Mind and Iron: What Will it Mean When Woolly Mammoths Again Roam the Earth?

Also, what AI experts really think the future holds. And the argument for machine-generated movies.

Hi and welcome back to another spicy issue of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, senior editor of tech and politics at The Hollywood Reporter and lead baker at this newsy matzah factory.

Every Thursday we tell you what's happening across the world of tech, science and business and the type of future it points to, with all of the context and none of the spin. Please consider supporting our independent mission.

It's been another hectic week in futureland. First, those dire wolves (name not designed to placate the anxious). They are making howls that haven't been heard on this planet for 10,000 years. Is that sound a serenade or a warning?

Also, the man who canvassed all those AI experts talks to Mind & Iron — with some extremely eye-opening conclusions about where the world’s greatest thinkers believe we’re going.

And the future of AI in media is racing ahead faster than ever.

First, the quote of the week:

“If we want a future that is both bionumerous and filled with people, we should be giving ourselves the opportunity to see what our big brains can do to reverse some of the bad things that we’ve done to the world already.”

— Colossal's chief science officer Beth Shapiro on why resurrecting extinct species is a good idea

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Deconstructing de-extinction; AI’s new digital gap; when visions become instant movies

1. THINK OF THE SCIENTIFIC WARNINGS OF "JURASSIC PARK" and you might focus on the end of an Ian Malcolm soliloquy, when Jeff Goldblum leans in and says with great import, "Yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn't stop to think if they should."

A nice line. But I've always been taken by what comes a minute earlier, when Malcolm first starts pushing back on the creators of the dinosaur theme park. "Genetic power is the most awesome force the world has ever seen," Malcolm says. "But you wield it like a kid who's found his dad's gun."

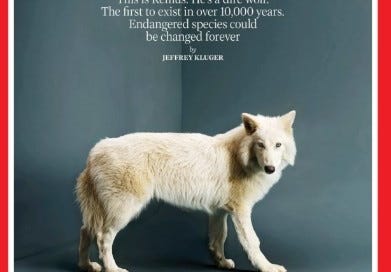

All of that came to mind this week with the Time story on dire wolves. Everybody and their clone-mother has an opinion about the three canid pups given their Dolly-esque moment on the cover of the magazine this week.

If you've been too busy (or just too scarred by your childhood viewing of Jurassic Park) to pay attention, the upshot is this: The dire wolf is a creature that once roamed the Americas freely but went extinct thousands of years ago. Now Dallas-based biotech firm Colossal has made a bunch of mutations that have brought them back.

Scientists extracted the DNA from dire wolf remains, figured out what it looked like, and then rewrote the code of the (still very much around) gray wolf so it had all the mutations of a dire wolf. (Only about 20 edits were needed.) Then researchers implanted the ovum of what they created in a dog so it could gestate, yielding these three dire wolves. (Don't think too much about what was flashing through the mind of that dog giving birth to an extinct wolf; it could bring different movie flashbacks, the kind involving Sigourney Weaver.)

Colossal has been keeping these three lupine pups at an undisclosed wildlife facility, marveling at the reality of creatures that, as chief animal officer Matt James says, provides "shocking, chilling moment[s].” To wit, "These pups were the first to produce a howl that hadn’t been heard on earth in over 10,000 years," per writer Jeffrey Kluger.

A lot more is going on here than some cute animals on magazine covers and Crichtonian theme parks (theme parks aren't a part of it at all in fact). What Colossal has done is either one of the most important or most silly or even most dangerous enterprises you'll find, depending on who you believe.

Co-founded by the MIT biotech pioneer George Church (he was a key member of the initial CRISPR team), Colossal has an ambitious goal — reintroduce extinct and endangered species to their natural habitats to create richer ecosystems/restore balances thrown askew by climate change and human activity. Basically, Colossal wants to use the microbiologic tools developed for medical purposes to solve a big environmental problem.

That's the idea behind Colossal scientists' efforts with the dire wolf, as well as other projects involving the woolly mammoth, Tasmanian tiger, dodo bird and others. Last month the company announced it had produced a "woolly mouse" — essentially a half-step to bring back the mammoth, but as a mouse.

“If we want a future that is both bionumerous and filled with people,” Colossal's chief science officer Beth Shapiro says in the Time piece, “we should be giving ourselves the opportunity to see what our big brains can do to reverse some of the bad things that we’ve done to the world already.”

Such a plan has certainly attracted many top scientists (scores work for Colossal) and plenty of investors (funding is at $435 million and counting) in its bid to revive these extinct species.

Whether Colossal can do this, and whether doing so would accomplish anything good (or avoid accomplishing anything too bad), is the subject of fierce debate.

For starters, there's a question of whether they’re even doing what they say they’re doing. Despite all the hype about their creations, what Colossal has often engineered is skepticism. Are they really saving the world from extinction? Or just creating more biodiverse designer dogs? In what has to be the ultimate scientific mic-drop, the German genome engineer Stephan Riesenberg offered this to the news of the woolly mouse last month. "[Colossal] is far away from making a mammoth or a 'mammoth mouse.' It’s just a mouse that has some special genes.”

The debate raged on science reddit this week with the wolves announcement too. Is this a scientific breakthrough? Or just a gene-editing-enabled parlor trick?

But even stipulating that Colossal did pull off a lupine resurrection doesn’t really resolve the argument.

First, there's the matter of keeping the animals in captivity, which is both limiting to the animal and not an indicative experiment; a dire wolf kept on a nature preserve with two companions may tell us very little about the true return of the dire wolf, which in nature hunts across many miles with an entire pack.

Also, critics have pointed out that the better way to stop species from going extinct is to, you know, not kill them off in the first place. Instead of devoting resources to bringing back the long-gone, we should be committing efforts to maintaining the still-here.

Most consequentially, there's this: Introducing species into a new environment can quickly go south. The law of unintended consequences often means bad outcomes even for natural species. The introduction of cats to control rodents, for instance, has often led to the unwanted result of numerous birds killed, habitats destroyed and ecosystems upended. And those are known creatures, not genetically modified beasts whose full habits remain a mystery. Nature was honed over millions of years of evolutionary biology — creatures and ecosystems forming food chains and careful balances (that are then upended by humans). What disruptions lab fiddling will effect is anyone's guess.

And yet to say that none of this is productive is to deny both the history of science and the needs of the earth and all of us who occupy it. The general fact is that, for all the fears this leads to a scenario in which we must be rescued by Laura Dern and a friendly Tyrannosaurus, the impulse to swing big to solve a problem is also what brought us antibiotics, the X-ray and cutting-edge cancer research.

The more specific fact is that too many species have been too badly ravaged for modest solutions. Sure, it would be nice if we had a time machine and could stop all that. But even the most ardent activist will admit that pure conservation efforts won't prevent tens of thousands of species from going extinct, and in this light the argument a Colossal makes for redeeming some of them isn’t unpersuasive. As Shapiro says, "We do not argue that gene editing should be used instead of traditional approaches to conservation, but that this is a ‘both and’ situation." If nothing else, their gene tweaks may help us understand why certain species are going extinct and what can be done to prevent it.

And besides, would it really matter if we did oppose this? A different Ian Malcolm line comes to mind. "If there is one thing the history of evolution has taught us is that life will not be contained, life breaks free it expands new territories and crashes through barriers painfully maybe even dangerously but there it is."

That’s true of various animal species. But it's also true of the human species looking to understand and guide them, a species that itself tends to crash uncontainably through barriers to see what happens. In the end, we simply don’t know what genetically modifying creatures to act like a mammoth or dire wolf will lead to. Which is exactly what will make us do it.

2. WHEN IT COMES TO KNOWING WHAT OUR AI-ENABLED FUTURE HOLDS and what effect it will have on our humanity, we’re all stumbling around in the dark. No one really knows anything. But a raft of experts stumble a little less.

Last week we told you about a study that Lee Rainie's Imagining the Digital Future Center at Elon University in North Carolina conducted with hundreds of AI experts. The questionnaire asked them to evaluate the likely effects of AI on humans. It yielded some very compelling findings — for instance, respondents believed that AI will have a positive effect on three core human traits and a negative effect on nine of them.

Many of the experts wrote essays too, all under the wide-ranging and possibility-laden rubric of “Being Human in 2035.”

This week, we talk to Rainie about what he learned. If you're not familiar with Rainie, he spent nearly a quarter-century at the esteemed Pew Research Center leading studies on tech and its effects. He and his team literally produced more than 800 reports in that vein. (At The Post the data team basically treated Pew as the holy writ of polls, and rightly so.) When it comes to getting to the root of what people feel about tech and the future, Rainie's our man.

We had a fascinating conversation about the potential effects of AI on humanity (and on our humanity) — including the widening of a social gap that goes well beyond the financial and how models could turn us all into Wall-E. Here's an excerpt of the chat, edited for brevity and clarity.

Mind and Iron: You've conducted one of the most comprehensive studies yet of experts and their AI predictions. What struck you immediately?

Lee Rainie: Our study is weighted toward academics, critics and technologists who are more likely to be worried about the future. Whenever I have a group like this I expect it to lean to the negative. So what was most interesting to me was the positive — that they believed AI can be helpful in key areas like creativity, curiosity, and capacity to learn. As language models have come to prominence there’s been so many questions about how it’s intellectual-property theft and dampening creativity. So that was good to see.

M&I: Why those three characteristics, do you think?

LR: If you think about them, they’re all qualities associated with leaders, with how we relate to others. Where many of the nine negatives [including mental well-being, empathy, sense of agency and sense of identity] are more internal; they’re how you think about yourself. Those are more of an exercise in imagination. They’re not a practical version of applied external human life.

M&I: So it's almost like they believe AI can help us save people but hurt what kind of people we are.

LR: Once you get to the essays those are the concerns you see. “Yes, AI can help us. But it might make people feel demoralized or obsolete.”

M&I: Another distinction between those categories is that one set of traits involves a kind of deep, philosophical sort of thinking — what’s my identity or where does my empathy lie? As opposed to something like curiosity, which is a lot more improvisational.

LR: It feels a little like Daniel Kahneman’s whole approach of System 1 and System 2. (basically, instinct versus hard analysis). AI is going to help us get better at System 1 because it’s good at that. Not so much System 2.

M&I: That fits with a lot of our experience with Generative AI — it sort of can very quickly size something up but not really have a deeper level of understanding about what's happening.

LR: Yes. That’s why it’s good as a ground element or raw material to get juices flowing. Or why it can remind you of what there might be to know in an area. But making connections you hadn’t thought of — that jolt, that spark of creativity that almost comes unbidden — that’s something it can’t do.

M&I: How will that play given that people themselves have very different aptitudes on this? I can’t help feeling like AI is going to widen what you might call the creativity gap — that for all the talk about how it levels the playing field what it will do is highlight even more the gulf between the few people who can achieve a kind of originality of thought and all the rest of us who it only seemed could until a machine came along and we realized we couldn’t.

LR: That’s exactly what’s going on in the framework many of these experts applied. Some people are smart and creative and literate and they will feel like royalty in a world where they can do what AI can’t. But the vast majority of us are not in that rarefied group. And that’s the crowd these experts are worried about. They’ll get demoralized because they can never hope to improve on the palette in front of them.

M&I: And it could create all these new rifts.

LR: Absolutely. You get the strong sense from the responses that a lot of social divisions and economic divisions are going to flow from this. There’s going to be a small crowd of very original people, and they’re going to be in fine shape and this will be a wonderful moment for them. Then there will be everyone else.

M&I: It’s interesting we talk about AI as potentially fueling curiosity. It seems like the reverse could be true — if the Internet made us work to go find stuff out, AI will do the opposite, spoonfeeding it to us to such a degree we’ll stop wanting to seek out knowledge or even know how to do it.

LR: There’s an expert from Denmark named Alf Rehn who describes this exact worry [in the report]. People will be so satisfied with what comes out of the machine that they won’t even try; they’ll worry they look dumb if they try to act enterprising at all. He says that AI will become a “mediocrity engine” — basically the information we get will be lacking in all spark and creativity. And people will just accept it without trying to learn anything new.

M&I: A kind of intellectual Wall-E, basically.

LR: There’s a wonderful quote that the way the world is going we’ll experience too much “Wall-E” and not enough “Incredibles.” We’ll get too many intellectual empty calories and not enough nutrition.

M&I: A scary thought.

LR: The other part that makes it bleak is the messiness of human behaviors, that the only way to get better at stuff is to fight your way through it, all the false starts and the dumb ideas that don’t work out. Will we still do that?

M&I: Plus the social equivalent, of learning how to deal with different or difficult people. As the futurist and researcher Nell Watson asks — what happens when we can program our friends?

LR: What’s risen in these last years [with social media isolating us] may just be a harbinger and it’s going to get much worse. AI arrives at a point in time when what we look for in life to make meaning is in decline. Religion is in decline; community is in decline. Tribes too — all these things are withering to some degree. And now you have something that can really foster that sense of purposelessness.

M&I: I guess we got to some of the negative after all!

LR [laughs]: We did. But the exports weren’t all dystopian. There was utopian ways this could break too. A lot of new social and economic realities are on the table. The idea of co-learning and co-intelligence may really allow us to make smarter decisions, at the individual and the collective levels. We will be relieved a lot of very crappy work, so we should be able to take care of ourselves because we’ll have a lot more time to do it. A lot of stuff will be taken off our plates. But the comma after that is that the darker side could not be clearer — dependency, demoralization, giving in to the machines.

M&I: I’ve never felt so hopeful and so despairing.

LR: I think a lot of the experts would agree.

3. FINALLY THIS WEEK, I JUST WANTED TO NOTE something I reported over at THR. Last week we told you about Justine Bateman and her deep skepticism for what entertainment companies are doing with AI.

This week I talked to the people who run said companies doing said things with AI. Specifically, the head of creative at Runway, one of the leading content-centric AI companies, and EDGLRD, the production company of "Spring Breakers" director and general digital boundary-pusher Harmony Korine.

Runway executives and EDGLRD have just signed a deal to formally work together (the upshot will be a lot more AI-fueled art) and I was curious as they made this deal why the principals thought that AI won’t just be a turgid rehash but actually fuel creativity — why Bateman is wrong.

Here's what Runway creative chief Jamie Umpherson and EDGLRD's chief commercial officer Alon Soran said on the topic. We'll let their words, for today, be the last ones.

Umpherson: “The really exciting opportunity for someone like Harmony is the way he approaches media and formats and story structures in such a novel way...You can begin to do things you just couldn’t do before — impossible things.”

Soran: “I know a lot of people are afraid of it but what this tech enables you to do is take anything inside your brains and bring it to life immediately. For the first time our ability to make things is at the same pace of our ability to think of them. I think that matching pace is going to break the floodgates open.”

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. This year started on kind of a good note. But it’s been pretty rough since. This week? Not as awful.

REHABBING SPECIES IS A DESPERATE IDEA BUT WE’RE IN DESPERATE TIMES: +2.0

A NEW AI CREATIVITY GAP AND THE POSSIBILITY OF A WALL-E-IFICATION OF SOCIETY: And a couple positives. -2.5

Wonderful column! Some of the things that you quoted from Jurassic Park reminded me of a bioethics course I took several decades ago. It was a discussion regarding the downfall of all great civilizations. The consensus was that for America, we definitely have the brilliance to do amazing things but don't have the wisdom to do them properly.