Mind and Iron: What the Luigi Mangione Situation Tells Us About the Future of Several Kinds of Tech

A special edition on the gun, the face, the algorithm

Hi and welcome back to another snazzy episode of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and lead curator at this newsy art gallery.

Every Thursday we come at you with all manner of content on tech, AI and the future — and how we can build a more human one. Please consider supporting our independent mission.

We'll hit you next week with our end-of-year programming. This week, we're taking a deep dive into the alleged killing by Luigi Mangione of UnitedHealthcare chief executive Brian Thompson and all that it points to.

Tech has been draped all over the story this week, from the facial recognition that (almost) aided in Mangione’s capture, the 3D-printed weapon recovered on Mangione upon his arrest and the algorithms at the heart of UnitedHealthcare that may have triggered his rage. So we’ll take each topic and unpack it carefully to see where we are and where we’re going.

First, though, the future-world quote of the week:

“If this algorithm spits out 16 days for [a patient] and they’re not ready to go home on the 16th day, if they can’t even go to the bathroom themselves, if they still can’t walk around but the algorithm says it’s time to ship them out, that’s where it’s a problem. And that’s what’s happened.”

— Health-care journalist Bob Herman on how the algorithms of UnitedHealthcare deny deserving people care

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

THE SURVEILLANCE:

It was funny to read headlines that technology played little part in capturing the suspect. Headlines like:

And sentences like (from the same NYT story):

"In the end, it was the simple act of distributing photos — not sophisticated facial recognition technology — that led the police to a man they are calling a 'person of interest' in the fatal shooting of a health care executive in Midtown Manhattan last week.”

As if ubiquitous cameras didn't capture images of the suspect at a Starbucks, the hotel-based site of the killing and at Port Authority attempting a getaway — and digital platforms didn't allow all those images to proliferate .

Each one of those of course made more likely something that might otherwise not have been possible: an employee in a Western Pennsylvania McDonalds being able to spot him. Saying technology played no role in Luigi Mangione's capture would be like watching the nurse giving you orange juice in the recovery room after surgery and saying advanced medicine had nothing to do with your healing. How do you think you got to a recovery room in the first place?

And given that the number of surveillance cameras is growing — they've nearly doubled over the last decade to at least 85 million, one for every four Americans — technology’s ability to spot any of us is growing too. For better, worse, indifferent.

But let's set that aside and address only the potential of the most cutting-edge technology: the facial-recognition kind. It's true, it couldn't spot him. And the question is why.

Or, maybe the more pertinent question — how soon could it?

Here's the nugget you need to know: AI-based facial recognition didn't play a huge role not because it wouldn't have been good enough on its own. It would have — any head-on facial photo of a suspect is generally enough to narrow down the possibilities (there was some debate over whether the photo of Mangione qualified).

The tricky part is what comes afterward. What you need for facial recognition to be effective is not the recognition part — it's the ability to compare it to other faces. That is, the key here is the depth of the database that you’re accessing. Because every state's DMV is run separately, and because local and state police databases are a patchwork of jurisdictions and levels of polish, this part of the equation becomes much more slippery. (Not to mention the massive Constitutional problem with connecting all of this, as a number of ACLU lawsuits make clear.)

The biggest hindrance to a system that would allow for clear identification of a person of interest isn't the tech — it’s a massively interconnected system with all the necessary faces stored in it.

Those with incentive or means to build such a system have decidedly made progress. Already facial recognition is in widespread use at airport customs checkpoints in the U.S., as anyone who's not had to pull out their passport in the last couple years knows. Border-centric government agencies are incentivized to use biometrics because they think it's safer (and have the money to try it).

Local police departments, shopping chains, schools, hospitals and other institutions are often less well capitalized and less motivated, which is why your local Big Box retailer or emergency room doesn't recognize you by your face when you come in the door — yet.

Because here's the reality. The tech has been moving forward — in fits and starts, but moving still — across a whole bunch of realms.

The NYPD has been deploying facial-recognition technology for years. Banks in the past few years have quietly used the tech as a presumed safer alternative to your PIN (inserting your card in an ATM or teller machine may soon be a quaint anachronism). Macy's uses it. So does Fairway. Malls are ramping up.

If supermarket loyalty programs years ago asked us to give up our address and purchase-history data in exchange for saving a few bucks on a six-pack of soft drinks, facial recognition will ask us to hand over a lot more.. Hopefully for better incentives than the six-pack.

I don't know that we'll all be pitched ads based on retina scans walking down the street, “Minority Report" style. But the idea of being able to simply opt out will get harder. The history of the data-services bargain of the past couple decades is a perk that starts as a luxury soon becomes a necessity, and what we initially thought twice about giving away we forgot we ever possessed in the first place. (And the idea that it will only be used for shoplifters and security seems…unlikely.)

Schools are starting to use facial recognition, too. And if you think it's just to monitor for potential guns and other security threats, think again. The big push is for classroom management — software that can detect inattentiveness. Zoning out during class used to be an acceptable evil for teachers or even a positive for kids who can benefit from daydreaming time. But there’s no problem tech firms can't quantify and reduce to a data set, and so even something as mundane and private as our facial expression in a classroom becomes a target of its intrusions.

As one new system recently chronicled by Inside Higher Ed has it, "Multiple cameras spread throughout the room will take attendance, monitor whether students are paying attention and detect their emotional states, including whether they are bored, distracted or confused." Who needs Michelle Pfeiffer to motivate those minds when a surveillance app could just give them a digital shove?

Every day that goes by increases the chances that any of us are identified and assessed based on simply showing our face and interacting with the ever-greater number of touch points that use this recognition technology.

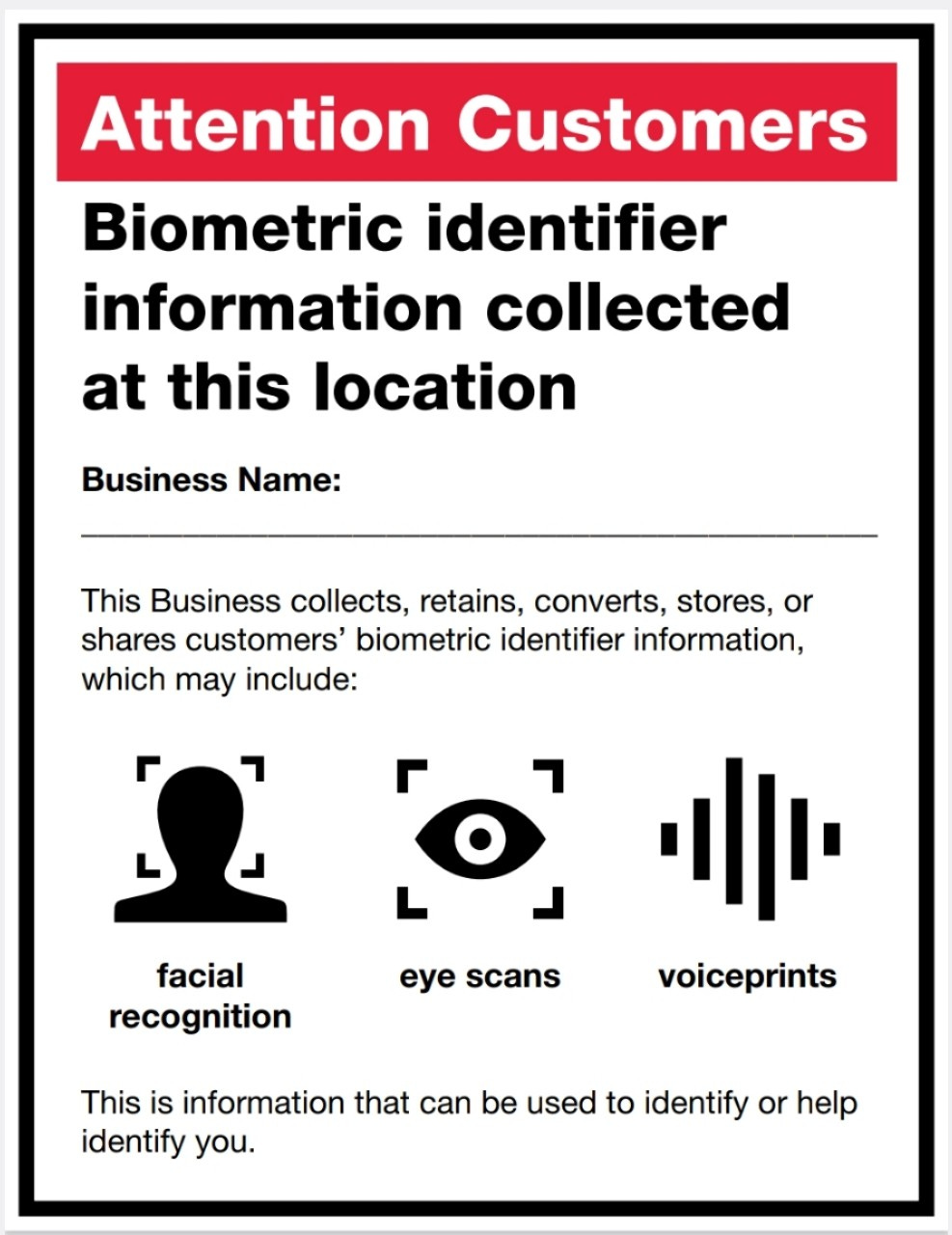

New York City passed a law that at least required stores to disclose if they’re using the tech; you’ll see signs like these. I don’t see anyone hiding their face as a result.

There is obvious concern here on bias grounds. Major problems attend facial-recognition software itself, not least that it makes far higher rates of mistakes with people of color and nonbinary people, to name a few. And there is concern on privacy grounds — on the simple matter of being able to go about our lives without knowledge so intimate captured by technology so present, then weaponized accordingly.

In one of the most notorious — and bonkers — cases, Madison Square Garden has spent at least the last two years deploying facial recognition on its security lines to spot any lawyers who works for a firms suing the company and banned them from entering. Like, literally, they’re just turned way by the algorithm when they show up for a Knicks game. Jim Dolan, always on the cutting edge of creepy.

All of this will move forward at different rates of speed depending on the geographic area, the public appetite and the economic realm in question. Overall, though, the trend is forward. Some states are starting to push back — New York has a ban on using facial recognition in public schools — but plenty of other municipalities are pushing forward. We are standing on the brink of new adoption pushes and counter-pushes — of a new frontier in the privacy wars. And we know who usually wins those.

Facial recognition may not have identified Luigi Mangione, and that fact gives many of us worried about its potential intrusiveness a decided sense of security. “Humans at McDonalds: 1, Computers: 0,” we might think.

But the game is just beginning. And facial recognition, like so much of new tech, knows how to run up the score.

THE GUN:

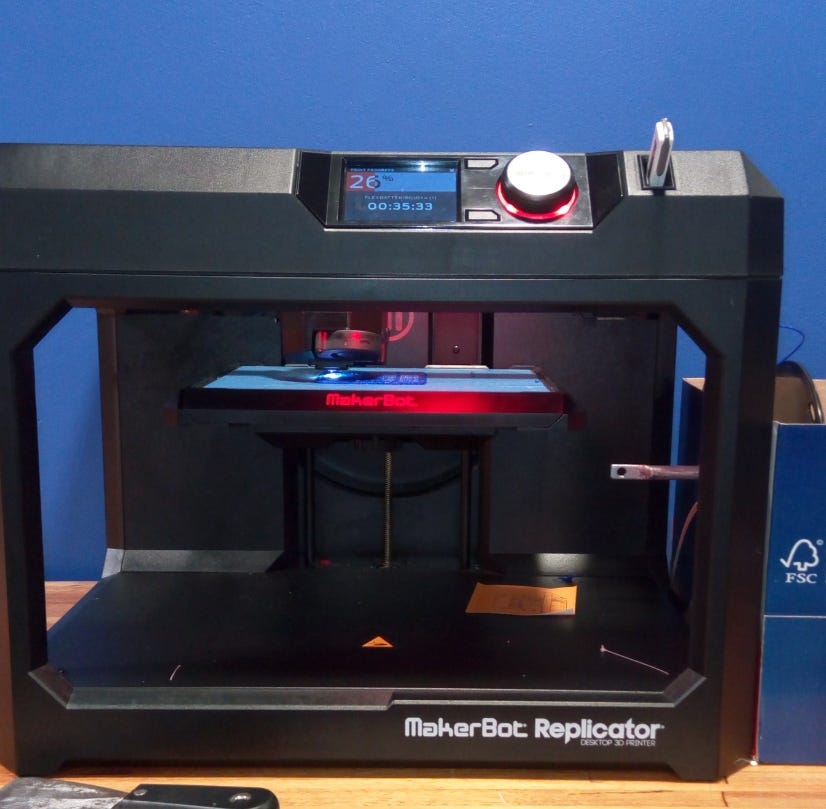

There has been plenty of talk about the gun allegedly used to kill Thompson, which appears to be of the 3D printed variety. The gun “may have been made on a 3D printer,” said New York Police Department Chief of Detectives Joseph Kenny, flat-out.

A 3D printed gun is what is sounds like, with the materials that are fed into the machine used to construct a weapon instead of a cake or your kid's 6th-grade art project. (Designs are downloaded from the Internet.) Essentially there are three types, ranging from the most start-from-scratch model that employs pretty much no outside parts to the innards of a traditional firearm for which the printer simply makes the frame. The gun recovered in the Thompson case was the last kind.

Several years ago it was trendy in future-y circles to marvel at/wring hands over 3D guns. The idea that a full-on serviceable weapon could be literally concocted at home with the help of a machine you buy for a few hundred bucks on Amazon and a design you download from the Internet was eye-popping enough to merit attention. Chatter has been quieter of late — until last week.

Mostly 3D guns haven't caught on in the U.S. because regular guns are so freely available. Hobbyists and bespoke types have dabbled in it, but even the most minimal construction requires a decent amount of know-how, and why bother with that when buying a firearm is so easy?

That is, assuming it is easy for you. The big advantage (if you're trying to get away with something) to a 3D gun is that it does not require any kind of license or background check, which makes it a lot more appealing for someone who might otherwise have trouble walking into a gun store and making a purchase. What's more, a 3D-printed gun can't be traced — it's by definition a ghost gun since you didn't acquire it anywhere and the components are untraceable. (There are some exceptions but this is usually true.)

Ghost guns are homemade guns of all types, and for years mostly came into this world via online kits sent to people's homes. ("Privately made firearms (PMFs) are firearms that have been completed, assembled or otherwise produced by a person other than a licensed manufacturer," is how the ATF defines ghost guns, also known as PMFs.) But since new federal rules went into effect two years ago requiring that components in these kits contains serial numbers, ghost guns are more and more likely to be of the 3D-printed variety.

It's not fully clear why a suspect without a criminal record would go through the trouble of using a 3D gun, as Mangione allegedly did here, but for someone who had little experience buying guns and plenty of experience building stuff, it might actually be the easier route to take. Also, the untraceability would be a virtue if you were planning ahead and wanted to make it a little harder for law enforcement to track you if they recovered the gun. (That of course turned out to be moot here, but that would be the thinking.)

So how big an issue are 3D-printed guns? Is this something we need to be concerned about given how it might make someone contemplating a crime less afraid of getting caught or simply put guns in hands that otherwise couldn’t access them? And given that more than 48,000 people in the U.S. are already killed by firearms annually?

The number of ghost guns recovered by law enforcement has gone up stunningly from 2,000 to 20,000 between 2016 and 2022 according to the ATF and DOJ, and while some of that reflects the fact that loopholes have reassuringly been tightened on traditional guns, overall it's not a great sign that so many untraceable ones are now flooding the streets.

The key timeframe to watch in terms of the growth of 3D guns will be the number of ghost guns after 2022 (comprehensive data hasn’t been released yet), since that's when the serial-number requirement went into effect. If the number drops off drastically from the 20,000, 3D printed guns aren't the major factor we thought they were. If a similar number of ghost guns wound up being recovered in 2023 or 2024 or if the number even rose, we got a real 3D problem on our hands. And with printers getting cheaper and materials getting better….

The solutions to regulating 3D guns are limited. Most of the parts are not illegal on their own, and a printer at home is not something one could or even want to regulate. Some kind of restriction could be attempted with the instructions, but as the swirl over “The Anarchist's Cookbook" 50 years ago showed — the FBI famously concluded that the homemade-bomb guide does not urge “forcible resistance to any law of the United States" — trying to stop the flow of know-how for a homemade weapon won't get very far. (Good discussion on the issue here.)

It may simply be that the technological era we inhabit builds in a certain amount of danger that can't be controlled. Trying to stop people from printing guns comes with too much collateral damage in also stopping them from printing everything that’s perfectly legal. Our future may simply be one filled with a glut of these weapons. But don't worry — there's always facial recognition to omnisciently see who's carrying them.

THE ALGORITHM:

Less than three weeks before United chief executive Brian Thompson was killed, ProPublica published a story with this headline: “How UnitedHealth’s Playbook for Limiting Mental Health Coverage Puts Countless Americans’ Treatment at Risk.”

That playbook is anchored by an algorithm used by United subsidiary Optum, which in one eye-popping case after another has been alerted by said algorithm that mental-health counseling is unnecessary — then had staffers call therapists telling them they’ve ordered too much treatment for a given patient (even when the therapists say everything they’ve done is standard). Often Optum winds up denying the claims no matter how the therapist insists they’re legit, exactly the kind of situation that seemed to anger Mangione.

Clearly such plans are helping the company save money — Fortune lists UnitedHealthcare as the eighth most profitable company in the world. Whether it’s helping any of the patients is another matter.

California, New York and Massachusetts have all taken measures to prohibit these practices — including the New York AG winning a big settlement from United for the tens of thousands of people affected by the United mental-health denial — but their reach is limited to their jurisdictions.

Algorithms and other forms of AI are of course increasingly used in a host of applications where screening is necessary and humans are either too few or too subjective to make the determination. Bank loans are one high-profile use case; college admissions are another. Basically if an institution has to determine if you’re worthy of its scarce resources, AI is a way to streamline the process and ensure that the right people are granted the privileges.

This is not inherently bad. While machines making decisions about whether you could buy that house or get reimbursed for that surgery give off some serious heartless optics, in theory it shouldn’t have any negative consequences. Assuming the amount of money or admissions slots is fixed, the AI isn’t shortchanging anyone; if anything you might argue it’s making better decisions that will ultimately benefit users. (E.g., if a lending bank’s AI chooses higher-quality loan candidates than a human would, the bank gets paid back more, is more likely to stay solvent, and more likely to keep lending out money.)

In theory.

The problem is it’s just that: a theory. In reality there’s little evidence so far that the AI is making better decisions on these loans. Institutions after all aren’t using it for that reason — they’re using it because it a) saves them money on hiring human screeners 2) gives them an illusion of effectiveness, which may help them when going to their boards but doesn’t actually lead to better results.

Health care is uniquely ill-suited to algorithmic decision-making because a person’s treatment and recovery are highly subjective and require firsthand personal examination — a patient’s computer-fed data may not tell the whole story — and because the stakes are so damn high if a judgment is off base. As the health-care journalist Bob Herman told the Vox podcast Today, Explained on Tuesday:

“So let’s say someone goes to the hospital and then the hospital says, okay, you know, you’re ready for physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy; let’s send you to a rehab facility or a nursing home. So a person will go there and they’ll start their physical therapy, and behind the scenes, UnitedHealthcare has used a tool called NaviHealth. There’s an algorithm within the company that looks at the patient’s demographics — how sick they are, their history — and tries to come up with some kind of prediction of how much time they’ll need in that nursing home. Let’s say it’s 16 days. That’s what the algorithm says — after 16 days, you should be good. Now, if it’s used as a guide, that’s fine. But in many cases, we found documents that said that United told their case managers, ‘You have to stick to the algorithm.’

“And that’s where it becomes a problem, because if you’re saying this algorithm spits out 16 days for somebody and they’re not ready to go home on the 16th day, if they can’t even go to the bathroom themselves, if they still can’t walk around but the algorithm says it’s time to ship them out, that’s where it’s a problem. And that’s what’s happened.”

Machines have a role to play as first lines of defense in screening applicants for limited resources. But too often they become an inflexible arbiter that their human overseers are institutionally prohibited from reining in. More important, they can get inflated into something humans don’t want to rein in; the overseers have been too conditioned to regard them well to do that.

The Princeton neuroscientist Molly Crockett and Yale anthropologist Lisa Messeri published a paper in Nature this past March breaking down the ways we go wrong in endowing machines with power they don’t deserve — “AI as Oracle,” “AI as Arbiter” etc.

“These tools are being anthropomorphized and framed as humanlike and superhuman,” Crockett told Scientific American when the study came out. “We risk inappropriately extending trust to the information produced by AI.” This is true even when the AI is far from that — when it’s hallucinating (but in a black box so we don’t even know that it’s doing it) or when it’s fed really bad or biased data (which, unlike with a human decisionmaker, we can’t interrogate).

When it comes to health insurance, these machine systems are viewed with divine-like reverence by executives because they see any way to sort through a pile of complicated claims as a godsend. For the millions of people who find themselves bankrupted by necessary procedures or made ill when they now can’t afford to get them, the algorithms look a lot more like the devil.

The month prior to their health-insurance algorithm story ProPublica published another piece that was equally eye-opening, about EviCore, a product owned by Cigna and used by United and many other insurance giants. EviCore’s job — its raison d’etre — is to determine who gets reimbursed, which is a far too polite way of saying who doesn’t get reimbursed.

"[It] makes money by turning down doctors’ requests for payments, known as prior authorizations,” the nonprofit journalism outlet wrote. “Call it the denials for dollars business.”

The story is full of moments from doctors and former AMA presidents tossing out quotes like, “They love to deny things.”

In fact EviCore says the quiet part out loud, marketing itself by “promising a 3-to-1 return on investment — that is, for every $1 spent on EviCore, the insurer would pay out $3 less on medical care and other costs. EviCore salespeople have boasted of a 15% increase in denials.”

At the heart of EviCore is an AI tool insiders call “the dial,” and its ability to turn down claims is nearly as easy as turning down one. Essentially, the algorithm can be adjusted to greater levels of strictness that would turn down claims that would otherwise be approved. (They use a more workaround-y method, but it basically comes down to this.)

And therein lies perhaps the biggest problem with algorithmic health-insurance: it can be manipulated. If you were an insurance company in the pre-AI age and wanted to turn down totally legitimate claims en masse, you’d have to issue a companywide directive and try to get all your employees and adjusters to implement it, hoping that none of them have humanity, a sense of fairness, or any of those other pesky attributes that might stop the swiping of money from sick people.

But if you rely on an algorithm, you simply turn down the dial. No sticky resistance; no messy need to get those free-thinking humans on board. And if anyone complains, you just throw up your hands and say “The machine never lies.” Of all the anthropomorphic guises Messeri and Crockett list, they may have neglected the most dangerous one: “AI as Scapegoat.”

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. Last year ended with a score of -21.5 — gulp. Can 2024 do better? It’s been that way so far. But we can’t sugarcoat it: this week is bleak.

FACIAL RECOGNITION WILL SOON MAKE ALL KINDS OF CLAIMS ON OUR DATA, WITH QUESTIONABLE RETURNS: -3.0

UNTRACEABLE 3D GUNS ARE PICKING UP STEAM: -2.5

HEALTH-INSURANCE ALGORITHMS SCREW US OVER: -3.5