Mind and Iron: Now starring: AI Humphrey Bogart and Selena Gomez

Hang on for a wild actor ride. Also, synthetic journalism, our new frenemy. And can biotech cure sickle cell disease?

Hi and welcome back to Mind and Iron. I’m Steve Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and conductor of this funky orchestra.

Tech changes continue to bombard us, so we’re here to make sense of them — to separate out what we should fight for, run from and generally care about in this AI-enabled future.

As always, please sign up here if you’re reading this as a forward or on the Web.

And please consider pledging a subscription. Independent journalism on this topic is more important than ever. Your commitment to spend a few bucks/month on our issues will ensure it continues to flourish.

After all the OpenAI madness of the past few weeks, this Thursday we turn our attention to some changes across the media-verse. Why screen acting is about to get seriously weird — for both the actors and those of us who enjoy watching them. (Like, get-ready-for-Humphrey-Bogart-in-some-new-releases weird.) Also why the recent Sports Illustrated AI-journalism scandal may only be the beginning of news stories that are less than human. And a biotech discovery that might — good news! — cure a disease that afflicts 100,000 Americans and 20 million people worldwide.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

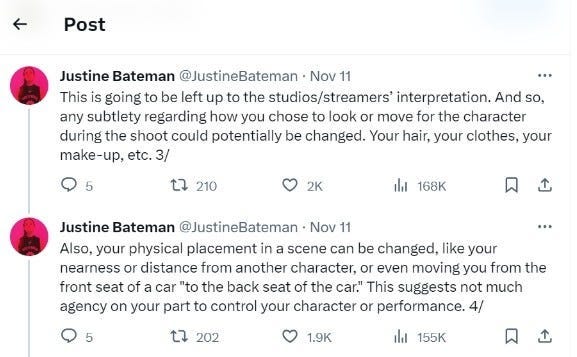

“We are in for a very unpleasant era for actors and crew."

—Hollywood fixture and anti-AI activist Justine Bateman, understating her worries about the coming period of automated art

Let’s get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Acting goes synthetic; Sports Illustrated’s very terrible horrible no good AI day; is gene-editing about to cure sickle cell disease?

1. ON TUESDAY MORE THAN 60,000 MEMBERS OF THE SCREEN ACTORS GUILD agreed — with some holdouts — to ratify the new contract their leaders negotiated. They did so despite uncommonly significant pushback (usually these are rubber-stamp deals) over the contract’s AI clauses. Justine Bateman — who as we've noted has been a major and often justified skeptic — was among the deal’s key protestors.

The guild’s national board had encouraged a yes vote, although 14 percent of that group resisted the call. (National board member Matthew Modine called the provisions “purposefully vague and demands union members to release their autonomy.”)

The main issue centered on “consent and compensation” — whether actors will need to give permission and subsequently get paid when studios use their AI scans in future entertainment. Essentially, it’s about who gets to control the digital spawn of our physical human work.

When the proposed agreement was announced a month ago we still didn’t know exactly what it said. Now we do, and it’s a mixed bag.

Some consent and compensation requirements are built into the deal. But not fully. Bateman noted her own feelings about the shortcomings. "You could find yourself in a project you never consented to...you’ll be used like a type of rag doll in post-production...Bottomline, we are in for a very unpleasant era for actors and crew."

She has a long list of concerns. Some are more worrisome; some less. I wanted to focus on two that I think could impact employees across many industries. (The whole thread is worth reading though.)

The first is what happens when small details in a performance are changed using AI. As she puts it:

Actors always cede control of their performance to directors; after all, they’re not in the edit room. And facial expressions and small details are regularly changed. The good filmmakers simply find a way to keep their actors happy.

But we’re entering a new era — AI makes these changes SO much easier. How an actor on set was moving, speaking, making facial expressions — all will now be fungible, changed with the swipe of a screen.

That’s good news for studios and (maybe) directors. But it’s a nightmare for actors, who do not make these choices lightly in the first place. If they are to be represented as making different choices, it would be nice if they were present, never mind actually signing off. And nothing in this agreement seems to require that they do.

This phenomenon won’t be limited to Hollywood. Digital enhancements (read: revisions) of all of our labor are going to become more common for the simple reason that it will be a lot easier for our bosses to make them. Whether we’re in law, medicine, media, marketing, design, science, education or any of a dozen other professions, the risk that the people we work for can come in and use AI to meddle with —er, “enhance” — our work is real. And while the good employers will collaborate with their employees, plenty of bad ones — or simply clueless ones — won’t.

As the Substacker Explainable AI recently wrote, “the world is populated with many awful executives bent on using AI to make [an employee’s] creative job even more difficult.” Flashpoints will abound. And if the SAG agreement is any signpost, formal protections will be non-existent.

It’s every employee for themselves when it comes to making sure they’re not superseded by a nettlesome boss with easy access to a GPT. And Bateman is right to say we should wake up and start paying attention. Mass automation and layoffs is not the only way this tech can make our lives miserable.

The second concern is what happens when an employee pushes back on AI. That is, even when protections are in place, will the people most uncomfortable with AI find themselves at a disadvantage because others will be less resistant? Here’s the issue as it plays out for the actors.

The technical details of the AI scan in question are a bit beside the point. (It’s a scan made outside the confines of a film shoot, like what Jason Reitman did to get Harold Ramis back in “Ghostbusters: Afterlife.”) What is relevant is that, for certain types of scans, there’s no baseline for what studios must pay actors. And that means — since contracts are all about leverage — that those willing to take less will be at an advantage.

For that matter, actors/independent contractors who are willing to give consent without preconditions will also have the edge in landing jobs; why would a studio hire someone making a fuss over AI when the next person on their call sheet is handing over rights no problem? Actors aren’t just going to be competing against digital creations for work — they’ll also be competing against other actors who are more laissez-faire about digital creations.

What is being described here, in other words, is a de facto digital takeover of human agency. A backdoor, if you will. Companies don’t need to legally mandate they can take all rights to AI re-creations of our work — they can simply find people willing to give them up and pressure us that way. “You’re under no obligation to allow us to use AI on you — but did we mention that five rival job candidates would? But again, totally up to you.” You see where this goes sans union or legal protections.

(My anecdotal sense is even many of the actors who voted yes are worried about this — they just don't have the stomach to stay on strike and/or hope many of these issues won't reach full flower before negotiations come up on the next contract in 2.5 years).

But just focusing on the workforce concerns, important as they are, misses the other part of the question. Unspoken in these changes to entertainment production is a change to the entertainment itself. This is about results as much as process.

Because I don’t think we’ve even begun to grasp how much this will change the film and television we watch.

For starters, certain actors could become virtually ubiquitous; it’s a lot easier to double-book if you don’t actually have to show up to a set.

New talent could also be stymied in the pipeline. If you think Hollywood’s current reboot culture puts a cap on new ideas, just wait until they can reboot actors.

And then there’s the general vibe of Bateman’s argument — that art is going to get a lot less human. For many years screen entertainment has existed in a kind of detente with technology; whether it’s digital effects in a big-budget action movie or the emergence of CG animated movies, the human artist has been in a low-key wrestle with the digital tool (and, yes, the people who operate it). Now this could become a full-on hot war. With actors — at least live ones who do live things on a set — relegated to a band of ragtag Katniss-y fighters in the Arena.

Simply put, watching actual people giving expression to other actual people on a screen could become an endangered practice.

[A Cannes movie from the Israeli director Ari Folman, "The Congress," contemplated this some years ago. This is how I described its plot in the LA Times…in 2013:

“The film begins with Robin Wright, playing a version of herself named Robin Wright, facing a stark choice from her agent (Harvey Keitel). Approaching her mid-40s, the top roles aren’t coming her way anymore. So an oily studio executive has a proposal: he wants to record all of Wright’s expressions and use them in digitally manipulated roles, in everything from romantic comedies to pulp thrillers. If Wright signs on, she’ll be given a lot of money and basically be turned into a movie star in perpetuity.

There’s only one catch: she’ll never be allowed to act again.”]

But for all the reasons to fall into dyspepsia, I think we should keep an open mind to some of the cooler possibilities. And they do exist. One simple scenario: actors across different eras playing opposite each other. If you thought it was fun when Natalie Cole sang a duet with her late father Nat King Cole, just imagine when Golden Age stars begin mixing with Robert Downey and Viola Davis.

Seeing, say, Humphrey Bogart act opposite Selena Gomez will be a novelty — but also an opportunity for the right director to unite them in fascinating ways. What sounds like a crass experiment in intergenerational marketing can actually be the start of a newly pliant medium in which we are no longer limited to seeing new work only from the artists in whose generation we happen to live — nor is talent limited to playing alongside their contemporaries. This could be the beginning of some beautiful friendships.

I know, you’re skeptical. I am too. I suspect when we get bad stuff it will be truly bad — even "Howard the Duck" never had to contend with an actor from the Silent Era crashing through his window. But when we get something good, it might well be new and original in ways we never thought possible.

Tl;dr, I don't think we should be so credulous to believe the studios will always or even often use this tool responsibly. But I don't think we should be so cynical to believe some artists won't find ways to make magic with it either. Because in this coming era the whole gamut — the great, the awful and the simply weird — will be technically possible.

Actors just gave studios a cautious greenlight on AI. Let’s see where they drive with it.

2. AS WE COVERED ALL THE OPENAI HIJINKS OVER THE PAST TWO WEEKS, WE NEGLECTED SOME IMPORTANT STORIES PERCOLATING OUTSIDE THE TOWN OF ALTMANVILLE.

One of them involved Sports Illustrated's alleged use of AI to generate articles on its site. You may have heard about his one — The Arena Group, the decidedly dicey and non-journalistic parent company of the title, brought on a firm that may have used a decidedly dicey and non-journalistic tactic to generate stories.

As an article in Futurism alleged, the SI site was running bare-bones product reviews that were seemingly written by machines, and even attached fake headshots and bylines to make them seem real, all without disclosing any of it.

Arena rather unpersuasively denied that these articles were written by AI, saying they came from real people who asked to remain anonymous. As company reps explained it, they used AdVon Commerce, a sponsored-content firm, for some product reviews and the firm went out and did…whatever it is they did.

The outrage after Futurism revealed the gambit was deep and wide — this managed to offend both journalists AND technologists. The stories weren’t good, suggesting computer codes didn’t get what journalists did. And the computer codes weren’t good, suggesting that the company that ran them didn’t understand what coders did. Also, there were some true howlers, like one author thumbnail seeming to come from a site selling AI headshots of a "neutral white young-adult male.” It’s not only a shady AI product — it’s also the world’s worst band name.

More backtracking followed, and SI went out and took down the stories and said it was ending the AdVon partnership. Soon after a few top SI execs were let go. The man whose company owns a controlling stake in Arena held a call with SI execs Wednesday in which he told them to “stop doing dumb stuff.” It’s safe to say we won’t be seeing machines writing any more Sports Illustrated pieces anytime soon.

AI and journalism have been in an awkward dance for a while now; every time someone tries these experiments, egg ends up all over their lede. Gannett was unable even to manage basic high-school game items when it tried a partnership with a company called LedeAI this summer. The pieces used cringe language like “thin win” and "close encounter of the athletic kind" and prompted a columnist for The Athletic to quip "I feel like I was there!"

But as much as those of us who follow (and, um, write for) media like to laugh at these examples — and some of them are hilarious — I can’t help feeling like we’re committing a sin of pride. We’re a little like the naive henchman in a crime comedy chuckling at the hero’s misfortune just before a piano falls on his head. It wasn’t too long ago when the idea of writing essentially coherent letters seemed well out of AI’s reach, and now look where we are.

Sure, a lot of reporting indeed requires old-fashioned shoe-leather work — as Gay Talese pungently noted to me when I had GPT-3 write a version of his landmark “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” there’s no AI that can replace reporting — “The technology is ‘you have to be there.’” Fair enough. But in the coming years that will look less and less true for simple aggregation and news writing. And copy editing, layout and other tasks that require less soul and more a kind of high-level programming (that’s how all of us learned, after all).

Faster microprocessors and better machine training will get us there soon enough, and then the only factor holding back media bosses from employing them will be shame and stigma. And that tends to fade when a few zeros come off the bottom line.

The reality is that journalism has a history of streamlining jobs that once seemed fundamental, and if you don’t believe me ask your local typesetter or copy boy.

So I wonder if maybe the reaction I and my colleagues have to this should be less eyerolling the latest clunky attempt to automate writing and more thinking about what we want the world to look like when the attempts get less clunky. Media executives will look to swap out humans as soon as they can; how do we feel about what comes next?

While I think some guardrails are called for — we shouldn’t accept machines committing even a slightly higher rate of errors or bad prose — I’m not sure we should be quaking about the end of media either. In fact, the quality of journalism may actually bump up because of these changes.

If basic wire copy can be written by a machine, that could well leave human journalists to focus on higher-quality writing and reporting. In other words, news automation won’t so much elevate machines as demote the importance of these kinds of pieces. Let’s face it — too much of the online-media landscape now is clickbaity content farms or its slightly-less-disheveled cousin, the recent college grad cutting and pasting at astronomical rates. Would the media world be worse off if some of that was farmed off to computers, leaving journalists both young and old to focus on the more skilled tasks of reporting and upscale writing?

The idea that machinizing lower-end jobs will refocus an economy on more ennobled work is a closely held belief of the automation utopians, I realize, and much debated. In this case, for instance, media outlets could simply decide to cut those people, not refocus them. Or redeploy them to TikTok. Anyone who reads this space regularly knows I’m far from a utopian about these issues.

But I also have a hard time getting too pessimistic about what these news-automation programs will do to the quality of our media. Nothing about the last 60 years of American journalism suggests writing will become more dry and mechanical. If part of the problem with AI is that it lacks soul, well, great — it can work on the writing that doesn’t require that and leave the humans to focus on that which does.

The truth is as much as the Sports Illustrated example is laughable, real change is coming. I’m just not sure it’s all bad.

[Futurism, CNN, PBS and Axios]

3. SICKLE CELL DISEASE AFFLICTS 100,000 AMERICANS, THE OVERWHELMING MAJORITY BLACK AND LATINO. IT’S A DEBILITATING CONDITION THAT DESTROYS QUALITY OF LIFE AND DECADES OF ACTUAL LIFE.

AND NOW A CUTTING-EDGE TECH TREATMENT MAY BE ABLE TO HELP ELIMINATE IT.

The FDA this week is expected to approve the technique, which makes use of CRISPR. It would be the first time that the ballyhooed gene-editing tech would be approved for use on genetic diseases. The implications, both for sickle cell patients and entire populations of people with other genetic diseases, are massive and worth mentioning.

The technique here is not simple — it basically edits sickle cell disease, which manifests as misshapen red blood cells, out of a person’s genes. CRISPR treats our gene sequence like a movie editor in 1971 did a piece of analog film, snipping and splicing until it gets the result it wants. For the sickle cell patient themselves, this can mean something far more grueling: extracting stem cells from bone marrow, chemotherapy and blood transfusions.

But if a person makes it through, the treatment holds the promise of essentially curing them of sickle cell disease — freeing them for good from the intense pain crises that come in unpredictable waves, the frequent blood transfusions, the risk of organ failure, and everything else that makes a conventional life for people who suffer from the condition nearly impossible. It would also not only vastly improve life but extend it — people with sickle cell also live 10-20 years fewer than those without it.

The curative technique, called Exa-cel, is being pioneered by a Boston biotech company named Vertex along with CRISPR Therapeutics. The firms said they found the treatment safe and effective in 29 out of 30 patients over a period of 18 months. Testimonies from people who have been involved a trial have been trickling in via the likes of MIT’s Tech Review and NPR.

An advisory committee in October said it saw few concerns with the therapy, and the FDA is expected to approve it by tomorrow. (Because this is a whole new approach, the group has said it’s being a little more vigilant.)

The FDA’s blessing would be a complex moral in addition to medical act — sickle cell disease has been a vastly undertreated and understudied disease compared even to similar conditions, and it hardly takes a leap of the imagination to understand the racist and classist behaviors that enabled that. Even with CRISPR, the incredibly high cost of the treatment (as much as $2 million per person) raises fraught questions about access.

But this treatment also is a story of hope, of people left abandoned by the conventional medical system now being saved by the cutting-edge one — a technological redress that, while it can’t begin to make up for past crimes, can perhaps start to reassure they won’t happen as much in the future. Or at least so we can wish.

The medical path isn’t clear either. There remain many unknowns about using gene-editing to cure disease. Among the FDA’s biggest concerns is edits that miss the mark slightly and potentially cause long-term health issues. (And that’s with gene-editing that happens in controlled clinical settings for diseased adults; more elective procedures involving babies is a whole other story.)

A study last year by doctors at Boston Children’s Hospital also showed that using gene-editing for disease can exacerbate the movement of DNA sequences within the genome, potentially increasing the risk for cancer.

“Genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 holds great promise for the treatment of human genetic diseases,” the authors wrote in Nature. But “unwanted outcomes…are a potential threat even if occurring in a small fraction of the edited cell population.” All technology is about the quest to make life better, and weighing the costs of what happens when we do. This takes that tension to a whole new level.

The idea of editing DNA — messing with material inside us that for millions of years has gone untouched — can only come with unknowns, and anyone who tells you otherwise is either naive or selling you something.

To think about us living through a time of fundamental advances to the codes of life itself is unspeakably exciting — and filled with risks we can’t even begin to articulate. But for 100,000 suffering Americans and 20 million other people worldwide, this now means a glimmer of hope. Something that hasn’t happened for a long time either.

[Tech Review, Nature and NPR]

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way.

Here’s how the future looks this week:

AI ACTORS ARE ON THE WAY: Cool but scary. -2

JOURNALISM COULD SOON OUTSOURCE THE LOWER-SKILL STUFF ALLOWING A FOCUS ON THE HIGHER-END REPORTING: Tentatively hopeful. +1.5

CRISPR COULD SAVE THE LIVES OF SICKLE CELL PATIENTS: Hell yeah. +4