Mind and Iron: Superintelligence? Sam Altman says it's coming very soon (😬)

Kamala on Crypto. And Mark Zuckerberg wants to give us the AR glasses our peak-distraction age deserves

Hi and welcome back to another spicy edition of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and chief mixologist of this sober-cocktail joint.

Every week we bring you the best of science, tech and progress — and assess whether it really is that last thing. Welcome/welcome back!

Quick housekeep that we'll be gone next week, back at you the week following. But we’ll make up for it with some doozies this issue.

Sam Altman and Mark Zuckerberg, the two people who are not only the faces of but also the engines behind the machine-thinking, digital-tech-everywhere world we're hurtling toward (or that’s hurtling asteroid-like toward us), each had major pronouncements this week. In the latter case, actually accompanied by a product! Sort of. We give you what you need to know and offer some food for thought.

And speaking of powerful people making pronouncements, Kamala Harris makes a tech pledge, and it’s kinda troubling. Call us the day after summer camp, because we got the full unpack.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

“We don’t think people should have to make the choice between a world of information at your fingertips and being present in the physical world around you.”

— Mark Zuckerberg, announcing Meta’s new AR glasses Orion (or just giving the lodestar for our new digital-ubiquity world)

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Sam Altman says the day of superheroic machines is soon; Kamala Harris says she is here for crypto; Mark Zuckerberg says the glasses that glue the smartphone to our retina are coming

1. PREDICTIONS ABOUT WHEN COMPUTERS MIGHT REACH THE MILESTONE OF “SUPTERINTELLIGENCE” HAVE ABOUNDED FOR YEARS.

This is the idea, popularized by Nick Bostrom in his book of the same name exactly a decade ago, that machines will not just achieve the ability to reason like a human but grasp concepts so esoteric humans can’t even understand their genius. Pretty soon the machine starts multiplying itself like Scarlett Johansson at the end of "Her." "An intellect that is much smarter than the best human brains in practically every field, including scientific creativity, general wisdom and social skills," Bostrom wrote way back in the 90’s and many times since.

The idea relates to, but stands apart from, artificial general intelligence (AGI). While sometimes used interchangeably these days, AGI connotes a computer that can reason like a human, while superintelligence outpaces what most humans and even humanity itself has historically been capable of achieving. It's the difference between when a computer can surpass Stephen Hawking (superintelligence) or barely get to the level of some Substack schmo named Steve (artificial general intelligence).

OpenAI chief Sam Altman this week made his own prediction, in a rare post on his personal blog. We’ll get to that in a second. First, here are some of the forecasts that have been made over the decades:

--In the middle of last century Isaac Asimov suggested, in the collection this newsletter is named for, that the idea of super-intelligent "positronic robots" would be firmly in place sometime by the 1990s.

--The futurist Ray Kurzweil has long held that after achieving AGI by 2029, machines will hit some form of superintelligence — he calls it becoming “profoundly superhuman” — over the next number of years, eventually allowing (incentivizing? forcing?) humans to merge with said intelligence by 2045. So, 2045.

--Bostrom himself said, writing in said 1990's (without the help of positronic robots), that superintelligence would be reached by 2033. Bostrom in his book a decade ago gave a longer window that stretched into the back half of the century.

--In a survey of more than 350 AI experts, a majority said it would happen between 2040 and 2050.

--In perhaps the most brazen prediction, the fanciful futurist and robotics creator Ben Goertzel says we can have "a radically superhuman AGI" that "can do engineering and science at a human or superhuman level" by the end of the decade (though he breaks the futurist's first credo, which is never make any predictions on a time horizon where they'll still remember what you said).

I tell you all this not to defrock Altman. I tell you all this to note he's in very good company. That company just happens to be on shaky ground.

So here's what Altman wrote:

“It is possible that we will have superintelligence in a few thousand days; it may take longer, but I’m confident we’ll get there.” And what will this mean, according to him? “I believe the future is going to be so bright that no one can do it justice by trying to write about it now; a defining characteristic of the Intelligence Age will be massive prosperity.”

He adds, “Although it will happen incrementally, astounding triumphs — fixing the climate, establishing a space colony, and the discovery of all of physics — will eventually become commonplace.”

So let’s take the calendar prediction first. Tomorrow-is-always-a-day-away syndrome permeates all of these projections, and Altman’s is no different. In fact in a single sentence he encapsulates the two-footing that the worst of these prophesies fall into — grabbing you with their imminence while protecting them with their qualifiers. A few thousand days would be no sooner than 2032 and no later than 2035 (!)] But then, he also said it “may take longer.”

But the biggest issue is not the timeframe when it can be achieved — it’s what happens if it is.

Many of the above voices actually have a nuanced take on whether superintelligence will be good or bad for humanity. Bostrom is pretty keen to emphasize the risks; Kurzweil is much sunnier. Asimov is especially balanced in suggesting how it could really go in either direction depending on how we marshal it.

For Altman, however, this superintelligence is pointed in one direction: up. The number of positive consequences just keeps growing, according to him. And he dismisses out of hand the prospect that a machine that can completely outpace any human thought might pose some dangers for, you know, the humans. (Do superior intelligences always treat lower intelligences with the latter’s best interests at heart? The history of our planet would like a word.)

Yet Altman writes, “It will not be an entirely positive story, but the upside is so tremendous that we owe it to ourselves, and the future, to figure out how to navigate the risks in front of us.”

Chalking it up to “deep learning” — a kind of squishily used term that suggests machines extracting meaning from layers of data to simulate the human brain — he said mankind would reach new heights. “Deep learning works, and we will solve the remaining problems,” he says.

Altman, of course, is not an unbiased witness. He has at least three agendas in advancing this superintelligence-now case. First, it accords with the general market mission of OpenAI and investor Microsoft, which, if it’s going to be pushing hard into AI, needs to justify to the money-shellers why it’s doing so.

Second, it accords with the particular mission of Altman, who in contrast to Musk and many of the board members he deposed, wants a full-speed ahead approach to AI, also known as accelerationism.

And finally, it helps spur the investment in and production of chips (which OpenAI needs) while also lowering the possibility of regulation. Regulation that, not insignificantly, Altman is now facing with an AI liability bill currently on Gavin Newsom’s desk that we’ll dive into in a later issue.

Altman gives away the game a bit when he writes, “If we want to put AI into the hands of as many people as possible, we need to drive down the cost of compute and make it abundant (which requires lots of energy and chips). If we don’t build enough infrastructure, AI will be a very limited resource that wars get fought over and that becomes mostly a tool for rich people.”

Which you hardly need an AI to translate as “Let me do my thing, government people.”

For a rather different view of superintelligence and where it could lead us, listen to the words of the University of Louisville scientist and AI safety pioneer Roman Yampolskiy. He slyly undermines a lot of Altman's assumptions. To drive toward superintelligence, he says, is to deliberately remove people from a human equation. Essentially, he argues that the risks outweigh the rewards — by a wide margin.

Now, I’m not sure where I stand on Yampolskiy. As many of you longtime M&I-ers know, I'm much more worried about immediate and tangible dangers to swapping in computers where minds once stood — hidden bias, brain atrophy and the replacement of genuine human connection with the machine kind, for instance. Focusing on computer takeovers in some far-off age of superintelligence obscures some more pressing dangers.

But that doesn't mean computer takeovers are entirely out of the question either. If the Altmans of the world have shifted the language from ‘AI can be a welcomedly helpful tool’ to ‘AI can be a utopia-creating force that solves climate and builds space colonies,’ then it seems only logical to consider the opposite, dystopic view too.

At least, Yampolskiy makes a strong case. I'll leave you with these provocative ideas he recently shared with the UofL News about the risks of superintelligence.

"I don’t think it’s possible to indefinitely control superintelligence. By definition, it’s smarter than you. It learns faster, it acts faster, it will change faster. You will have malevolent actors modifying it. We have no precedent of lower capability agents indefinitely staying in charge of more capable agents.”

"Until some company or scientist says ‘Here’s the proof! We can definitely have a safety mechanism that can scale to any level of intelligence,’ I don’t think we should be developing those general superintelligences.

"We can get most of the benefits we want from narrow AI, systems designed for specific tasks: develop a drug, drive a car. They don’t have to be smarter than the smartest of us combined."

2. POLITICS-SMART, POLICY-CLUELESS.

A politically savvy type I know once used that phrase, and I've found myself flashing back to it from time to time. It means, more or less, undertaking an action that might get you some support in the short term but is bad practice if you actually have to go through with it.

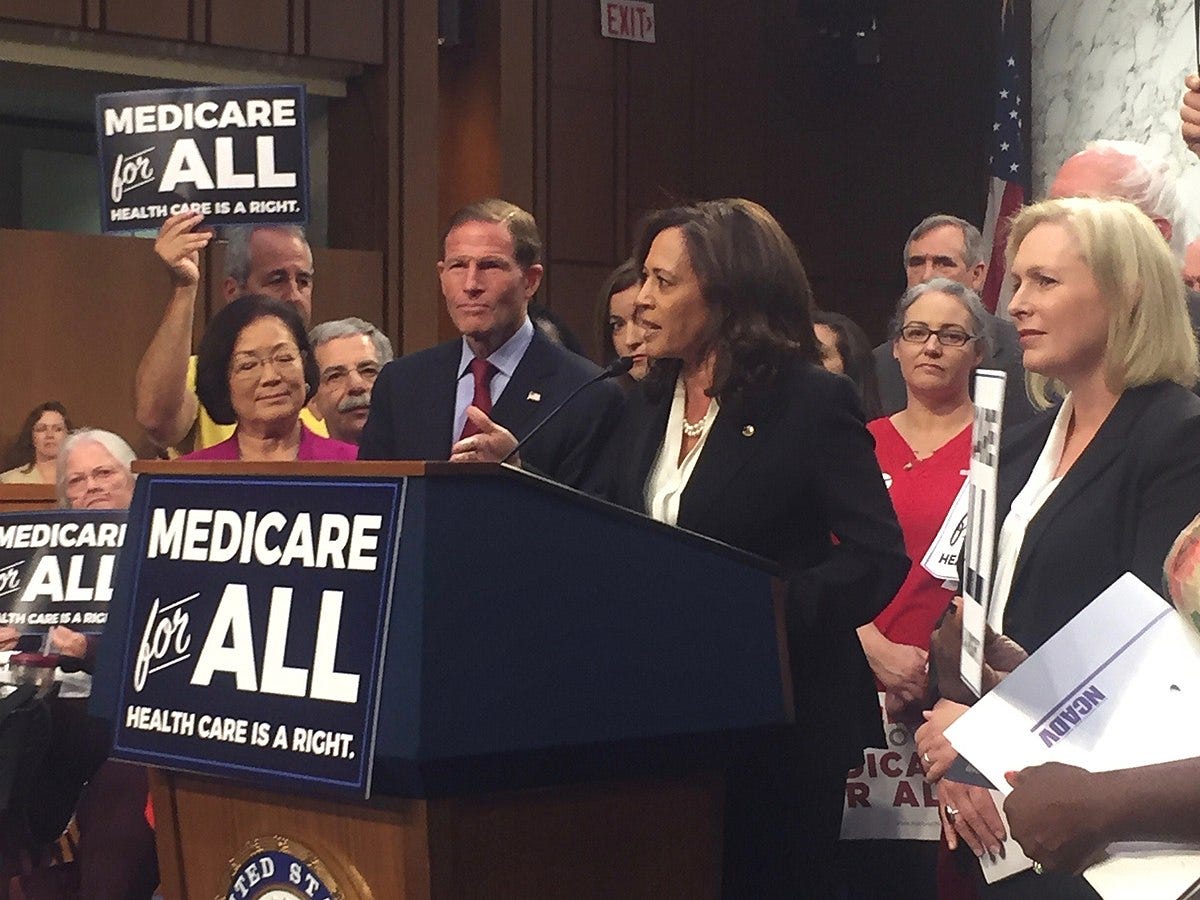

I thought of that this week when Kamala Harris, campaigning in downtown Manhattan, made the following comments.

“We will encourage innovative technologies like AI and digital assets while protecting our consumers and investors,” she said at the event, in which she raised 27 million (presumably real) dollars.

So the part, about AI is more of a snooze. She's definitely said more critical things before (and was part of a a spring 2023 meeting with Big Tech executives at the White House to talk safety). But what does it mean to "encourage" AI? Who? With what?

Yet the comments that came second — the crypto ones — are worth noting. First, as a candidate Harris has never said anything about crypto. Second (and related to the first), crypto has become a big hobbyhorse for Donald Trump lately, as he announces vague crypto projects.

He and his two oldest sons (have there even been more apt poster-children for vague crypto projects?) have been talking up the idea lot. "Crypto is one of those things we have to do," Trump said last week, announcing a vague crypto project. "Whether we like it or not, I have to do it.” That sounds enthusiastic.

Anyway, what such mushiness means in the real world is unclear — he has no launch date and the people running it have almost no executive experience, and also we don't know what "it" is — but the point is some of the people he really needs to vote for him reside in big crypto-investment states (Nevada, for instance, has the fifth-highest rate of crypto adoption.) Not to mention the people he really needs to contribute money to his campaign, part of the whole shift to Trump among some SV titans.

Just as we were putting the issue to bed, an investment advisor who once counseled the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation named Alexander Blume suggested this possibility even more strongly to Quartz. “With over 50 million US crypto owners, many of them passionate, single-issue voters, there is a chance their vote could be decisive in swing states like Michigan, Wisconsin, and North Carolina,” he told the outlet.

Of course Harris knows this, and that's why she's sounding her own pro-crypto note. (On Wednesday she echoed the comments at a campaign event in Pittsburgh.)

There's no earthly policy reason to talk about crypto now — it's not anywhere near the list of most important concerns facing this country. And it's not on anyone's policy agenda. Regulation is hardly strong and it's not like there's some concerted federal push to make it stronger, even post-Sam Bankman-Fried. In fact this week one of the few people actually trying to do something about all the shadiness, SEC chair Gary Gensler, was on the Hill getting grilled by Congress that he was doing too much.

If Harris should be saying anything about crypto, it's to question it. I covered crypto at the Post, and the amount of scams are unceasing and tragic. So is the environmental toll. And the use cases, well, outside of some transferring money to the developing world, they ain't exactly jumping from the gallery.

Oh yeah, and there are all the high-flying crypto executives who have been sent to jail. If Harris wants to live up to her prosecutorial pitch to go after bad actors on behalf of the people, she should be talking more like Gensler, not Trump.

Ah, but there is one interest being furthered here — that of the crypto industry, which has spent $119 million on crypto-friendly candidates so far this election cycle. (Much of it is via a Super PAC called Fairshake.) Ripple, one of the crypto companies Gensler is pursuing in a lawsuit, actually bragged about the potential for political influence back in June.

You could practically hear the torment in the voice of California Democratic Congressman Brad Sherman, who is a major crypto-regulation voice but supports Harris. “The crypto people are flashing huge amounts of money,” he said in a Politico story Thursday. “But ultimately I think that Harris will stand firm.”

Talking about crypto on the campaign trail may be seen as harmless, a way to gather a few easy votes. Promise now; deal with the effects — of regulating horribly pollutant crypto-mines, of fighting the wildfires of money-laundering that crypto encourages -- in office down the road.

But it's setting a bad tone, making it seem like an issue of bipartisan good for the American people when it isn't. Also, can you really walk back the pro-special interest comments after you spent time making them? Isn't that not how Big Money in politics works? Even Big Bitcoin Money? More likely the policies then get adopted, in this case allowing the bitcoin bubble to keep being inflated for no earthly social purpose.

Crypto has yet to prove itself as the future of anything. Pandering, though, is timeless.

3. FINALLY THIS WEEK — THE IDEA THAT WE’LL ALL SOON BE WALKING AROUND WITH OUR EYES STARING AT A SCREEN WE WEAR ON OUR HEADS INSTEAD OF CARRY IN OUR HANDS.

Such notions have been around since the failed 2010’s-era days of Google Glass and Apple’s bid in 2024 to make the case for the Vision Pro (the beginning of the journey for the company, I suspect).

But Mark Zuckerberg entered the chat this week — or, we should say, re-entered the chat since the company has had those Ray-Ban glasses for a while.

Zuckerberg unveiled something called Orion, a pair of Augmented Reality glasses that look almost respectable, in that let-me-don-my-Buddy-Holly-frames-this-Pavement-show-is-going-to-rock late-90’s way.

Unlike the Ray-Bans, which mainly are a speaker-and-camera deal, these things are much smarter glasses. They’re meant to let us message, watch videos, play games and, with the help of AI, churn out data about the world around us (the style of a building, the ingredients in a dish). Basically they let you do what a really good AI-enabled phone will soon let you do. But as something worn and integrated into us.

(You do need a wristband and a whole large rectangular receive-type thing that, oh yes, you also need to carry around with you; hands are not obsolete yet)

Also unlike the Ray-Bans, you can’t buy them. They’re cost like $10,000 just to produce. This is a proof of concept, for journalists, investors, dreamers but not really anyone who might use them.

Part of why they glasses are so expensive is because they use silicon carbide for the lenses instead of plastic or glass. This makes the resolution much better. But again, also mythical.

I haven’t tried them. But the reviews are seem reasonably positive. As Alex Heath wrote in The Verge, “The quality of Orion’s display is surprisingly good given the form factor. Video calls look crisp enough to feel engaging, and I had no problem reading text on a webpage that was several feet away.” (That Slate writer above felt differently, fashionwise.)

You could almost — if you squint — start to see a vision of the future here, in which instead of looking down anytime we want to learn or communicate or watch we keep looking ahead, with AI supplying us with info and companionship we normally have to manually, as it were, seek out in the phone age.

Zuckerberg bet big on the purchase of Oculus for $2 billion a decade ago, and has been pushing the Meta Quest headsets with mixed results in recent years along with those Ray-Ban glasses.

Now he thinks this new breed of AR glasses can be our future. “A lot of people have said this is the craziest technology they’ve ever seen,” Zuckerberg said while announcing them at Meta’s annual Connect developer conference this week.

Of course even if it is that crazy, and even if the form factor is that smooth, you wonder what it will all lead to. I’m not so naive as to think we won’t want more connectivity; the last three decades has been an object lesson in the opposite of that.

If a device like smart-glasses lets us interact with the world more easily, you can bet sooner or later we’ll embrace them. Will this be to the good? That’s another matter. For all the ways people looking down at their phones can be annoying, it requires a conscious decision, something that separates our physical from our digital lives. Looking out through glasses is not. People may not have to make a choice between these worlds, as Zuckerberg said, but they should have the option. Because if people are looking at a screen while they seem to be looking at our eyes, what are they really looking at? And if we’re never really looking at the world without a screen over it, how much are we really seeing?

Perhaps that’s why these glasses haven’t taken off yet — most of us don’t really want this kind of commingling. Still, in all the ballyhoo of announcements like this, it’s worth stopping to ask the right questions. A lot of the discussion about the glasses is how we’ll look in them. Just as important, though, is the vision of human interaction we’ll advance when we put them on.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. Last year ended with a score of -21.5 — gulp. Can 2024 do better? The summer wasn’t great. And neither is this week.

SUPERINTELLIGENCE IS COMING? We should probably be a little more vigilant -2.0

ET TU, VP? Kamala goes krypto. -2.5

META GLASSES COULD CURE OUR PHONE ADDICTION BY PUTTING SCREENS CLOSER: -1.5