Mind and Iron: The AI Pioneer Who Fears He's Dr. Frankenstein

Turing Award drama. Also, do we really want to Google differently?

Hi and welcome back to another saucy episode of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and chief pitmaster of this media vegan BBQ.

Every Thursday we gaze upon technology and the future to determine where it's headed and how we should feel about said direction. Please consider supporting our independent mission.

This week we've got a juicy tale that is a personal drama and also a philosophical drama and also a literary drama but really just gets down to the drama of what we're creating with this whole AI world and what caution should attend it. The story starts with a million-dollar prize and goes from there.

Also, something that speaks directly to the way many of us interact online: Googling. It's been changing for a while. And now the transformation is really on. We'll fill you in, no searching required.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

“Engineering practice has evolved to try to mitigate the negative consequences of technology, and I don’t see that being practiced by the companies that are developing [AI]."

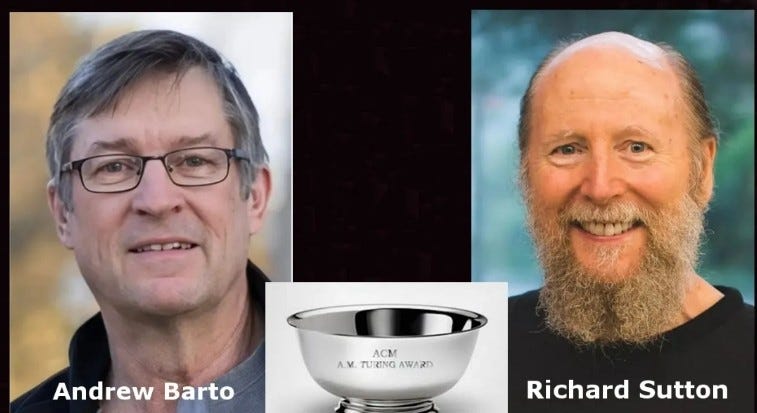

— Turing Award recipient Andrew Barto, adding his weighty voice to the slow-our-roll chorus

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Paging Dr. Frankenstein; Google levels up to AI Mode

1. A FEW MONTHS AGO THE PHYSICS NOBEL PRIZE WENT TO A SCIENTIST WORKING IN AI WHO WAS ENTIRELY UNSURE HIS WORK MERITED SAID PRIZE.

The machine-learning pioneer Geoffrey Hinton accepted the Nobel for his AI research and promptly used it as an opportunity to say we need to...slow down our AI research. "We have no experience of what it’s like to have things smarter than us," he said. "We... have to worry about a number of possible bad consequences."

One more of these is a trend, because this week it happened again — a major honor went to someone whose advancements led to the AI world we have today (and will lead to even more tomorrow) even as the honoree looked at the gold plaque and asked, "eh, we so sure about this?"

The winner in question is Andrew Barto, a UMass-Amherst computer scientist, who, along with the University of Alberta's Richard Sutton, on Wednesday received the Association for Computing Machinery’s prestigious $1 million Turing Award, aka the Nobel of computing. The two had written a book back in 1998 about a new technique in "reinforcement learning" (more on that in a second) and have indeed dedicated their whole lives to the study of how machines can become more intelligent. Upon being told he'd won the honor, Barto promptly offered some skepticism to The Financial Times.

As the paper has it:

“'Releasing software to millions of people without safeguards is not good engineering practice,' said Barto, likening it to building a bridge and testing it by having people use it. 'Engineering practice has evolved to try to mitigate the negative consequences of technology, and I don’t see that being practiced by the companies that are developing [AI],' he added."

This assessment seems a little less sharp than Hinton's, because Hinton is focusing on the possibility that the technology itself gets away from us, while Barto is focusing on the people who could exploit it for bad aims. But a distinction without a difference, really, because the ratio of autonomous-badness to people-exploitation-badness seems in the final analysis to matter a lot less than the fact that there's badness. According to Barto, AI brings simply too much risk to let for-profit companies operate unfettered. (And obviously forget about any current U.S. governmental authorities stepping in to stop them; President Donald Trump has already revoked the Biden administration's humble efforts to do so.)

What you have for both Hinton and Barto are situations that are at best inherently deeply unknown and at worst, once we do know it, very detrimental to this whole here human project. The people who created the very thing we're embracing are telling us they have concerns — even at a moment when they're being celebrated for that creation. It would be like Bob from Accounting standing up at his Employee of the Month lunch and saying the numbers he filed really don’t add up. Only with, you know, slightly bigger stakes.

But let's dive more deeply into why Barto is uncomfortable — into what his research yielded that makes him feel so squirmy.

Of all their contributions, the biggest addition Barto and Sutton made to our AI landscape is a technique called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback, RLHF. These are actually two ideas. The first is Reinforcement Learning, the principle, which you may know, by which a machine intelligence gets better by doing something again and again. Much like a human or other animal learns over time to better walk the maze (figurative or literal) to so they can reach the cheese (figurative or literal), so too machines can get better at doing XX task by trial and error. If every time you talk back your parents they take away your videogame console, you learn not to talk back. Same with computers.

The second part is newer and more surprising — the human feedback. This is the part where the machines get trained by humans. That is, rather than just stuffing a model with data and having it try to execute a task under a programmed mechanism of rewards and punishments, Barto and Sutton found that the system will work a lot better if the humans are there at the start to help it along, telling it manually what is most likely to garner the reward — gently and painstakingly guiding it to the most authentic responses until it figures out how to improve on its own. The maze is still there, but now some helpful guides are standing around to make sure no one bumps into walls.

Or, to put it another way, if a machine is to think on its own, it needs a human to tell it how to do so. (Just at the beginning; once it does the humans are no longer needed.)

I had a friend who was involved in said training. She sat in a room all day and graded a model on whether what it was saying made sense or not. (She was also under some kind of crazy NDA, which doesn’t seem like a red flag at all.)

Anyway, that technique was a major breakthrough. The intercession of the humans allowed the machines to learn much more efficiently. The proof was in the product. In 2022 Meta had actually released an AI that didn't get trained with the human-feedback part. It wasn't very good and was quickly shuttered. Several weeks later OpenAI came out with ChatGPT, which did get the Human Feedback half of the RL equation. And it started a revolution. Everyone began using ChatGPT. It just seemed so authentic, so human-like. That's the human-feedback factor.

Google and OpenAI continued to iterate using this approach, taking the technique and applying it not just to text prediction but to reasoning, with newer models from both companies, like OpenAI's o1, capable of math thanks to RLHF. Eventually, the theory goes, RLHF can get us to AGI — the alphabet soup that in plain English means this technique of humans training an AI can actually yield a machine that thinks as well as a human.

This has an interesting literary implication. It complicates the narrative of an out-of-control intelligence we had nothing to do with. We are, like Dr. Frankenstein, directly enrolled in the project to create something better than ourselves. I don't blame my friend; she was a freelancer who just needed a few bucks. But she and the hundreds of people who sat with her were literally building the creature with their bare hands.

This RLHF world also has some head-spinning philosophical implications. It means that AI is not really as powerful as we think, that it needs a certain kind of humanity to achieve a human-level of autonomous intelligence. Chalk one up to human supremacy. But it ALSO means that once humans do intervene, AI can take it from here — that at some point, after people give it some helpful guidance, AI can run with the learning as well as a human (and, given the far greater speed at which it can calculate, eventually better than a human).

Perhaps it's no surprise, then, that Barto in particular is so concerned. After all, he's seen firsthand what AI can't do, what it needs us to do; he has seen in dramatically vivid and linear fashion that it’s the human input that supercharges AI to the next level. It is from this place that he is asking whether we should proceed full-speed. Our current retelling of Shelley’s story isn't just populated with Dr. Frankenstein as an abstract solitary figure of science. It's populated with many Frankensteinian assistants. The AI needs us — all of us, every person who can get in there and train it — to become what it is.

And in this reboot, Barto/Dr. Frankenstein doesn't like what he's started and goes out and shouts out across the Swiss Alps about what the assistants are up to.

The problem is in this version he's already sold the lab to someone who doesn't care. And so what can Dr. Frankenstein really do to stop it? At some point, all the prizes in the world don't get you a key back into the building.

2. IF YOU’RE A SEMI-REGULAR READER OF THIS SPACE YOU’RE FAMILIAR WITH THE CHANGES GOOGLE has been implementing in their searches and how we feel about them. Last year brought us “AI Overview,” which as you’ve no doubt encountered is a synthesis, now with some afterthought-y links, of answers that were perfectly findable with traditional search methods.

This week the company began testing a new souped-up version of that system called “AI Mode.” Built on its Gemini 2.0 model, AI Mode is supposedly bigger, better and more accurate than AI Overview, which is a little like saying a nine-year-old Little League pitcher is more accurate than a racoon; the bar just isn’t that high.

In announcing the launch, Robby Stein, Google’s VP of Product-Google Search, promised a beautiful seamless experience that will instantly make our digital lives easier, cheerfully writing “You can ask anything on your mind and get a helpful AI-powered response with the ability to go further with follow-up questions and helpful web links.” Well there you go! Internet detritus problem solved.

(Stein also said that “we’ve heard from power users that they want AI responses for even more of their searches.” Which seems hard to believe, as no human I know has actually said this.)

Douglas Adams once said that “We are stuck with technology when what we really want is just stuff that works,” and I can’t help feeling a version of that here, the introduction of a solution to a situation that isn’t really a problem.

Btw, when I put that quote into Google, AI Overview told me that it “highlights the frustration of dealing with complex, often unreliable technology when simple functionality is desired,” a searing level of insight that definitely could not have been achieved by a common house parrot.

If you squint hard here you can find a use for AI Mode that synthesizes a bunch of Web sites in a way that might have been tricky to track down on their own. In his post Stein promised that AI Mode will allow you to “ask nuanced questions that might have previously taken multiple searches — like exploring a new concept or comparing detailed options — and get a helpful AI-powered response.”

The problem, of course, is that these AI systems are built on top of the existing Web. And the existing Web, as we know, is full of garbage. It takes a discerning human mind to separate the hogwash from the genuinely true and useful, and the idea that any current machine model can do that faster or better than most of us is pretty close to laughable.

The value proposition here is some kind of “2001”/“Star Trek”/“Quantum Leap” trusty info-bot that is always helpfully there for us with a clean informational answer — a concept that seems nice until you realize all of those entertainments neglected to account for the fact that in a media-overload society information is rarely clean and, in any event, depending on who or where we are we may be seeking more than one answer.

(AI Mode is clearly being built as a competitive response to Perplexity and ChatGPT’s Search Option, which offer their own issues. AI Mode will also involve advertising. What this all does to the companies that rely on Google Search for traffic and how it further allows a Big Tech company to profit off work that it didn’t create is another matter, on which you can read more here.)

Google search is a victim of its own success. The current algorithm is solid enough that when seeking out information we usually find what we’re looking for pretty quickly. And if we need something more complex, I’m not sure I trust a machine, which can have a hard enough time with a simple query, to know or find it better than we can ourselves.

Google is also a victim of being limited to what’s already out there. The real problem with the Internet and its morass of inaccuracies and nonsense and disinformation is that it’s a morass of inaccuracies and nonsense and disinformation. As Google is not repopulating the Internet, it can’t do anything about that. It can just try to find tools that can cut through that, and then tout some Great New Internet that’s really the same old Internet with different window panes. It would be like me telling you your fridge is filled with rotten leftovers, but instead of leaving you, who at least instinctively understands its contents, to go through the shelves I say that you can just turn out the light and I’ll pull out some stuff for you. Chances are, the food is still spoiled.

But AI Mode is coming. And because Google is pushing it — and because life is harried enough — these mono-answers will likely soon start dominating over traditional democratic Web searches. Get ready to have a machine even more assertively tell you what the answer is and even more definitively push original Web sources to the side — making the right answer just a little bit harder to find, daily life just a little more inconvenient and the truth just a little further out of reach. Other than that, it’s a great system.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. This year started on kind of a good note. But it’s been a little rough since. This week? Nothing great.

AN IMPORTANT NEW VOICE QUESTIONS THE SPEED OF AI RESEARCH: Will we listen? +1.5

WEB SEARCHING IS ABOUT TO GET A LOT LESS EFFICIENT UNDER THE GUISE OF EFFICIENCY: -2.5