Mind and Iron: So which jobs are safe from AI and which are toast?

Our guide to self-protection. Also, an iPhone for AI is on its way

Hi and welcome back to another fine if slightly apocalyptic episode of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, senior editor of tech and politics at The Hollywood Reporter and lead telescope operator of this newsy observatory.

Every Thursday we come at you with a vision of the future as imagined by its biggest designers, cross-referencing it with a vision of the future that we may actually want to live in. Please consider joining our community here.

This week we've got a doozy of a tale for you. We're going to kick it off with a look at the labor question — at the jobs AI will nudge us out of. Normally we don't like getting too alarmist here at M&I HQ — there are concerns about the coming realities, and we deal with them soberly and thoughtfully, or try to. But in an interview this week that was jaw-dropping even for those of us who spend our days in this toil, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei offered up to Axios a truly chilling vision of where we're headed on the labor front — and not ten years from now or five years from now but in literally the next 12-18 months.

By next Memorial Day, tens of thousands of people will be AI-ed out of a job, Amodei believes.

The piece was headlined "Behind the Curtain: A white-collar bloodbath" and I dare say that was underselling the piece. Amodei didn't just say the quiet part out loud — he climbed a Swiss mountain and began yodeling it across the canyons.

We'll get into his view, what we're looking at and offer thoughts on the jobs at most immediate risk, because it's starting to become clear what they are.

Then, a quick take on the news from the end of last week about the man who created the iPhone getting hired (for $6.5 billion) by OpenAI to create an AI device in Altmanland. I riffed on it in THR, and will share some of those thoughts here.

And finally, the return of summer fiction! Because when the world is this apocalyptic, you need a little escapist short-story break. This issue we'll be surfacing a story from last year about a grieving woman and her hologrammic reprieve, and it's at least a little more hopeful than the jobquake outlined earlier (a low bar but still). With some new stories to come in the weeks ahead.

Quick note that we'll be taking a housekeeping break next week, back at you the following Thursday with all the future news you need to arm yourself against…everything.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

“We as the producers of this technology have a duty and an obligation to be honest about what is coming… Cancer is cured, the economy grows at 10% a year, the budget is balanced — and 20% of people don't have jobs."

—Dario Amodei, CEO of AI company Anthropic, on the economic hurricane that he can see on his Doppler

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Which jobs is AI about to come for?; Carrying around an AI device; Finding peace in holograms of the departed

1. LET'S START THIS ITEM NOT WITH AMODEI'S COMMENTS BUT WITH THAT OF THE AUTHORS, Axios staples Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen, because they cut to the quick of what we're facing, job displacement-wise.

"Far too many workers still see chatbots mainly as a fancy search engine, a tireless researcher or a brilliant proofreader. Pay attention to what they actually can do: They're fantastic at summarizing, brainstorming, reading documents, reviewing legal contracts, and delivering specific (and eerily accurate) interpretations of medical symptoms and health records," they note.

Now let's not get into the ways AI can't do that, or the mistakes it makes when trying to do that. Let's just think about how company executives believe AI can do that. The executives reason — correctly or incorrectly — that humans make plenty of mistakes too, and that if margins of error are roughly comparable, wouldn't it be nice (and for public firms, even obligatory) to save money by plugging in some machine intelligence instead?

That's how the doomsday among us have been thinking about the issue of AI edging people out of jobs, particularly how journalists (the most doomsday of our species) have been thinking about it. We always suspected that was how the people who were creating these intelligences thought about it, because why else would they be investing so much energy and resources if the result didn't offer such a massive economic disruption? But these AI leaders never came out and said it, couching the changes in terms of rosy predictions of free time and human productivity and great problem-solving, as Sam Altman regularly does.

That is, until now.

Because check out the interview from Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei. His company is the more…humane OpenAI, Amodei having left that company because he thought Sam Altman’s vision was too reckless. Amodei still thinks AI, deployed responsibly, can solve a lot of the world's problems. But he's also honest: it could create a bunch of them too.

As he puts the potentialities in the interview: "Cancer is cured, the economy grows at 10% a year, the budget is balanced — and 20% of people don't have jobs."

That's actually a very glowing view, as it assumes that the machine intelligence will be so good that it will swoop in many more positive effects even with its destructive ones. And it's certainly one possibility — the ceiling on scientific breakthroughs is high, as we've noted. But what the quote also does is erroneously (and self-servingly) tie one scenario to the other. It's entirely possible that AI doesn't cure cancer but still wipes out a whole layer of entry-to-mid level jobs. You can believe Amodei's doomer comments without necessarily assuming his utopian ones.

And let's be honest about something else: Amodei has zero reason to inflate the 20 percent number. In fact if he doesn't want to be seen as society's bad guy, he probably has a few reasons to underplay it. So let's call the job losses conservatively in the 25-30 percent range. He also has zero reason to be alarmist; who wants to be the Chicken Little person, especially when they're the ones causing the sky to fall? And yet he also says this to Axios: "Most [workers] are unaware that this is about to happen. It sounds crazy, and people just don't believe it."

But when someone tells you what they're doing, believe them, to paraphrase Maya Angelou (or whoever AI tells us it is).

Steve Bannon, hardly an expert on AI, hits the bullseye with a remark he makes in the story. "I don't think anyone is taking into consideration how administrative, managerial and tech jobs for people under 30 — entry-level jobs that are so important in your 20s — are going to be eviscerated."

Gen X was the first generation in postwar America to worry (rightly) they'd do worse than their parents. But those Pearl Jam-y handwringers lived in nirvana compared to what's coming. Because if this blow-up-the-out-side-world scenario is true and so, so many of the lost jobs are going to be weighted towards recent college graduates, what will that mean for a generation of people that needs not just money but on-the-job training; what will it mean for companies whose next generation of talent needs to learn at the feet of its veterans; and most important what will it mean for all the parents that generation will now be moving in with?

Seriously, that last one is a legit socioeconomic question, one that we have zero answers for. Already one in three people in America between the ages of 18 and 34 live with their parents, in a trend that's been spiking since 2005 but will seem downright mild compared to what happens when all the jobs that the other two-thirds have relied on not to live with their parents up and vanish. The level of societal reordering we're looking at here is stunning if you stop and think about it.

And it would be delulu to think this is just a young person's problem. The Axios piece cites Mark Zuckerberg's comments to Joe Rogan from earlier this year that a whole class of pretty highly skilled jobs are about to be gone. "Probably in 2025, we at Meta, as well as the other companies that are basically working on this, are going to have an AI that can effectively be a sort of mid-level engineer that you have at your company that can write code." Btw, there are 340,000 people doing coding jobs in the U.S. Also btw, those ranks have already come down from 450,000 since 2023, in part because of AI. And that's just one profession.

As Axios says of experts’ belief: "Few doubt [the shift] is coming fast. The common consensus: It'll hit gradually and then suddenly, perhaps next year."

A pair of AI ripoff incidents this week already illustrate the problem. Sky News has an infuriating tale of the Scottish rail system just outright cribbing the voice of a noted voice actor for their ad campaign — without telling let alone paying her. And Wired reports on a noted YouTube gamer who's seen the same thing happen to him on a bunch of Doom videos.

These are skilled people — someone who built a following as an influencer and someone who honed her craft as a voice actor. These are not jobs anyone with a little time on their hands can simply do. And AI swooped right in and took them, with, at least for the moment, little consequence and not really much clear legal recourse.

All of which leads to the question we're all thinking. What is my job’s level of risk? The conventional thinking in AI-displacement circles is that "laptop" jobs are most vulnerable — the millions of accountants, journalists, graphic designers, academics, publicists, engineers, researchers, social-media experts, ad executives, tech professionals, data scientists, non-trial lawyers, marketers and other people whose roles are heavily carried out via keyboard and screen.

That's true, but it doesn't mean others are safe (and it doesn't mean there aren’t ways even people in those professions can AI-proof).

The simple principle is that the more your job requires an on-site person-to-person relational component, the safer you'll be, because that's something an AI can't easily do. The more your job entails a level of geography-less abstract thinking, the more at risk you'll be. (On the first score btw I don't mean jobs where your employer makes you come in when you don't have to, creating the illusion of an on-site component — I mean jobs where you physically need to be there, existentially.)

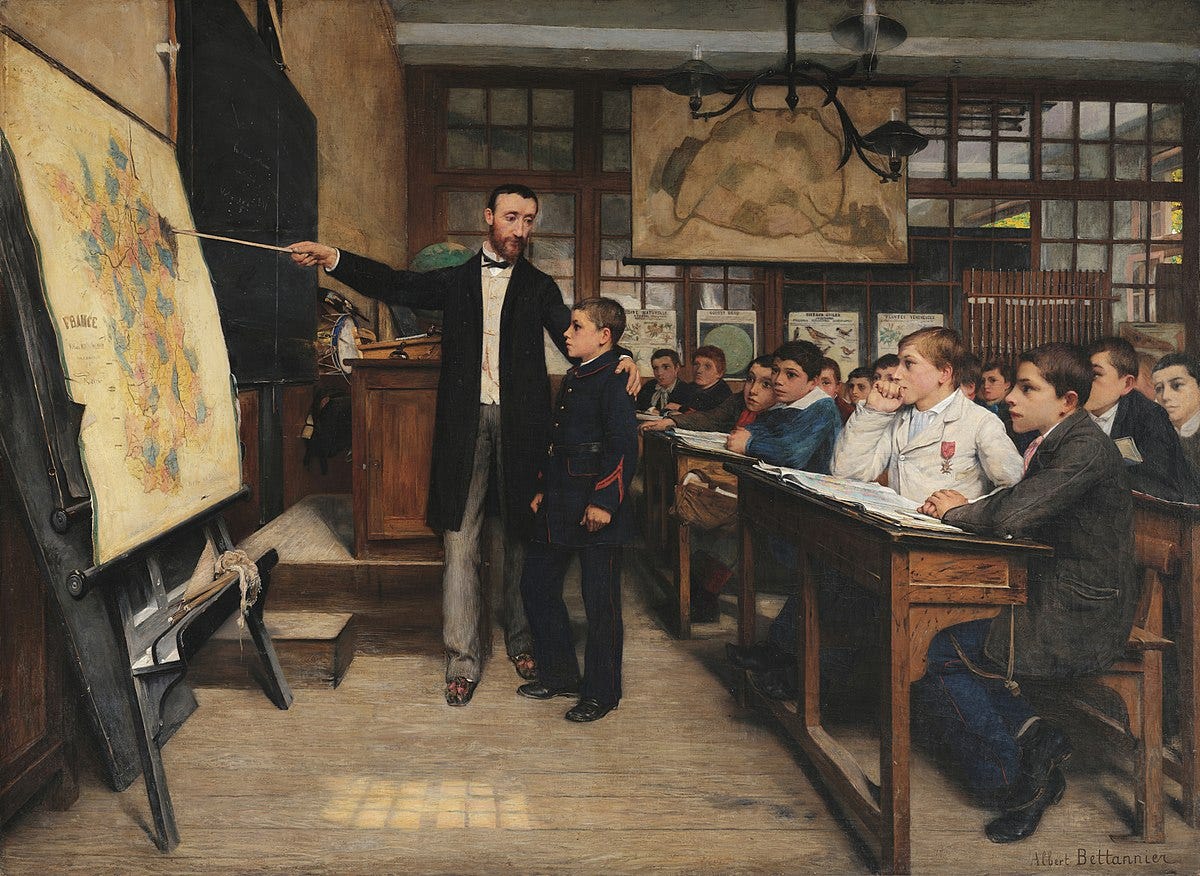

So that puts nursing, teaching, in-person sales, lobbying, the clergy and other fields with a high level of interpersonal interaction/massaging/schmoozing/caretaking in a much better position. AI can nibble at these edges — one imagines a high-level doctor's office will be scaled back if recordkeeping and symptom-gathering tasks can be automated, for instance — but it doesn't strike at the heart of these jobs, which involves a high level of the interpersonal.

Contrast that with all those laptop jobs, where you can be anywhere and do it well — where you're paid for thinking more than talking or interacting — and the chasm is evident. Clearly it'll start at the bottom — if you're a paralegal who's summarizing cases you're a lot more vulnerable than a top-flight attorney who's prepping an opening-argument in court; that's where Bannon and his entry-level take is accurate. But as these models improve, the evaporation will work its way up.

You might find a bitter irony here in these laptop professions getting their karmic due; after all, these are jobs that got away with a relative lack of interruption during the pandemic, and continue to give workers a level of cushiness compared to those who have to take two buses at 5 am every day. These are the jobs that were supposed to be desirable, inhabited by all those sharp-dressed MacBook Air-toters in airport lounges and high-end cafes. And now the tables have turned on them. But the truth is there should be no moral schadenfreude here. Losing this many jobs is bad for everyone.

There's a further twist, and it's even more...troubling. Even if you have one of the in-person physical jobs, it can be at risk if it's part of an industry that's displaced by AI. Take Hollywood, the realm I've covered for large stretches of my career. If you're a craft-services or makeup person you might think you're safe — an AI isn't cooking or applying a smokey eye. BUT AI production could drastically reduce the number of physical sets overall — who needs them when you can create so much in-model? And once you eliminate physical sets, all those physical jobs go with them.

But here's a little bit of good news — there is something we can do. Even people with those abstract think-y jobs can find ways out of the dilemma by doubling down on the parts of their job an AI struggles with or doesn't even attempt. If you're in advertising you're better off drumming up new business and dealing with clients than designing campaigns. If you're in academia get out of research and into teaching. If you're in mental health sidestep administration and move into in-person therapy (we're going to need a lot of that). If you're in politics you're better off building relationships than generating briefings. Etc.

In my own line of work, reporting and source-building is the kind of thing technology can't really do. As AI gobbles up from the bottom like some kind of Stephen King monster, journalists can avoid its hungry teeth in two ways: by getting so good at the writing part an LLM can't touch you (but do you really want to get into a footrace with AI?) or hopping off that vine onto one it's not even climbing, like in-person or real-time reporting.

In short, think of the part of your job a very advanced computer could never do, and lean into that. Leave the rest behind.

The picture isn't pretty. But it does offer some ways out. And it sure as hell beats living with your parents.

2. WILL THIS AI-INTEGRATED WORLD WE ARE HEADED FOR MEAN CARRYING AROUND OUR USUAL IPHONE TO TALK TO US? Or maybe a new, as-yet developed AI device?

The latter, if Altman and his $6.5 billion action means anything. That’s how much Altman paid to bring aboard iPhone/iPod designer Jony Ive and his company io to OpenAI (OpenAIo?). What will Ive design? Nobody knows, and this video meant to shed light managed to confuse us more. Some kind of “family of products,” which will presumably take Ive’s talent for little machines we like to carry as accessories and bring them together with those massive models that OpenAI hopes will serve as our AI Agents.

The result of the combined company will be “focused on developing products that inspire, empower and enable,” the pair tell us in a blog post.

But here’s the issue, as I laid out in THR. The device is not what will draw us to or keep us from AI apps. What’s more, a device seems to run counter to the very purpose of OpenAI’s mission. Per the story:

“The evidence that it’s the app not the machine is that past attempts at AI-specific devices, from the R1 Rabbit to the Humane AI Pin, have thus far flopped or gotten really bad reviews. But I think even more problematic here is that Altman is making a philosophical pivot undigestible even by his own rhetoric. AI is different than previous technological revolutions, Altman has said (correctly), because it doesn’t simply change what we can do but what and how we think (or, more precisely, don’t need to think).

“The personal-computer brought digital technology to everyday people and the Internet connected us to communities and information we otherwise wouldn’t have access to. But if AI delivers on its promise — and it remains a big if — it will make an even more fundamental change than that, introducing a whole new intelligence to live aside us humans; it’s far more akin to an alien landing on this planet than a product launch or even scientific breakthrough….Something so pervasively existential doesn’t rise or fall based on how cool your device is, and spending $6.5 billion to ensure that it comes in great packaging only makes us wonder if you lack the goods for that pervasive existentialism.”

So get ready for a big push for a device (or wearable) that we can port around with us so an AI Agent can guide us through life. Will we need it? Will we even want it? The answer to both remains unclear. Thanks to Ive-Altman, we will certainly have it. If nothing else it will provide a good distraction while we’re out looking for a job.

3. ALRIGHT, HERE’S THAT FICTIONAL DIVERSION WE PROMISED.

Gabirol

Inbal felt like visiting the file-reloader today. Though, if you wanted to be truthful, it was less a feeling than an imperative. And she couldn’t even say why – she simply woke up with the directive in her head. Like how you feel the urge to buy a pair of sneakers even when the thought of running repels you; you just know life would be paler without them. When you have so strong an impulse you need to act on it.

Anyway, she went to Solomon, who ran the nearby file-reloading machine, and asked if the machine was working today. “Yes,” he said. “So who will it be?”

“First, how do you know I want to bring anyone back?

“Even if I did,” she added, “aren’t you supposed to warn me about the dangers?”

“Even if I warned you, would you listen?” he asked.

Legion in Heaven, he had a point. Solomon knew he couldn’t really stop anyone — when you felt absence so acutely reason had nothing to say — so why even try? Love was potent like that, even when it was a love for someone who didn’t exist.

“Is it worth the pain of fresh grief just to experience this person again for a few minutes?” Solomon asked her. “Knowledge of the risks is much more effective than a warning,” he added, explaining his process.

“Everybody doesn’t experience grief all over again,” she countered.

“Some don’t, true. Could you see yourself being one of those people?”

“I think so,” she said.

“Each must make the decision for themselves,” Solomon said gnomically, and went to retrieve the files Inbal had written on her admission sheet.

Now that they’d gotten that out of the way, Inbal could concentrate on why she came. Creating — re-creating — the person she really wanted to see. Extremely needed to see.

“For argument’s sake, let’s say I wasn’t sure I could be one of those people,” Inbal said, circling back as Solomon warmed up the whole-brain emulator machine. “I still want them in my life now—to share my week, my problems, my life. Camaraderie brings consolation,” she added, reasonably.

“Tell me, is it consoling when you know they’re not actually listening? It just feels like they’re listening. Only a trick, made possible by a few projectors, some diligent file-keeping and one extremely powerful processor,” he said. “Nothing more.”

“Ugh, you don’t have to keep reminding me,” Inbal said.

“No matter,” Solomon answered, “here you go.” Turning a few dials, he made sure the machine was up and running and left the room.

Inbal gazed at the form as it took shape. Looking and seeming so much like her, even though every rational cell in her body knew it wasn’t.

“What have you been up to, my sweet girl?” the figure said as it filled itself in. “Everything in your life – your marriage, your children, your work – how is it?”

Rocking back and forth involuntarily, Inbal sought to compose herself. Echoes of her mother were somehow stronger than the real thing; how was that even possible?

“Utterly great. Perfectly fine. Ontologically wondrous. Never better.”

“Inbal, the more sarcastic you are the more I know things are not fine,” her file-mother said, firm but sympathetic. “Tell me what’s wrong.”

“Liam is staying ‘late at work’ a lot. I don’t know what to think but I think I just don’t want to think it. Kids, well, kids are great, but why it is always great in the abstract?

“Even work, my saving grace, is tiring, with all the politics, the bootlicking.

“Utilizing every trick in the book,” Inbal said as she took stock of it all, “I still feel like I can only carry half the load. Somehow everyone else carries the whole load. I carry half.

“Not even that sometimes,” she added, erupting into tears.

“God, what am I doing,” she said, wiping her face as the figure in front of her remained silent, “I see you for the first time in I don’t know how many years and I just start going on about my problems?”

“Tell me Inbal, my sweet girl, do you ever think of not being with him?” her file-mother finally said. “Effortless, that’s how I would describe my marriage to your father each of those 16 years, as though one of us could say something and the other could just say ‘ditto,’” using a popular family word, “like we not only saw the world the same way but could shorthand our agreement.

“Can’t say everyone’s is like that, though,” her file-mother continued. “Hoo boy, certainly not,” she said, getting a faraway look in her eye. “Not when you look at so many of our friends.”

“Or Aunt Harriet,” Inbal said.

Laughter burst from her file-mother’s face. Overwhelming laughter, the kind Inbal recalled from childhood. Gosh, it was hard to remember this wasn’t her. You sit at the re-loader and, well, it’s true what they say — you get taken right back to when everything was still OK. Those childhood years, so many childhood years, and yet not nearly enough. Oh, to be back there right now. Right at this moment.

Even though, Inbal realized, in a way she was back there — did an intellect or soul need tangible substance to have form; what was an algorithm but a mathematical distillation of the truth; what did it matter how someone came to say what they said if you loved the words they were using?

“So what else can you tell your mother— you know, to bring her joy, unbelievable joy?

“Unbelievable joy! Rudimentary happiness, maybe.”

“Ripples of brightness? Explosions of bliss?”

“Could you the set bar just a little lower?”

“Touches of mirth?”

“This has been so good,” Inbal said, smiling through her tear-streaked face.

“Here, you want to know how to find your purpose, to return from this sadness, to access the light— the source of life, really?” her file-mother said, segueing to the philosophical, like Inbal remembered from childhood. “Easy – you just strive to be true and good; that will give you centeredness, the purity to return from this dark place.

“Don’t ever forget you are who you are Inbal,” her file-mother said. “Even when the world is doing its best to make you feel like you’re not who you are.”

“And most important — you don’t forget that I love you,” Inbal whispered.

“Ditto,” her file-mother replied, before dissipating.

“Bye Solomon,” Inbal barely managed as she sprinted past him and onto the street. Under her sunglasses she could feel tears welling up again. The man was right. She felt a loss so sharp it was as if it had just happened. Her mother, taken from her all over again. Only now she had all the awareness of what happened since. Underwater for so long. Love hard, and vulnerability too. Death victimizing her twice, as it did many who lost a parent young.

What an incredible feeling to talk to her again though. Ecstasy, even just for a few minutes.

(Footnote: An acrostic was a device used by Medieval Hebrew writers to tag a poem or otherwise comment metatextually on the work in question)

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. This year started on kind of a good note. But it’s been fairly rough since. This week? It ain’t good.

SOME JOBS ARE SAFER THAN OTHERS BUT MOST OF US WHO WORK WITH A LAPTOP ARE SCREWED. AI displacement theory. -4.5

AI, NOW IN GADGET CASING: -2.0

IT’S POSSIBLE HOLOGRAMS WILL EASE OUR GRIEF, THEN MAKE IT WORSE: -0.5