Mind and Iron The Future of Reading (Yes, Reading)

What happens when AI is scanning text for us. Also, what's really behind those Waymo torchings?

Hi and welcome back to another salty episode of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, senior editor of tech and politics at The Hollywood Reporter and lead pinwheel-vendor at this journalistic street fair.

Every week we bring you all the essentials on our quickly changing future. Please consider supporting our mission.

As we write this war appears to be brewing in the Middle East. Which makes tech news, critical as it is, pale in comparison. Who would have thought that Alex Padilla getting dragged from Kristi Noem's press conference would be the second-craziest thing to happen today?

Of course, global news can also be tech news. That's true with our post from the fall about Israel's attack on Hezbollah pagers — you can read that here. And it's true at home with anti-ICE protests taking on a potentially techlash-y dimension. We wrote about the topic this week for The Hollywood Reporter, and will give you some of the breakdown below. (Also, if you want to read our special issue from last May about the future of political violence, click over this way.)

And our main event: the future of reading. What is that future, in an age when an AI can increasingly read — or at the very least summarize — for us? A new set of glasses from Meta poses the question more urgently than ever. We'll tell you what you need to know.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

“If you see the anti-ICE protests as defending the idea of being human and caring about human values, then destroying the property of a trillion-dollar corporation whose goal is to make human labor obsolete makes perfect sense.”

—Wendy Liu, author of the 2020 manifesto “Abolish Silicon Valley,” on the unlikely tech connection to the immigration protests.

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

When reading is for suckers; Burning self-driving cars

1. WHAT IS THE FUTURE OF READING? I don't mean that in a schoolmarmish scolding way, like kids today don't read enough and what is the future of literature if Jane Eyre isn't embraced like it was when I was your age?

I mean that in a very basic, bar-is-so-low-even-the-12th-man-on-the-Washington-Wizards-can-clear-it kind of way. As in the, the very act of reading: will it still exist when our grandkids are our age? Or, in, like, five years?

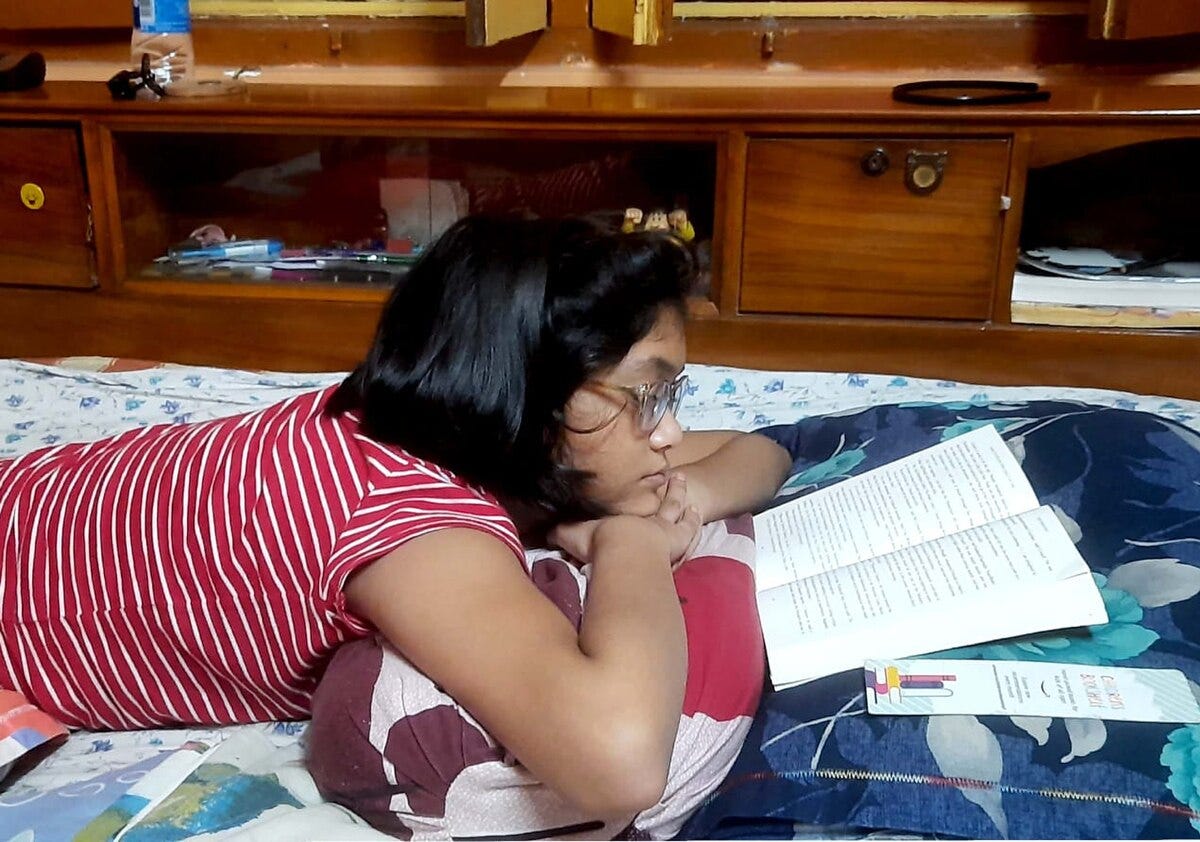

Last week I visited the Meta offices to get a glimpse at what its new Ray-Ban AI glasses could do. A lot, as it turns out. One of those things is read for us. You put on a pair of glasses, look at a block of text, and then hear an auto-generated voice in your ear telling you, in much more concise form, what's on the page in front of you.

What the program is actually doing is combining several functions — capturing all the text with a camera, putting it through an image-to-word translator, using an LLM to synopsize those words, then using a multimodal program to read you that synopsis. But basically, it's reading for us.

I should caution the tech is not quite there yet; the glasses only get a page’s most basic rudiments. But sitting through the demo I didn't have to engage my imagination too hard to see a much different world than our own — one in which "reading" is little more than a quick stare at a page followed by a sweet summary in our ear.

For now, Meta is keeping the focus on something you either don't want to read or don't have time to read, like that museum blurb you just photographed you'll absolutely return to once you’re home and off your feet. More critical applications also beckon — like medical information in a foreign language. If you're in a hospital in Fes with suspected food poisoning, you don’t want a crash course in Darija. You just want to know how not to die. Meta Ray-Bans are here to help.

But these very specific inarguable use cases often bleed into more general-interest ones when the market and money arrive. I mean, the Internet was developed for the military. Reading summaries could easily go from hospital warnings to news sites, then to homework, to work email, to church bulletins and on. Pretty soon you're putting on these glasses anytime you've got a book-club deadline. Colson Whitehead is great, but who has the time? Reading will be for the retired and the gullible. Why churn butter when a tub of Land o' Lakes stares back at you from the supermarket aisle?

And we’ll absolutely see this in professional contexts, the AI reading where the person (employee) once did — the paralegal that once combed through case law, the Hollywood assistant slogging through spec scripts. It's funny: we've focused so much on how ChatGPT and other programs can write for us, we’ve not much stopped to think whether it could read for us too. (Technically it’s actually a little harder, since the predictiveness element doesn’t apply. Still.)

"Your grandchildren will be the last generation to read and write. I think we're at the dawn of a new era of AI-enabled communication," said a tech executive named Victor Riparbelli in a recent Ted Talk, and while as the head of a video-based platform called Synthesia he's hardly the most impartial person to make the case, he does offer a plausible argument for the ease of video and audio communication that, when combined with AI reading and writing, does inch us closer to that vestigial reality.

Now all this sounds suitably dystopian, and it is. We can deal with our brains forgetting how to puzzle out maps in the age of Waze. We can even deal with an AI scheduling our meetings or running our online errands, as it likely will soon do. But reading? Do we really want a machine doing that for us?

So allow me to go a little Yuval Harari on you for a second. I'm not sure this is reassuring. But it is...contextual.

For many centuries of course man didn't read, first because writing wasn't invented and then because publishing wasn't invented. Movable type didn't come around until the 15th century, and even in more educated societies about half of all people still didn't know how to read at the start of the 19th century. That all changed over those 100 years, of course, and by the start of the 20th century most people in the developed world knew how to read.

Still, that means reading is hardly an innate human activity, historically or evolutionarily. The first man walked this earth around 2.8 million years ago, and for about 2.78 million of them most people didn't scan their eyes across a bunch of characters to understand a set of meanings. Socrates actually didn't think reading was that useful — in fact he thought it would make people lazy and erode memory; how hard did your brain have to work if you could put everything down for posterity?

That's of course comical given what we now know about the importance of reading for memory and the human brain (and reminds how technology eventually proved beneficial is often initially feared). Yet recalling such Socratism it's possible to see a future of human reading not as an inevitability but an uncertainty, insane as that sounds (and insane as it is to write knowing how you'll consume this message). I mean, there are a lot of things we didn't do for a long time, and it doesn't mean we should go back to not doing them. But civilization was able to thrive and people could lead happy lives, so to assume that this is a skill that must be taught, practiced and cherished is to forget that history.

Now that we know, do we want to go backwards? Well, no. But humans militate toward the convenient, and if we can seemingly achieve the same effect while putting in a lot less labor we usually do it. Which makes me think the Meta glasses and their ilk will dramatically change our reading habits and abilities in the nearish future.

So where will that leave us? Evolutionary scientists simply have no recent fact pattern for the conscious abandonment of a skill like this. Reading has an incredibly beneficial effect on our brains and even our longevity, and what would it mean to let the muscle go flaccid?

Nor do social scientists know. It’s simply hard to decode a world so scrambled. Will reading in this AI-assisted age become a privilege only for the elite? Or could it be, head-spinningly, the opposite — only the POOR will be able to read because they can't afford an AI to do it for them? This status stuff has a weird way of reversing. Corpulence used to be a sign of wealth. In the Ozempic age it's the opposite.

There is one silver lining to an AI reading-program. Too much of our reading now, most of us feel in our souls, is done to no particular end. The average office worker receives 120 emails per day, and ten of them have the information we need. This didn’t have to be an email.

If some of our hours scanning text could be skipped thanks to an AI doing the grasping for us, does it free up our reading time for something more valuable, more pleasurable? That is, would we still spend the same amount of time in the day reading, just on the stuff we wanted to? Most of us can't imagine ever giving up the joy of a "Harry Potter" or Stephen King or other literary property that lodges in our heart, and maybe now without all those emails to run our eyes over we'll have more time for it.

That's the optimistic view, anyway. And if there's one thing reading all those self-help books have taught us, it's to hold on to optimism.

2. YOU PROBABLY HEARD ABOUT THE WAYMOS THAT GOT TORCHED at the anti-ICE protests in Los Angeles this week.

These are the Google-owned self-driving Jaguars that cruise around many West Coast cities, paying a lot more attention to safety than a lot of human drivers on the roads, as they drop off and pick up passengers. And a bunch of them were burned pretty lustily on the streets of downtown.

You may have wondered upon hearing this news if it was a conscious political act — part of a “techlash,” as The Economist-coined phrase describing acts of violence against Big Tech’s incursion into our lives has it. Or were Waymos just an easy vandalism target?

I spent a solid day reporting on the matter for THR and still don’t know. Did the people who burned the cars want to strike a blow for humanity they felt was lost both in the immigrant raids and automated taxis? Or did they just need to set something on fire?

I talked to an anti-Silicon Valley activist, Wendy Liu, and she had a interesting quote. “If you see the anti-ICE protests as defending the idea of being human and caring about human values, then destroying the property of a trillion-dollar corporation whose goal is to make human labor obsolete makes perfect sense,” she said.

And I talked to a former FCC chairman, Tom Wheeler, who’s the author of the book “Techlash,” and he said he didn’t think it was that at all.

But in a way, it doesn’t really matter. Because the coming months and years I think will be filled with such gestures. Their motives may be ambiguous and their actors even murkier. Who did it and why might be, with rare exception, something we never fully find out. What does matter is how these gestures will play. Because these acts of techlash are kind of a Rorschach test — we see in them our own frustrations and misgivings.

Tech will make our lives easier in a lot of ways, no doubt. We just don’t tend to have political acts expressing that (we just open our wallets). But we do have 100 different words for our we feel a big corporation might be throttling us. How we commit small gestures, or even how we read dramatic violent gestures that many of us would never undertake, will I think be a way of uttering that speech. And, possibly, even the beginning of taking (healthier) action to effect some change.

As I wrote in the piece, “The many perils of the computer-model takeover — whether it’s displacement, disinformation, bias, an outsourcing of human thought or a reduction in human contact — are not easy to see; unlike looms or railroads, a program that thinks hardly asserts itself physically. In such a world, a self-driving taxi, while an imperfect symbol, may be the best we have.”

A few destroyed auto-taxis on a protest street seem far away from our daily existence. But they tell us an encyclopedia about how our landscape, literal and emotional, might look when it’s filled with the trappings of an automated future.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. This year started on kind of a good note. But it’s been fairly rough since. This week? Only slightly better.

READING, WHO NEEDS IT? -4.0

THE TECHLASH IS BEGINNING. Ok, if it yields some positive change. +2.0