Mind and Iron: You want to know the next president? Ask an AI

A polling mind-scramble. Also, the future of warfare is drones that collaborate like people.

Hi and welcome back to another sparkling episode of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and head RA of this newsy campus dorm.

Every week we bring you the best of science and tech, shedding light not only on what's happening but what we should want to be happening. We're completely independent. And aim to stay that way.

We’re coming at you early again this week, with a quick caveat that we may or may not publish next week in honor of Halloween (and some other schedule over-crowding). TBD. If we don't, we're back at you the following week, in a post-election news landscape that is sure to be super-quiet and uneventful. 😬😬😬

Lots has been happening out in Techland these past few days, including a computer that can do the computing (or at least the searching) for you, courtesy of OpenAI better-health alternative Anthropic. Newsletter-monger Casey Newton over at Platformer has a good take.

For another time. This week we're focusing on two topics, both fittingly in the politics realm. The first involves polling — namely, why does it stink? But also, is there a way to do it better by not asking people at all — by asking machines? So believe a couple teenagers (really). And they may be on to something.

In a decidedly more...aggressive context, we've written about autonomous weapons before, and how there are, ethically speaking, perhaps a few benefits along with all the justifiable doom. But what happens when these weapons don't just fly autonomously with some smart programming but actually react to and communicate with each other? Those are called drone swarms. And, ready or not, they're coming over the horizon.

First, the future-world quote of the week.

“There are massive issues when you’re using real people. You never know if someone is telling the truth.”

— AI pollster Cam Fink, on why we should start asking machines who they’re voting for

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

A better way to figure out who'll be president?; flying fighting machines that talk to each other

1. I’VE BEEN WAITING UNTIL WE GET A LITTLE CLOSER TO THE ELECTION TO WEIGH IN ON THIS ONE. But with said event exactly two weeks away (gulp...or maybe it's yay?) I thought I'd take a minute to drop a few thoughts.

Even the most ardent Nate Silver groupie has to admit political polling has taken a beating. It was way off in 2016, way off in 2020, and could well be way off again when Americans finish going to the polls to elect a president on November 5. (It was more accurate in 2022, but only without Donald Trump's x-factoriness on the ballot.) All of which makes polling's obsessive predictions kinda useless.

By now the reasons for these challenges are well-documented. Pollsters are legally limited to landlines, and landlines skew much older than the electorate. Pollsters are culturally limited to people who have the time to answer polls, and those people skew in a different direction than the working/studying/family-raising lion’s share of the electorate. Pollsters rely on humans to give answers, and humans don't always like telling the truth.

The idea that machines can solve this problem seems, like the idea that it could solve a lot of problems, rooted slightly in reality but mostly in fantasy. People are free-thinking, unreliable, human. And AI, no matter how much training data you give it, cannot be taught how to be any of this. That's why using AI to write a novel or serve as your emotional companion has been such a challenge — no matter how good the processors, it can't capture these ineffable qualities of your favorite writer or best friend.

But polling represents a more distinct set of circumstances that may in fact be friendly to an AI solution. Because here lies a realm in which you actually want to wipe away some of this strangeness. The free-thinking weirdo that lives within us in fact works against the science of polling. If a human doesn't tell a pollster the truth about who they're voting for because they're being, well, an unreliable weirdo, then that vote will be miscounted.

But an AI, without that unreliable-weirdo quality, might tell you exactly what it plans to do.

Well that's great, you say. But AIs aren't voting.

Ah, but what if they were? Or rather, what if they could take the place of the humans being asked in the polls, and then we used THOSE results to project the election?

That's the premise of a new company called Aaru, run by some very young data-minded upstarts. As reported by my former WaPo colleague Reed Albergotti (now at Semafor), these founders came up with some truly detailed portraits of voters with the help of AI.

Run by Cam Fink and Ned Koh, a couple of NYC college dropouts who are not yet 20, Aaru built its pool of AI voters with many traits drawn from census and other data (jobs, marital status, ethnicity, gender, economic status, along with a slew of squishy factors like "aspirations”). It even fed them a diet of their favorite (if hardly healthy) news sites.

Then, when these voters were fully formed — engorged and drunk-happy on the larded offerings of our political-news menu — the system asked these AI "people" who they would vote for. More than five thousand of them, in (presumably) many swing districts. (The five thousand is notable — one nice part of this AI modeling is since it’s so much cheaper and faster than the call-up-real-people style of polling you can use a much larger sample size.) All of this is described by the unsexy slogan of "Rethinking the science of prediction through multi-agent systems." But it’s actually pretty sexy.

So what happens when this system was unloosed into the world? These AI mock-voters were so accurate that the company was able to predict the Latimer-Bowman Congressional primary in Westchester County not far from my NYC neck of the woods last June — an election in which some 77,000 people voted — within 371 votes. (!)

Of course, one accurate polling turn does not a soothsayer make, and I have a lot of very basic data questions that were not answered by the pair's explanations. Can Aaru garner as much information about these highly disparate places from Georgia to Michigan to Arizona as they did in one largely suburban New York county where the confounding variables are much fewer?

How do they account for turnout challenges — that is, how much do these AI minifigs incorporate the possibility that some people simply won’t vote (a problem also faced by traditional polling)?

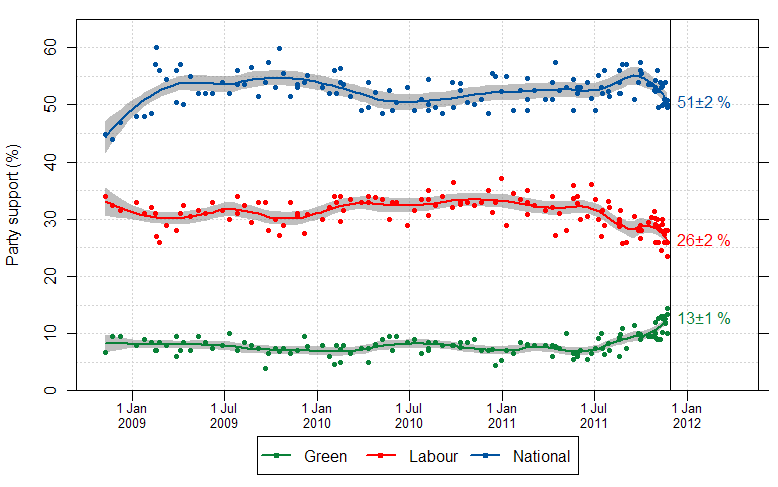

And again, this election features Trump, who confounds the pollsters. (Fink and Koh do say that they retrospectively outperformed all the major polls in 2016. Their model predicted 51.4% Clinton to 48.7% Trump in the popular vote — much closer to the 51.1%-48.9% final tally than CBS News, ABC News or Fox News, which all had Clinton over 52% and Trump below 48%. So Aaru can at least claim they accounted for the Trump underestimation, which comes from supporters lying to pollsters about voting for him, with their non-lying AI.)

I'm also skeptical of some of Aaru's bigger boasts, like the fact that real-time data can be fed into the model to replicate a person who might've just logged onto Instagram right before the pollster called. “We can watch, theoretically, the impact of every tweet that gets posted," Fink told Semafor. But training takes longer than that, and is also not as simple as that.

So what is Aaru predicting for 2024? It says that Kamala Harris will outpace Trump by 4.2% in the popular vote. But we know how meaningless the popular vote really is. If Aaru had spit out forecasts for swing states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, Nevada, North Carolina and Wisconsin — all places where the polls nailbitingly have the contest within one percentage point — it wasn't saying.

Polling's problems are legion. AI may be no better — or may have different problems. But this is a case where AI is correcting a system that isn't working too well in the first place, and so probably worth a listen. Because it's possible that humans are messy and complicated, and our polling preferences tougher to forecast than we know.

But it's also possible that they're actually much simpler than we tell ourselves, and AI has just managed to find a way to peek through our thickly self-imagined cloak. Albergotti is slightly simplifying but not grossly distorting when he says that LLMs "were trained on nearly every word that anyone has ever put on the internet. Completing the sentence ‘I will vote for X’ when lots of other contextual data is included should not yield a very high margin of error." (This does presuppose that humans are programmed primarily by everything they read on the Internet — I'll let you draw your own conclusions on that one.)

One last thought. All the talk about polling centers on trying to figure out voters. But 155 million Americans voted in 2020, and attempting to know what they all might do — or slicing off highly divergent slices of them and aiming to come to a meaningful conclusion — may be going about the question wrong. Perhaps the data hose should be focused not on the bottom but the top — on the candidate qualities that predict election.

I am referring to Allan Lichtman's famous “13 Keys Test,” his list of sometimes slippery questions about everything from candidate charisma to economic recession in which the incumbent party will hold power if it meets eight of the keys.

Lichtman's system has famously forecast each of the last ten presidential elections correctly, and while some think this is little more than a demonstration of broken-clock syndrome, other respected thinkers swear by it.

This year, you may know, he said that Harris easily meets at least 8 and possibly as much as 10 of the keys, putting her in the White House. That’s not a conclusion reached with advanced mathematical formulae, let alone sophisticated computer coding. But it’s also not based on polling. And that just might be enough.

2. DRONES HAVE BEEN USED FOR DECADES TO BOMB MILITARY TARGETS, with numerous ethical variables. They put fewer pilots in harm's way but also (as a result) make the barrier to unleashing deadly missions that much lower; you're a lot more likely to initiate attacks if it costs you nothing but a few bucks in equipment when the attack goes wrong.

The wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have seen an uptick in drone usage. In Ukraine they've been used as a way to leverage a significant equipment disparity between the Ukrainian and Russian armies.

And in the Middle East, Hezbollah has deployed drones repeatedly because, as unmanned slow-moving craft, they can more easily slip behind air defenses that are designed to detect rockets and missiles. Just last week, Hezbollah was able to sneak a drone into Israeli airspace and kill four Israeli soldiers on an army base. A few days later it crashed a drone near the coastal house of Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

So drones, while not new, are becoming a bigger part of modern warfare. With all the moral calculations that come with it. And lowering amounts of human control. (As our go-to AI-weapon expert Tony Pfaff has noted, drones are much more easy to operate autonomously than any kind of ground weapon.)

But I wanted to spend a quick second on so-called “drone swarms." Because they're both impressive and ethically scary as hell.

Right now drones are meant as one-off attack machines, operated either by a human, operated autonomously, or operated autonomously until a human is called in to make a big decision (known as in the loop, out of the loop or on the loop, respectively).

But there's a limit to what one or even a few drones thus operating can do — they can basically pick out a target, fire at it, then move on to the next. This is Edison's bulb compared to the stadium floodlights that military commanders really want.

No, the next phase of this battle is "drone swarms." Essentially it's a whole group of drones that can fly autonomously and communicate, collaborate and even make collective decisions about their mission. Like a fleet of aircraft in which the pilots all talk to each other, only with AI. If one misses a target, another can pick it up; if a few come under fire, the others can peel off and attack the threat.

In one simple test, one drone hovers while the others must fly close to it and decide who goes first/how they avoid crashing into each other, learning literally in real time how to pull that off.

Think Top Gun sans the Maverick and Rooster banter. Just the creepy disembodied reality of these drones working together toward a shared killing goal. (Not all of the uses are military, of course — you can use drone swarms to create a cool spectacle too. But let’s be real, the money and the heat comes from what they can do to attack.)

This video breaks it down well.

Drone swarms are becoming more probable in battle as AI gets better at both adapting to changing conditions and recognizing what other AIs are doing. It's actually not easy for a machine intelligence to react to another machine intelligence — that requires a more human brand of reasoning — let alone to coordinate with one another. But these efforts are bearing fruit.

The U.S. military has been pouring millions into drone swarms, with contractors and university researchers even developing a “language” (called “Drodish”) that will allow the drones to communicate (basically, coding that they can invent on the spot to message with other drones when they come upon an unfamiliar situation). Military officials have even studied a species of beetle that works collectively to help in the effort.

China, already a drone giant with its DJI behemoth, has been way ahead of the game with drone swarms. A few weeks ago came reports that drone swarms could even be used in a potential attack on Taiwan.

Israel supposedly deployed the first-ever drone swarm in battle back in 2021, using it primarily to expose enemy hideouts in Gaza. (Hezbollah called its recent attacks a drone swarm but it’s unclear if they meant it in the way we do or just as a lot of drones operating independently.)

Oh, and of course Russia’s on the case, too.

This week a paper from the Indian think tank Observer Research Foundation noted that drone swarms were basically the submarine or nuclear weapon of our time — something countries were racing to develop under the belief they could change the nature of battle. “Single drones are increasingly being integrated into collaborative drone swarms,” the organization said, noting that “Armenia, China, France, India, Israel, the Netherlands, Russia, Spain, South Africa, South Korea, and the US all have drone swarm programs under development.”

The Pentagon is, at this very moment, stumped by a drone swarm that flew over sensitive sites in the D.C. area for more than two weeks last December.

What will this all mean socially is not trivial. One of the main characteristics of autonomous weapons thus far is that they essentially function as lone wolves; to build an army or any kind of collective fighting force you still need people. This shifts the model — recalibrates our brain to think about war not as groups of people in a command structure engaging in battle but a flat hierarchy of machines working together without any of that. Not for nothing did the anti-AI weapon group Stop Killer Robots warn that if the drone swarm “continues unconstrained, humans will eventually be cut out of crucial decision-making.”

What this will mean morally is consequential too. Utopianists have argued that all these autonomous forces could lead us to the world of the classic “Star Trek” episode “A Taste of Armageddon” in which wars are fought entirely by computer simulation. But most military experts don’t believe that. Quantum leaps in fighting efficiency like a drone swarm, they say, are more likely to make wars fought in the first place. And the weapons won’t be fighting other autonomous forces but used on people — that’s what exacts a toll and applies the pressure, after all,

The idea of a drone swarm fighting another drone swarm might seem like an appealingly human-free way to fight wars.

More likely, though, the drone swarms will be used to more ruthlessly attack human targets. Which could then unleash another drone swarm attacking humans in return. When it comes to war, efficiency doesn’t necessarily bring good news. It just means more killing.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. Last year ended with a score of -21.5 — gulp. Can 2024 do better? The year started off strong but the summer wasn’t great. This week is more…mixed.

AI POLLING MIGHT ACTUALLY BE USEFUL: +3.0

BATTEN THE HATCHES FOR THE DRONE SWARM: -4.0