Mind and Iron: The Metaverse Issue with Matthew Ball

It's back. But also, it never really went away

Hi and welcome back to another shiny episode of Mind and Iron. I’m Steve Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and chief superdelegate of this very non-political convention.

A reminder that every Thursday we examine all the tech, science and general life changes coming down the pike — from a humanist perspective. We’re like Paul Skenes — all heat, no spin. But all this news and context comes at a cost. Please consider a pledge here.

We hope you had a good Fourth and enjoyed some time away; we certainly did here at M&I headquarters. Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose. And for barbecues with vegan hot dogs and good friends.

Still getting settled back so this week’s episode is a bit shorter than usual. The good news: we’ve got a super-cool topic and pretty much the smartest guest around to rap about it.

I’m talking about the metaverse. The 3D Internet. The world of spatial computing. The fancy word for the idea that we’ll all be moving around in immersive environments — living in an alternate society that, well, could it be worse than the one we already live in?

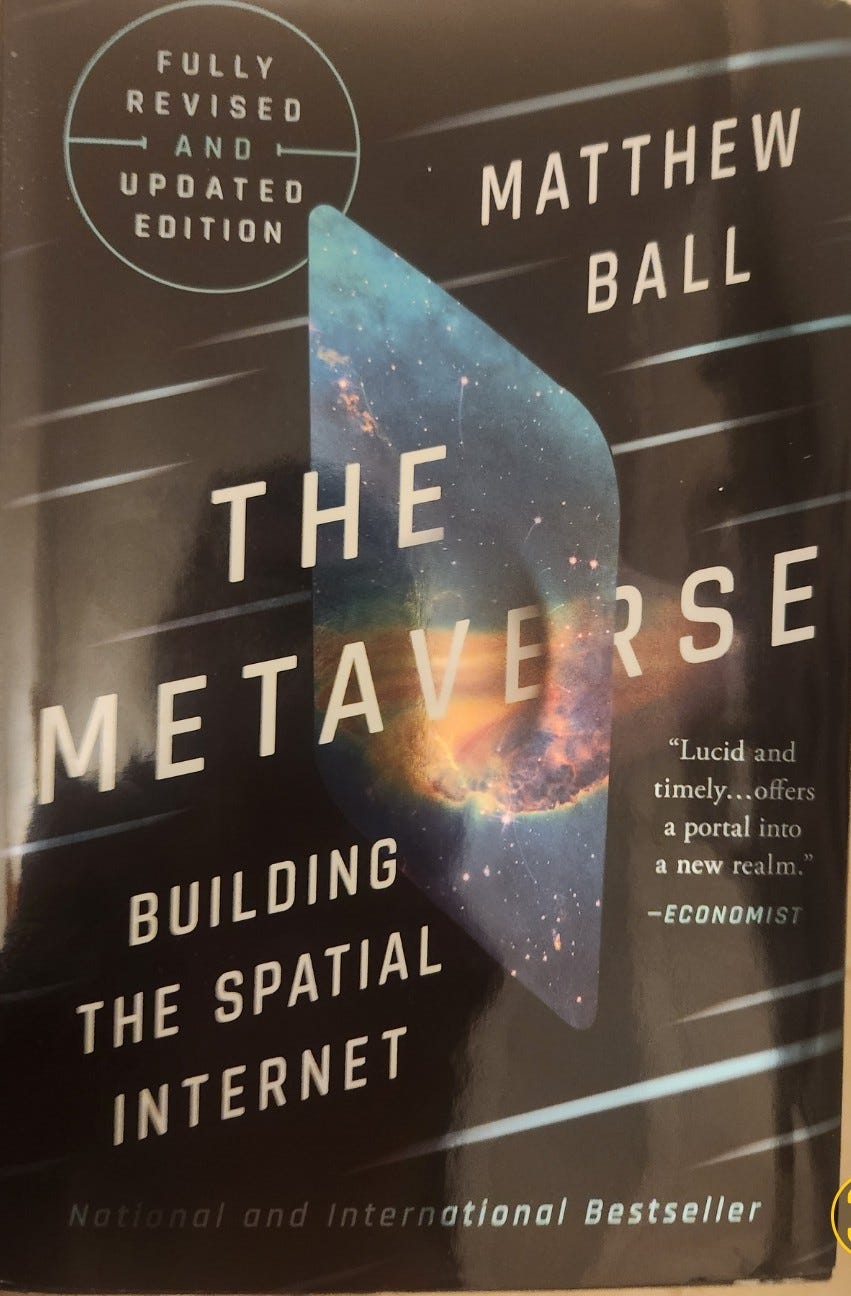

First we’ll spend a minute updating you on what’s been happening with said ‘verse. And then we’ll dive into a conversation with said smart guest, Matthew Ball. A veteran executive, analyst and expert — he once served as global head of strategy for Amazon Studios — Ball is known well to anyone who’s followed the tech and media worlds.

Ball made news two summers ago when he published the book “The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything” to acclaim from folks as diverse as Mark Zuckerberg, Tim Sweeney, Karlie Kloss and my old colleagues Gene Park and Taylor Lorenz. Now he’s about to come out with a largely new edition. Written almost entirely in 2021, the first book captured the moment as we knew it then. But the world in 2024 is different. So Ball has pretty much overhauled his tome. In our conversation he breaks down just what our digital lives may and may not look like in the years ahead.

We’ll kick off this week with a quote from him:

“All of us desperately look forward to the moment the call ends and you can exit Zoom. But when people use technologies that are functionally holographic? Everything changes. “

—Matthew Ball, master of the metaverse

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Will people still use napkins in 2030 or is this metaverse thing for real?; And, our chat with Matthew Ball

1. NEAL STEPHENSON WROTE ABOUT IT. MARK ZUCKERBERG STUMPED FOR IT. AND YOU LIKELY HEARD ABOUT IT AND WONDERED IF IT WOULD ACTUALLY HAPPEN.

Yes, I’m talking about the metaverse — that amorphous, possibly delectable idea of a fully functional virtual world that’s always on and lets us move around and socialize, learn, shop, heal, entertain ourselves and do everything else we do in real life.

If that sounds too squishy, think of it another way: The metaverse promises to take the Internet that we’re all addicted to today and build it out so that we can actually…enter it. Right now the Web is really just a series of digital tools that facilitate a physical life — Zoom calls show us all sitting in our homes, online “shopping” has us clicking on photos so the UPS driver can pull up outside and social media is often just typing out thoughts we would have otherwise spoken. The new so-called “spatial Internet” will have us living inside it — replicating meetings, browsing stores and engaging in conversations with full levels of immersion and (at least the illusion of) movement. No longer tap, tap, tapping on the glass but sitting on the other side of the window.

If that sounds at once thrilling, scary and just kind of fundamentally hazy, don’t worry — it should. It’s all of those things. So you should feel all of those feelings. The little secret is that the people creating it feel all of those things too.

The metaverse has been theorized about for some 70 years and more seriously pieced together for the last couple of decades, with everything from the more primitive Second Life in the 2000s to the early VR headsets of Palmer Luckey’s Oculus a decade+ ago. In recent years it’s taken the shape of these all-encompassing interactive entertainment platforms like Roblox and Fortnite and, most (in)famously, with Mark Zuckerberg’s grand Fall 2021 pronouncement that Facebook was a metaverse company, during which he of course also rebranded said company Meta.

But where are we with all this? Is there some new forward momentum? A quantum leap? Big change coming? Or has a hype cycle now busted, never to concern us again?

The bust part first. Numerous technological challenges abound with a metaverse— the idea of building a set of pipes capable of accommodating every possible movement and vantage point of every person using it at every point in time is so difficult as to seem impossible. (Words like bandwidth, latency and compute all rear their heads).

These aren’t small obstacles, and the amount of power and cost required to even begin to approach something that might approximate a parallel world are too gargantuan to comprehend. (Ball explains this crisply in the book, noting how even now streaming platforms need to pre-load material while video games must break up large gatherings so as not to run into these issues; imagine many people trying to congregate in real time with its infinite permutations.)

Numerous functional challenges exist too, perhaps the biggest of which is interoperability — aka, the idea of being able to move around freely without running into corporate walls. The 2D Internet, thanks to its public-interest roots, throw up no such obstacles; you can hop unthinkingly between so many different companies’ Web sites. That will be a lot harder this time. You can’t build a seamless metaverse when each company wants to create its own little universe. (One of Ball’s big points in the book: a military- and research-driven Internet at least gave it more of a fighting chance than what will be a largely corporate-created metaverse.) And if we can’t move seamlessly between worlds, why would we want to spend so much time there?

That’s the bust part. Here’s the boom part — the case for why this will happen.

Digital culture has been on an ever-higher arc in terms of both the kinds of media that dominate (from text to images to video to AI generations) and the level of immersion it entails (from email to search engines to watching video clips to losing an evening to the doomscroll). The idea of that we will be diving into a richer experience with more gusto isn’t just speculation — it’s history.

The social trendlines are also all in place for a metaverse. Escapism is decidedly on the rise — the number of people playing video games has gone from just over two billion to a good chunk over three billion while marijuana use in this country has gone up 15-fold in the last two decades. People want to get out of known modes of existence and enter other modes. The notion of an American consumer more willing to embrace an Internet that can be plunged into instead of merely skimmed — the idea of creating a fleshed-out mirror to our existence — is not just fantasy; it’s statistical.

The reality is the metaverse is slowly being built, and has been for some time. Back in the early 2010’s the first Oculus Rifts were released, making VR more plausible than ever. Around the same time Minecraft let us bring three-dimensional world-exploration into video games; in 2016 Pokémon GO went the other way and imported a video game into the exploration of our three-dimensional world. Fortnite followed the next year. Roblox has been chugging along the whole time, letting people build and live inside worlds and gaining more popularity as it goes.

The Apple Vision Pro that came out last year may or may not take off. But it is, as this list demonstrates, just the latest link in a long chain that is slowly pulling us from a physical world as we know it and entering the alternate one as it can be imagined.

True, many of these are fundamentally entertainment avenues, at least in the sense that they don’t have most of the errand-based activities that compose our real lives. But with the infrastructure thus built it’s not hard to imagine these use cases hopping the fence. Plus entertainment is how new forms of experience initially embed themselves in our lives. No one obsessed with cable news or home shopping over the past three decades thinks about how it all began with Milton Berle and Sid Caesar, nor should they.

(AI, our preferred topic many weeks, actually has a role to play here too. It will help build out the parts of the metaverse that would otherwise require laborious manual processes. And of course we can interact with AI beings in the metaverse.)

Meanwhile, small pieces of the problem are being tackled every day. One challenge of the metaverse, for instance, is that moving around in an immersive world when we’re not moving around in real life can not only make the experience less convincing but trigger dizzying disassociations. (That VR seasickness some of us are familiar with.) But what if we had “treadmill shoes” that let us walk without going anywhere, so our body actually was moving while we were in a virtual world ? A startup named Freeaim has developed just this contraption and will release a consumer model next year.

In what proportion the metaverse will be optimized for doctor visits or retail shopping, tutoring sessions or moviegoing, office-meeting or party-hanging, is impossible to know. It would be like asking someone in 1981 what the Web will be good for. We’re too far away to even define the concept, let alone understand its utility. But that doesn’t mean our lives won’t be drastically affected by it.

Also, how soon will this happen? Who knows? (Really, nobody.) But that seems a different question (and distraction) from the far more plausible likelihood that it will. Or, parts of it will. The next generation of the Internet is inevitably immersive.

Now, that doesn’t mean such a world will actually be better. The Internet in these late-stage Web 2.0 days is so often a trolly cesspool — and that’s with democratic non-corporate roots. What hope, you might ask, is there for a metaverse?

Or, put another way — if the metaverse actually happens, should we be excited about that fact? So, so many apps and platforms these days, you’ll point out, have devolved into places of abuse and provocation, not to mention mindless corporatization and commercialization, that is it really possible a grand alternate digital world will be devoid of all of that?

It won’t be. But the counterargument is that the metaverse will be large enough that it can contain these multitudes — that there will be enough people interested in civil discourse and meaningful experience that they can find their place in it too. One hardly needs to be a utopianist to believe in such a co-existence.

After all, even as the regular ol’ Internet has become a place that is populated by awfulness, many of us still find ways to derive satisfaction from it every day — transacting services, finding information, consuming entertainment and increasing our socialization. Will this new 3D Internet, whatever shape it takes, be an awful place we want to run from? Or will it be a place to give us joy, utility and even a little bit of hope? Yes.

2. WE’VE ALREADY TOLD YOU ABOUT MATTHEW BALL. HE CAN PEER AROUND THE CORNER TO OUR DIGITAL FUTURE with an astuteness like few others, without being starry-eyed about the path to getting there or the problems that await us once we do.

You should check out his book, out in two weeks. And his socials. And his Web site. I had a few questions of my own about how he sees our coming digital lives. So this week Ball and I had a (very old-fashioned and not metaverse-y) chat. The conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Mind and Iron: It's been an eventful two years since the first edition of your book came out — AI came on the scene, Meta stepped back a bit from its metaverse ambitions and of course Apple released its Vision Pro headset. What's been the biggest change to you?

Matthew Ball: Since the metaverse was named about 30 years ago we've had three different spikes — the crop of early ‘90's companies like Keyhole and Epic Games, this second burst of Second Life [in the mid-2000’s] and then the third wave that hit a crescendo with Meta's name change [in 2021]. That last wave led to the consensus that after two false starts the requisite pieces were finally starting to assemble. And we started to see evidence of that — the number of people playing Roblox on a monthly basis exceeded the entire active user bases of the PlayStation, the Nintendo Switch and Xbox. That period of 2021 and 2022 reflected the crystallization of five years of acceleration.

M&I: Then came…something else.

MB: Exactly. Then came a two-year period that Meta brought scrutiny to the expectations — multi-trillion dollar forecasts and all that came with it. Despite the protestations of many — including Zuckerberg — to say ‘this is a long-term transformation,’ everyone started to say ‘ok, when is my life going to feel that different’? We started observing this trend with renewed skepticism.

M&I: But none of this has truly slowed down, right? Many companies are still at it, whether it’s a Roblox and Fortnite building out their worlds or Google and Apple creating from their perch.

MB: Not, not at all. It just shifted back to — incubation is the wrong term, but to really significant and ongoing and yet [more limited] linear developments.

M&I: And the history suggests it won’t stop.

MB: We have to take a longer view. A consequential portion of the book is a detailed examination of how the metaverse has been built out for decades. And we see these bits and bursts when there are huge leaps and periods where development is less obvious. AI is a great parallel; it’s going through a lot of that [burst] now. We have to think about these fields as achieving different things at different times for different reasons.

M&I: Let’s talk about what it might be achieving in the next few years. In what realms do you see these metaverse making the biggest impact? I was struck in the book particularly by two examples — the oil-rig workers who can do their jobs without putting their lives in danger and the kids who can study astronomy without leaving their classrooms.

MB: I think there are a few. The first is indeed education. I’m not going to make the argument that we can ever find a substitute a high-quality first-person education. But that is not practical for many children are earth. Most children. There are not enough schools open, let alone enough funding, or quality teachers. So the experience that starts to be possible in immersive environments can be really consequential.

Another is health care — we’re now at more than 600 live patient surgeries using mixed-reality headsets. It’s proven the way this improves patient outcomes, safety, cost. They’re being done for cancer, for spinal fusion; it’s remarkable. The head of the neuroscience department at Johns Hopkins happened to perform a cancerous-tumor removal on a spine [using mixed-reality tools] and he said it was like driving a car with GPS for the first time. I love that example. We don’t use GPS instead of driving — it’s a complement, not a substitute. Do we drive faster, safer, better? That’s the test. I think we’ll see a lot of the same things once immersive technologies are used in health care.

M&I: But what’s your assessment of the larger encroachment of a metaverse? When you talking about just using immersive tools to improve education or medicine, most people get it. But when this 3D Internet means unplugging from the world as we know it and plugging into a new virtual world, people get a lot less comfortable.

MB: I always get weird responses when I talk about this topic so it will be interesting to see how your readers react to what I’m about to say. So the most common criticism that I hear is: ‘Why would you want to subscribe to a version of the future where we’re isolated from society, wearing a virtual reality headset engaged in a fantasy?’ And I don’t want that. I don’t. I actually believe the metaverse goes far beyond that, just like the Internet isn’t something we experience just sitting in front of a laptop.

But I’m also reminded that we are essentially a television culture. When you factor out work and sleep, the only thing we really do is watch television [or streaming]. The average American does it for 5 1/2 hours every day. The average senior does it more than seven hours every day. Nearly all of this is sedentary. Now, not to say something is good just because it’s better than the alternative. But the substitution of a passive and homogeneous use of time with something active, more engaged and, most important, social — which the metaverse is — seems to me largely positive.

M&I: The Internet is largely social now — or what passes for it when we’re yelling at people on X or Facebook. Do you think we should look forward to spatializing that? Is social media better when it’s more three-dimensional?

MB: I think it is. Take Zoom. All of us desperately look forward to the moment the call ends and you can exit. But when people use technologies that are functionally holographic, like Starline [Google’s three-year-old project to represent full-size humans next to us virtually], everything changes. You’re interacting with a real-time avatar, a 3D reproduction of what a computer thinks Matt and Steve look like. And the benefits of using this form of interaction are immense. We see 30-50 percent improvements in non-verbal forms of communication — hand gestures and head nods.

We also know that generally the more digital communication reproduces the real world the more moods, behaviors and other things improve. The same way we tend to have more compassion speaking on the phone versus exchanging a text; the same way eye contact allows you to understand someone’s emotional state; the same way knowing someone on Twitter makes you behave differently toward them than if they’re anonymous.

M&I: I find this argument fascinating. My assumption, like I suspect the assumption of many people, is that when you make the digital experience less mediated you increase the risk of harm from trolls and abusers; the subject is simply more exposed. But this argument holds the opposite — that there will be less trolling and abuse in the first place because many people will be dimensionalizing and humanizing the people they would otherwise target.

MB: I believe that’s true. Look, I think we should be realistic about the limitations here. I’m not someone who believes that any metaverse experience can compare with getting a hug from a loved one or going to a soccer match or having a beer at a bar with your best friend. It won’t. But that’s the wrong comparison. The metaverse shouldn’t be trying to do that.

M&I: It should be trying to create a better version of the Internet.

MB: Exactly.

M&I: Finally I wanted to ask you about MSFS — the Microsoft flight simulator that came out in 2020 and is kind of like the GOAT of all simulators — as a crystal ball of the future metaverse. As you describe it in the book, MSFS lets us fly in a world that doesn't just look like our own — it is our own. Like, you can literally shadow-pilot a plane in flight and see the same sights, deal with the exact same variables.

MB: I love this example.

M&I: I mean, it’s an incredible feat, the way they’ve re-created the details so elaborately and the way VR can plunge us into those details. (A 2D version below.) What’s compelling to me is that it points to a future in which the metaverse isn’t just a cartoonish Roblox-y or Fortniteish stylization — it looks and feels like our world. In fact it’s actually a facsimile of our world! How much will the metaverse look like that?

MB: First, when you use MSFS or stand beside someone using it you have this sensation of wonder and even befuddlement that this thing even exists. That you can fly right over your house with exactly the same weather. Or land at Charles de Gaulle exactly as a pilot would. It’s exquisite. And it's an altogether different sensation of future.

But more important I think it’s a realistic sense of the future. Of how when multiple different technological fields can come together like this — fields that are generally separate — they can build on the remarkable. MSFS allows us to disconnect from these questions of the metaverse and whether we will live like this or like that and just dwell in what a lot of this is really about — being filled with awe by an experience that we can all share.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. Last year ended with a score of -21.5 — gulp. Can 2024 do better? The first six months have been OK enough — or at least a lot better than last year. This week, we’re in…solid shape.

THE METAVERSE AND ITS PROMISES ARE STILL SIGNIFICANTLY OUT OF REACH: -3

FROM SURGERY TO SIMULATORS TO EDUCATION, THE METAVERSE CAN DEMOCRATIZE OPPORTUNITY: Big if it happens. +2.5

BY HUMANIZING TARGETS, THE METAVERSE COULD ALSO REDUCE TROLLING AND ONLINE ABUSE: Ditto. +2.0