Mind and Iron: A better way to choose politicians?

Inside the wild and and wonky world of ranked-choice voting. Also, what color is your parachute and will AI be forcing you to eject?

Hi and welcome back to another spicy edition of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and lead cannery worker at this Heinzy news factory.

Every Thursday we offer coverage of AI, tech, innovation and the future — no additives, preservatives, or mainstream-journalism equivocating politesse. Also, we try to avoid phrases like equivocating politesse. We're always independent, beholden to no one. Consider supporting the mission.

This week we're going to take you inside a mathematical innovation known as ranked-choice voting. RCV, as the wonks call it, is the method of tallying votes that just may yield more representative outcomes — and prevent fringe candidates with hardcore followings from gaining a foothold. It could well be our future at the ballot box.

Even more timely than that election-y material (or, sort of running in tandem with it) is the issue of job displacement. How much will AI eliminate jobs and throw people out on the street, particularly white-collar workers?

It's an unanswerable question, unless Sam Altman is the one giving the answer, in which case AI will not take away jobs so much as make it so that no one will ever have to work again as they chillax counting their crypto millions at a beautiful White Lotus resort. Back in the real world, though, the answer is unknowable.

But researchers writing in Harvard Business Review are attempting to know it. A big study came out from them this week on just how many jobs might be lost — even how many jobs might already have been lost. We'll give you the deep skinny on whether your profession is on the list in the item below (at least until we can figure out how to get an AI to write it for us).

Also, we’ve got a cool poll about something that could be insinuating itself into a lot more of our lives. A question to drive you to distraction.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

“It allows people to be inclusive — ‘I can put together a team to represent me.’”

— Suffolk University political scientist Rachael Cobb, on the novel way of voting known as ranked-choice

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

A pleasant ride to nowhere?; voting with the whole sheet; AI and your job

1. FIRST THIS WEEK, I’M IN LOS ANGELES AT THE MOMENT, AND WAS THRILLED/HORRIFIED to look out the window of my Uber going down Olympic the other day and see a Waymo gliding by, its driver seat (and indeed all seats) eerily empty. “Hello, machine-overlord driver,” I said to it as we stopped at a light. And though no one answered, I knew they were in there, hiding behind their invisibility cloak.

Anyway, the car seemed to be on its way to pick someone up (Waymo became available to the general public in L.A. just this week) which gave rise to this question in my head. And so I thought I’d ask it of you too:

Hit the vote button and let me know what you think; I’m curious about the attitudes on this (and whether I should order a Waymo the next time my Uber is taking too long).

Now speaking of voting…

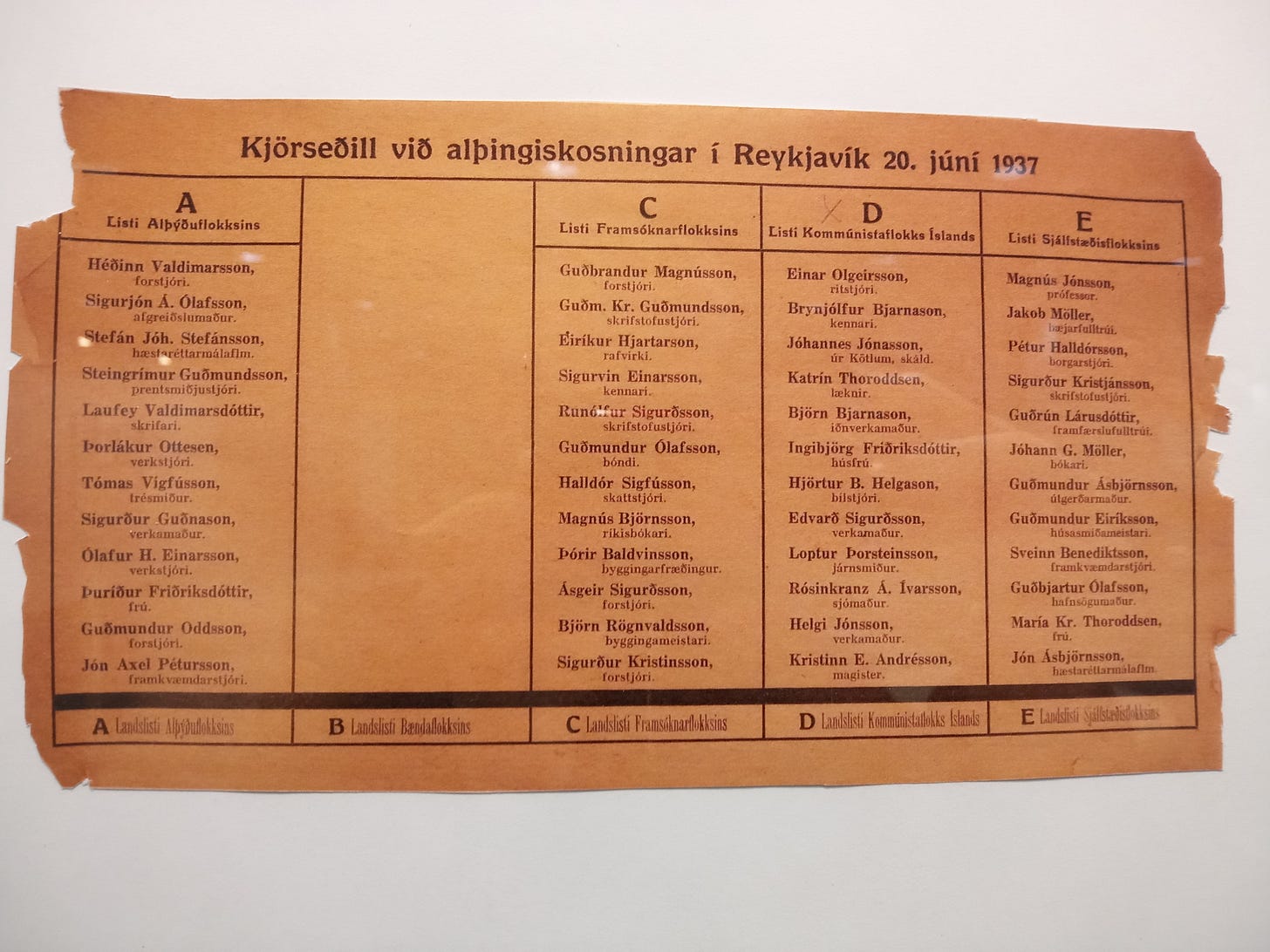

2. DID YOU EVER HEAD OUT TO VOTE IN THIS DEMOCRACY OF OURS AND THINK, ‘THERE’S GOTTA BE A BETTER WAY TO DO THIS?’

Particularly in situations where there are five or six candidates (like a primary) or five or six parties (like a parliamentary election) — where a whole scrum of possibilities stares back at you and you just can't decide which ones stands out from the rest?

Well, there is a better way.

Ranked-choice voting is not new. In fact, you probably did it a version of it a half dozen times before you were 10, getting together with your friends and ranking your favorite ___, then adding up all the scores to see which one came out on top.

In adultland, it's been employed in some elections for a while now. San Francisco began trotting it out for municipal elections since all the way back in 2002. Most pop-culturally it's been used at the Oscars for best picture beginning in 2010. In more recent years it’s been a feature of political races from Maine to Alaska, in the 2021 New York Democratic mayoral primary and plenty of others.

Under the most popular form of RCV (known an instant-runoff voting) voters enter the polling booth choosing from a list of candidates — let's say Whitmer, Booker, Shapiro, Buttigieg and Klobuchar, to take five totally random names. They rank them according to preference — literally 1-5 of who they'd most and least want to see win.

Counters then make piles of the ballots based on everyone's first choice. If one of the candidates has more than 50% of the total vote, they win outright on the first ballot. (This almost never happens.) If they don't, the shortest pile — i.e., the candidate that received the fewest first-place votes — gets swept off the table and redistributed to all the other piles according to their second-place vote. Their vote is not wasted, in other words; their next choice is counted.

Then the piles are tallied again. If one candidate now has 50%, they win the election. If not, we go to the shortest pile remaining once again and count their second choice (or third, if second is also off the table ) and redistribute again. Until someone eventually gets 50%.

The advantages to this are clear. First, a voter feels like they are able to convey a fuller picture of their preferences since they can weigh in all the candidates, not just the one they want most. Second, a vote for a less popular candidate is not a vote wasted, because there's a good chance that the voter’s second-place vote will be reached. This, incidentally, could have the effect of making people more inclined to pick a niche candidate in the first place, potentially diversifying the results.

And the most important and relevant benefit — and this isn't fully proven, but plenty of researchers think it likely — it leads to less divisive candidates winning office.

Because the way to win an RCV election is, generally speaking, not with relatively few first-place votes but a lot of second- and third-place votes, the system naturally selects the candidate with broad appeal/acceptability vs the more hardcore polarizing choice.

One proof of this is at the Oscars. In 2010 the Motion Picture Academy expanded the best picture nominees from five to as many as 10, and they needed a way to ensure that a movie with 11% of the vote didn't win best picture while a whole bunch of contenders fell short with just under 10%. Enter RCV. The ol' rank-monster.

Soon enough, a lot of smaller likable movies — pictures like "Moonlight," "Spotlight" and "Parasite” — were winning over bigger more bombastic films that might have won in the past. "Spotlight" is a particularly telling example. In that 2016 year the seeming favorite was "The Revenant," which had the bigger production values, studio backing and flashy performance from Leonardo DiCaprio. But the movie was also divisive, with some loving it and some hating it thanks to a number of brutal scenes and an aura they found self-indulgent. The Boston Globe investigation-themed "Spotlight," with its smaller performances and humble mission, was at least liked by pretty much everybody, even the many people for whom it was not their first choice.

In a straight up and down election, "The Revenant" probably would have won. There would be, say, 30% of the academy that would have chosen it, leaving the other seven movies to split the other 70%. Even if that entire 70% really didn't want to see "The Revenant" win, there was nothing they could do about it; all their votes would be diffused across seven movies.

But with ranked-choice voting, the whole picture shifts. Those 30% of voters still put "The Revenant" first. But many in that group put "Spotlight" second. Meanwhile the other 70% had some people putting "Spotlight" first, and then a whole bunch of others with different top choices putting “Spotlight” second or at least third. When the shorter piles started getting tossed, those votes all went to “Spotlight.” And that’s probably how it won best picture.

Put simply: an RCV system preferences the broadly liked over the niche loved. Which, when you're talking about a representative democracy, seems like the far better outcome. (It also could lead to less polarization — the candidates we're consistently putting in office will be liked by people across the spectrum instead of loved by just a small group of hardcores.)

So that's the theory. Political scientists have been studying it for a while to see how it works in practice. Not everyone thinks it does, I should note. Some of the most intensive studies have come from a political scientist named Lee Drutman at the New America think tank. He’s essentially concluded that the benefits on polarization are there, but modest. In general, though, there appear to be plenty of advantages.

I asked Rachael Cobb, an assistant political science professor at Massachusetts’ Suffolk University who’s studied RCV, what she thought. “It allows people to be inclusive — ‘I can put together a team to represent me,’” she says.

But it’s more than just a feeling, she adds. The research as she’s seen it does suggest more middle-of-the-road liked candidates get elected as opposed to divisive ideologue types. As a result, “the demand for purity goes down [because you don’t need to satisfy the high bar of a small group of people] which has been a real problem in our politics.” That lack of purity testing means, she says, “there’s less a cult of personality. It’s more about issues that they’ll bring to the table.”

I don’t want to minimize the downsides; there are several. Those who want to make a statement by voting for a marginal candidate will not be able to do so, for instance, because they end up getting counted on a different pile once their short stack is swept away. But as a rule RCV reflects the will of the voters a lot more; it’s a pretty nice curative. Even in a general presidential election with fewer candidates the system could offer some benefits by removing the third-party spoiler. Under RCV an election with Ralph Nader or Jill Stein or Ross Perot no longer siphons off votes from the one of the two major-party candidates — their supporters can choose them but still have a major-party second choice that would end up getting counted.

All of which makes it surprising and disappointing that voters last week in Colorado, Oregon, Idaho and Nevada all failed to pass a proposition to accept RCV, and Missouri actually went and banned it. (Ah, Missouri.) D.C. passed an RCV proposition.

And Alaska, which had used it since 2020 for all state elections, is seeing a repeal effort come down to the wire as the vote as of today is too close to call.

I think RCV will eventually take hold in more and more places as people understand how much more representative it actually is and as a hunger (hopefully) to tone down the divisiveness grows. The Colorado and Nevada votes, for instance, were super-close, and I imagine the RCV crowd gaining support as awareness increases.

In fact, in some ways it’s hard to imagine an RCV proposition ever losing since almost by definition RCV benefits the majority, not the hardcore outlier, so you’d think the majority would vote for it.

Leading you to one of two conclusions about these votes last week: Everyone thinks they’re a hardcore outlier, even if by definition they can’t be. Or they had no idea what they hell they were looking at. There are, unfortunately, few curatives for ignorance.

2. ‘HOW VULNERABLE IS MY JOB TO AI’ IS THE QUESTION anyone who’s machine-conscious has been putting at the top of their list for the past couple years (right ahead of the other question heading the page, 'And what do I do about it'?).

The answer can seem slippery — it depends on unknown factors like the evolution of particular technologies and the adoption of particular industries, along with more known factors we tend to misunderstand, like how unique our skill sets really are (Ninety percent of drivers think they're better than average, etc).

With that murkiness, we'd welcome some clarity on where we stand, at least broadly. (An app that customized vulnerabilities to us and then offered ways to shore them up would be a killer idea. VC's if you're listening.)

That wish was granted this week with an article in the Harvard Business Review from researchers mainly at Imperial College London Business School. The article possessed the rather generic title "How Gen AI Is Already Impacting the Labor Market" but the rather explosive goal of breaking down which jobs are already most vulnerable to AI.

The trio of researchers, who are publishing their technical findings in the journal Management Science, took more than a million ads from a freelance-jobs board and examined them before and after the release of ChatGPT (two years ago this month). They broke down those jobs into three categories: “manual-intensive jobs (e.g., data and office management, video services, and audio services), automation-prone jobs (e.g., writing; software, app, and web development; engineering), and image-generating jobs (e.g., graphic design and 3D modeling).”

In certain categories, the falloff was conspicuous. As they had it:

“Writing jobs were affected the most (30.37% decrease), followed by software, app, and web development (20.62%) and engineering (10.42%).”

They did the same for image-generation tools like Midourney, Stable Diffusion and Dall-E, many of which came out in the summer of 2022. Their finding:

“A similar magnitude of decline in demand was observed…Within a year of introducing image-generating AI tools, demand for graphic design and 3D modeling freelancers decreased by 17.01%.”

Their conclusion is rather dramatically stated: “The short-term impact of gen AI on specific roles — especially those susceptible to automation — has been swift and unavoidable. Compared to traditional automation technologies, the speed and extent of gen AI’s effect are unprecedented.”

Now let’s leave out the correlation-vs.-causation problem here. A lot of other stuff was happening during the timeframe of this study. The year 2023, for instance, is when many media outlets began feeling an economic pinch and cutting back their budgets, which might well have accounted for a decline in writing or design jobs. (Plus it’s possible as part of those cuts employers just asked people in-house to do the work instead of freelancing them out, which still doesn’t mean humans were being replaced.)

But even if you discount those factors, there remains an issue in measuring things this way. Because this data doesn’t mean that AI took freelance jobs — it just means that companies thought that AI might be able to do freelance jobs. That is, AI didn’t get anywhere near good enough to become an ad-agency graphic designer or a newspaper reporter. But a bean-counter thought they might, so they cut back on their budgets in the hope that was the case. (Presumably this would come back over time, but the study doesn’t stick around to find out, stopping relatively quickly at July 2023.)

All we really can say here is that some employers slowed down their freelance hiring shortly after the tools were launched. And I’d argue the tools were not nearly good or widespread enough by July 2023 — they’re hardly good or widespread enough now — to start pushing out people en masse.

Also, none of this says anything about newer modalities like video or audio, or straight-up decision-making programs that might affect investment firms or medical practices. It’s cute that AI-related displacement is seen as just a matter of text and code, like we’re stuck in some mid-2023 world Silicon Valley has clearly moved past.

Just the same, I think there’s a meaningful data inference here, and it concerns more of the relative truth: That the perception is of writers and illustrators being 50% more machine-replaceable than software developers (30.37% to 20.62%), who are themselves twice as replaceable as engineers (20.62% to 10.42%).

One last point that occurs to me as we’re delving into the results. This study measures only freelance work, not full-time. It’s entirely possible — in fact from this study actually persuasive — that companies may be keeping all their full-time employees or even adding to them but cutting back freelance due to AI. That is, AI isn’t replacing jobs; it’s simply putting the focus on full-time employees because AI makes them more efficient, reducing the need for stray freelance projects.

You don’t need to convince me of the very real concern over AI-related job displacement. But from this study, at least, I’d argue there’s plenty of reason to breathe easier. Even as someone in the dreaded writing category.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. Last year ended with a score of -21.5 — gulp. Can 2024 do better? The year started off strong but the summer and early fall haven’t been great. But the clouds part this week.

ROBOT CARS ARE HERE TO SERVE: +2.0

A MORE REPRESENTATIVE AND LESS POLARIZING FORM OF VOTING ESTABLISHES ITSELF: +4.0

A DARK STUDY ABOUT AI JOB DISPLACEMENT ACTUALLY ISN’T VERY PERSUASIVE: +1.5