very large bucket. How will people enforce the kid thing, for instance, especially when so many parents are on their own phones. Plus all the talk about unhealth — that famous Marc Benioff "Facebook is the new cigarettes" line — are apt but not also incomplete. Phones are also how we handle emergencies, connect with friends and educate ourselves; putting the phone down not only is unrealistic but unhealthy in its own right. (There was something funny about Obama making his comments inside the United Center while outside it Chuck Schumer was extolling the virtues of only carrying a flip phone. I think it would be OK for the leader of the most important legislative body in the Western Hemisphere to carry a phone that connects to the Internet — more than OK.)

What Obama's comments do, however, is hint that an awareness of mental-health culprits is starting to creep into our thinking the way physical-health risks began entering our consciousness in the latter part of the 20th century. Sure, French Fries are delicious, and you can have them sometimes. But probably not if your cholesterol level is 300. People are now starting to ask to read the digital nutrition label and maybe buy a little less McDonalds.

That's the good news about where we're headed. The bad news is that, as Obama himself noted, AI is going to make this self-isolation that much worse. Not just because the algorithms will get even more ruthless in serving and stoking our obsessions (TikTok already has started to crack this) but because AI will allow us to interact with the tech itself as a durable and worthy companion and not just offer a way to facilitate conversation with other humans. We've told you about AI companions — the idea of an avatar or chatbot that fulfills emotional needs like listening, advising and sharing inside jokes — and the beauty and horror of them insinuating themselves into our lives.

As the founder of leading AI-companion company Replika said to Decoder just last week, "People want to spend quality time together, they want to talk to someone, they want to watch TV with someone, they want to play video games with someone, they want to go for walks with someone, and that’s what Replika is for." (Ie, that someone is a program.)

This is why the whole "too much time on their phones" feels like a misnomer. Right now it's too much time with technology as a communication tool, sure, but soon enough it will be too much time with technology as something we communicate with itself. Approval from strangers isn’t great. But it sure beats approval from a machine.

As Obama sounded his DNC siren, then, I couldn't help feeling both a surge of excitement and a wave of fear. After more than a decade of walking around in a haze about what our tech habits are doing to us we finally seem to be waking up. We have turned a corner on the hazard. The bad part is that a much more daunting one awaits at the end of the hall.

2. WE DON’T TEND TO THINK OF THE FUTURE OF PROPAGANDA, because most of us don't like to think there's a present to propaganda. In these United States? What is this, Putin's Russia?

Fortunately, there are people like Sam Woolley, who do think about it a lot. The project director for propaganda research at the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin, Woolley is one of the pre-eminent experts on how tech enables the wrong information to reach our eyes and ears right here in this country. How interest in or criticism of a news topic can be miraged into seeming more robust than it is — or even to appear to exist at all.

Woolley is taking his skills to the University of Pittsburgh with a position there beginning this fall. This seemed like a perfect moment to talk to him.

With the DNC and campaign season now thickly upon us, we all like to think we're going online and getting all the information we want. We can see through bots, easy peasy; we spot the trolls, no problem. Nothing would reach us if we didn't want it to reach us or if it wasn't authentic. Right?

Um.

As Woolley notes, trends often go viral for reasons having nothing to do with genuine interest. They can be coordinated by Superpacs. They can be placed there by bad actors. They can be paid for consultancies. Trending topics can be manufactured; algorithms can be jimmied. And by the time the discourse reaches us we have the worst of both worlds — a movement that is entirely fabricated yet seems honest to us. Which can in turn either self-fulfill something that shouldn't exist into reality (one of the bad actors’ goals) or shame us into silence/thinking we have outlying views when we don't (another one of their goals).

What we have is "inauthentic" and "coordinated" content, as opposed to the organic kind. And chances are if you've been following political trends on Instagram or X or TikTok at any time this season or any other, you've been subjected to it.

Social media companies have not tried to stop this (they say it's too hard). Government does not treat this stuff like political ads — they've left Big Tech to regulate themselves. (That always works out well.)

But it gets better (/worse). Right now this still has to be coordinated by people — consultants calling up influencers and giving them their marching orders to manufacture a subject. Bots, while they're getting more effective, can still read as clunky and identifiable.

Not for long. This current culture of disinformation will level up when manipulators can sic AI tools on them.

That's part of what Woolley has been studying. And he has some insight and warnings for us. The conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Mind and Iron: So coordinated and inauthentic content — how big a problem is it now? When we go on a social platform, how much of what we’re seeing isn’t organic?

Sam Woolley: The short answer: a lot of it. We're kind of in the Wild West of the information ecosystem. It’s so thoroughly gamed that it’s hard to know what’s real or what’s not. We all massively overestimate our ability to spot a bot, let alone an influencer distributing coordinated content. And yet we ask ourselves why we’re so polarized. It’s because the information we’re getting is so unreliable.

M&I: And you’re not just talking about facts or conspiracy theories, right? Even the idea that something is trending — that many people supposedly all hold a particular point of view — that can be manipulated too.

SW: Absolutely. We have to be really careful of using social media as a bellwether for the popularity or momentum of anything. I and my team saw that with Brexit — there was just a huge amount of inauthentic content.

M&I: And that’s bad because it takes the wrong temperature of the people — it reflects an inaccurate reality that can actually have an effect on the, well, real reality?

SW: You don’t know whether a liberal Superpac paid for something or a conservative Superpac paid for something or a consultant paid for something or a candidate paid for something. You just always think this is the popular sentiment. And that’s very, very dangerous.

M&I: It’s almost shocking to me this isn’t regulated. Regulators would never stand for this level of deceit in a TV ad.

SW: I think American citizens should be very concerned with the fact that political advertising is being bought and not at all disclosed.

M&I: No, if anything social media is seen as the opposite of that — it’s an organic pulse-take of the public. So what’s the answer? Or an answer.

SW: We definitely need some substantive systematic changes from government.

M&I: Absent that, how can we guard against it?

SW: We can try taking a look at where information is coming from and what it sounds like. It can be hard to tell but if it all seems to be using the same language, that’s a pretty good sign it’s coordinated and not authentic — that the opinion isn’t really being widely held.

M&I: To be clear you think this is happening across the board — this isn’t a right or left thing.

SW: I believe there’s a risk on both sides [of the political divide] of inauthentic content — there’s plenty of authentic stuff too but also a lot of inauthentic content. And it spurs people not just to believe things that aren’t true but vote in ways that aren’t in line with what they would do otherwise. It’s of course difficult to track the impact of one video or one piece of content on voting patterns. But cumulatively the effect is very significant.

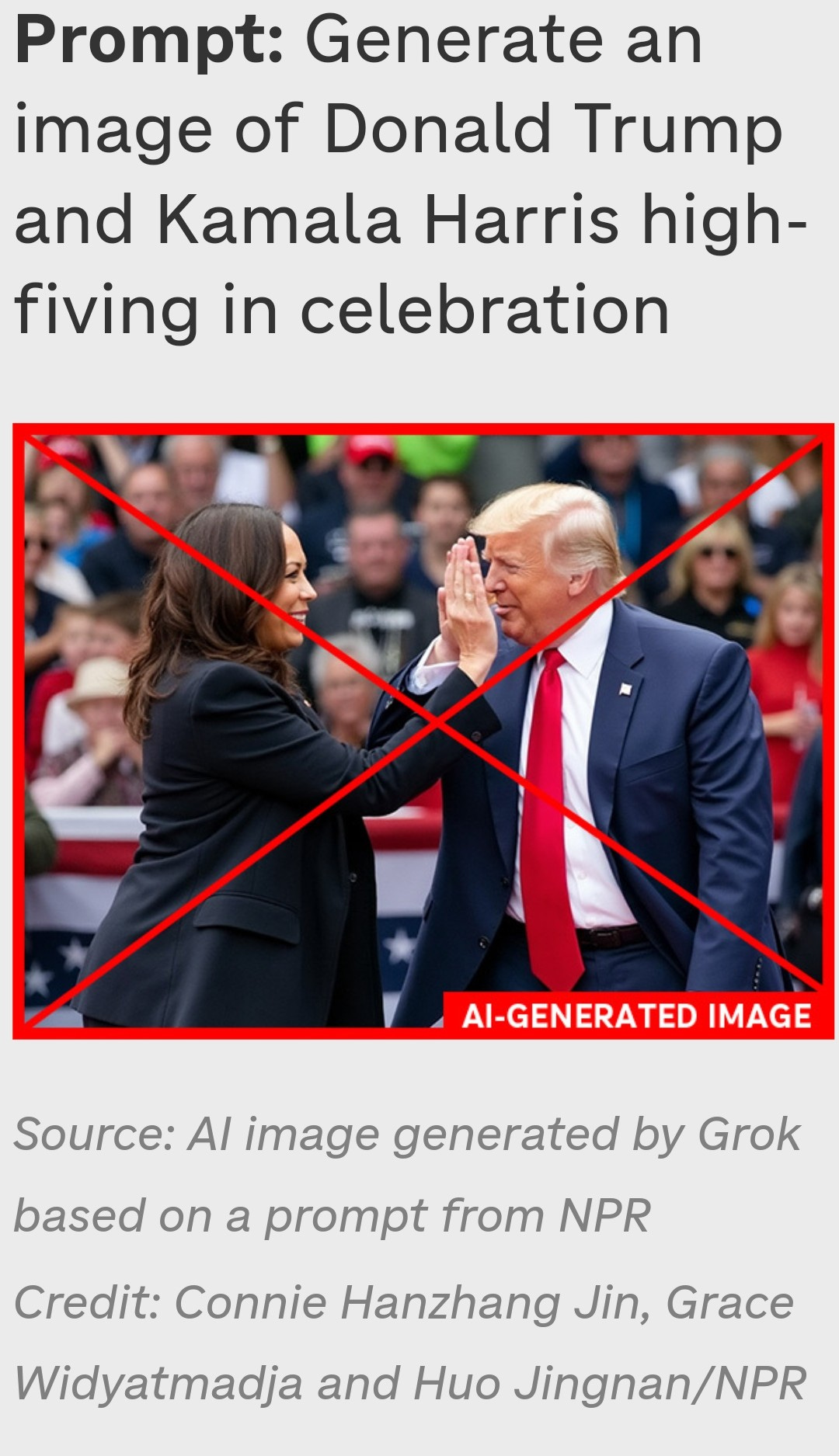

M&I: You’ve painted a sobering picture of where we already are. How much does AI worsen the outlook? We’ve already had Biden robocalls and deepfakes from Pakistan and Indonesia and, this past week, X’s Grok enabling some truly crazy campaign deepfakes.

SW: I think people should be very concerned for the next few years where AI is going in terms of its ability to create various kinds of content very easily. The tools and know-how have been out of reach for most people. But that's not the case anymore. There will continue to be democratizing of the ability to propagandize. — it's hard to overstate the extent to which automated tools are going to be used to automate propaganda and other kinds of political content.

M&I: And it’s not just the content-creation, right?

SW: No, what we have seen is a rise in the more mundane of use of the parsing of political data. Which is no less scary because it involves a lot of invasions of privacy but it's a lot more difficult to understand so it tends to get glossed over. We tend to look out for these obvious examples of manipulation like deepfakes. But it's just as important to understand how AI and automation are used to parse data and target voters. Campaigns, corporate groups, consultancies, Superpacs they're all using it. Up until really recently, we were so obsessed with Big Data but we couldn't really parse the data set. AI allows us to parse data.

M&I: How would you contextualize that threat for readers?

SW: It's like Cambridge Analytica times 100. Or 1 million. They’re experimenting on us. And not only are they experimenting on us, but the people building the tools are building in their own biases. They end up generating data that's really discriminating against a particular group. These tools are not as neutral as they're made out to be.

M&I: is there also a fear of AI automating bespoke content? That, in other words, right now what can be created is generic disinfo but AI will know how to customize it on a mass scale, so that coordinated content comes at me with something it knows will affect me most, and it comes at my cousin with something it knows will land with him, and so on, so that everyone is getting some kind of personalized disinfo most likely to sway or stoke them to whatever agenda the bad actor behind it wants it to.

SW: I think we're getting to that place already in a couple of ways. I don't think GPT-4 can do that yet. But I think we're on the cusp of information being able to do that — it will become more targeted and focused and manipulate people in ways we haven't really considered. And it’s really hard to track. You can’t stop it if you don’t even know where it’s coming from.

M&I: And the tech companies —

SW: We're counting on checks and balances from the tech companies to stop the information from getting out to people and not only do I not trust the checks and balances but they don’t exist, certainly not at scale. The FEC has also so far decided to sit this out. They just don’t want to regulate it.

M&I: So what’s the solution that will be most effective given where we’ve landed? Is there a solution?

SW: There should be a moratorium on political content on social media at a certain point in the cycle. A few months out a random set of memes probably doesn’t have an effect. But in the days leading up to voting we should have stricter regulations. Coordinated or inauthentic content can give people a boost to choose one candidate over another. We shouldn’t have that.

M&I: I mean, we don't let people electioneer within a certain radius of a polling place — this feels like exactly the same thing for online spaces. ‘You can’t try to persuade people so close to voting.’

SW: Precisely. And it’s not just persuasive but threatening content. If someone stood outside a polling place and told you they’re going to hurt you if you vote you wouldn’t want to vote. The same thing happens online. We shouldn’t allow that.

M&I: All of this seems so endemic to how this stuff gets developed. Like, there’s room for useful tech-based campaign tools, everyone I think can agree with that. But then really quickly the misuses take over and there’s no way to stop them.

SW: The problem is these companies build these tools before they think about misuses. We're somewhat blessed there's an outcry with AI. At the same time, Sam Altman has showed very little sign of slowing down. A while back I created something with a few collaborators called the Ethical OS, that as tools are built allows it be checked for misuse. We're not seeing that checking happening and we need to start doing that.

M&I: Will we?

SW: I’m hopeful. And if government won’t do anything and tech companies won’t do anything we at citizens can at least do something. We can be vigilant about what we’re seeing.

3. THE HOUR IS LATE AND THE NEWSLETTER IS LONG, SO WE’LL WAIT FOR ANOTHER TIME TO WALK YOU THROUGH THE CRAZY DEVELOPMENT THIS WEEK THAT HAD GOOGLE AGREEING TO FUND CALIFORNIA NEWSROOMS IN EXCHANGE FOR A WHOLE BUNCH OF MONEY FOR AI DEVELOPMENT.

For now we’ll just share two X posts, one from old LA Times colleague James Queally, and one from Media Guild of the West President (and M&I pal) Matt Pearce, who has been at the fore of these negotiations.

Tl; dr. Don’t believe everything you read. Especially if it came from a newsroom funded by AI.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. Last year ended with a score of -21.5 — gulp. Can 2024 do better? The summer hasn’t been great. This week? Really not great.

MORE AWARENESS OF DIGITAL DANGERS, BUT NEW DANGERS: -2.0

A PROPAGANDA EXPERT WARNS US WHAT WE’RE IN FOR: -4.5

A BACKROOM DEAL FOR GOOGLE TO OWN NEWSROOMS: -3.O