Mind and Iron: The five surprisingly important tech stories of 2023

Under the radar, they'll still change everything.

Hi and welcome back to a special holiday edition of Mind and Iron. I'm Steve Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times and Will Ferrell to this merry band of elves.

This is the 25th issue of Mind and Iron, where do the days go. That’s 25 issues of examining how our intuitive human minds might mesh with, be enhanced by and come under threat from analytical machines — 25 issues of examining how we might ensure humans are at the center of this new AI age.

Please sign up here if you’ve gotten this as a forward.

And please consider a holiday pledge of a few dollars here. It will get you all the Mind and Iron features as we move to a paid model in the new year and ensure we can keep going with our mission.

Since we're wrapping up matters for the year (no ditty next week) this issue will do things a little differently — we’ll take a look at the important stories of the past year. For all of us who care about where humanity is headed, it’s been a bonkers 12 months, filled with beautiful portents and frightening omens, great discoveries and terrifying developments.

Now you don't need me to tell you, in December 2023 of the Year of Our Lord Roy Kent, about the boardroom drama at OpenAI, or the popularity of ChatGPT, or anything else that drenched our homepages over the past 12 months. Instead, here’s a more helpful offering: We’ve cherrypicked five stories from the past year that you may have only casually heard about (if you heard about them all) and underline why they're so important. Across science and business, these slept-on events were unexpected, or noteworthy, or both. And they could change the trajectory of the future in profound ways.

Speaking of looking back, since it ran in ye olde issue #1 and some of you had yet to hop aboard, we’re resurfacing a story from that time. It's about a tech-enhanced vision of financial freedom ending tragically, and I think it illustrates perfectly the theme of this newsletter: how Silicon Valley promises of a shinier tomorrow could turn dark quickly if we don’t keep an eye on the switch.

And finally, just above that, our Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score is currently at -30 for the year. Which…isn’t good. It means we’re MUCH further from a happy future than we were when 2023 began. We’ll see what these milestones can do about it.

First, the future-world quote of the year (!). It comes from that story in Issue No. 1. And while it was said about a very particular tragedy, I think it’s a handy metaphor for what society would face without a counterweight to so many tech profiteers.

“For them it’s just a game. And for him, he was giving part of himself.”

—Sarah Whibley, friend of an everyday man who lost everything because he believed in a tech that hadn’t been guard-railed

Thank you so much for being a part of this growing community over the past six months. I feel beyond lucky and grateful, and can’t wait to see what the new year brings.

Now let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week year

Here’s your 2023 rundown

1. An AI deepfake temporarily shakes the stock market

Amid all the frenzied chatter of what AI could do, this moment last May passed by almost unnoticed, swallowed up by a fresh news cycle practically the next day. Yet it marked a crucial turning point.

A photo showed thick black smoke curling skyward near the Pentagon, with the accompanying post claimed an ominous explosion. Soon the image had caught on across social media, was picked up by investment platforms and did what news events do: caused the S&P 500 to sink. Investors reasonably worried what a terrorist attack on U.S. soil would mean to markets and began selling.

Ah, but there was a catch: the image was AI generated.

The markets quickly corrected and everyone breathed easier once they realized this was just the work of a troll with some programming know-how. (To their credit, Facebook and other platforms posted explainers and deleted/blocked access.) But the significance was starkly revealed: Manipulated AI media can change markets. And if it can do that, it can also impact elections, wars, social cohesion and so much else.

The technology used to create the image wasn’t even that sophisticated (a number of details gave it away as AI). That’s what was so notable. Because if something like this could have an effect…

The moment crystallized a major truth: that convincing AI photos (and videos) are coming. And could leave a lot more than temporary market crashes in their wake.

2. India lands on the moon

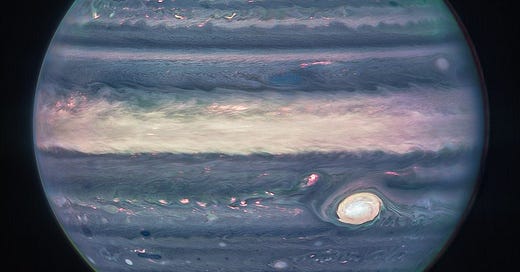

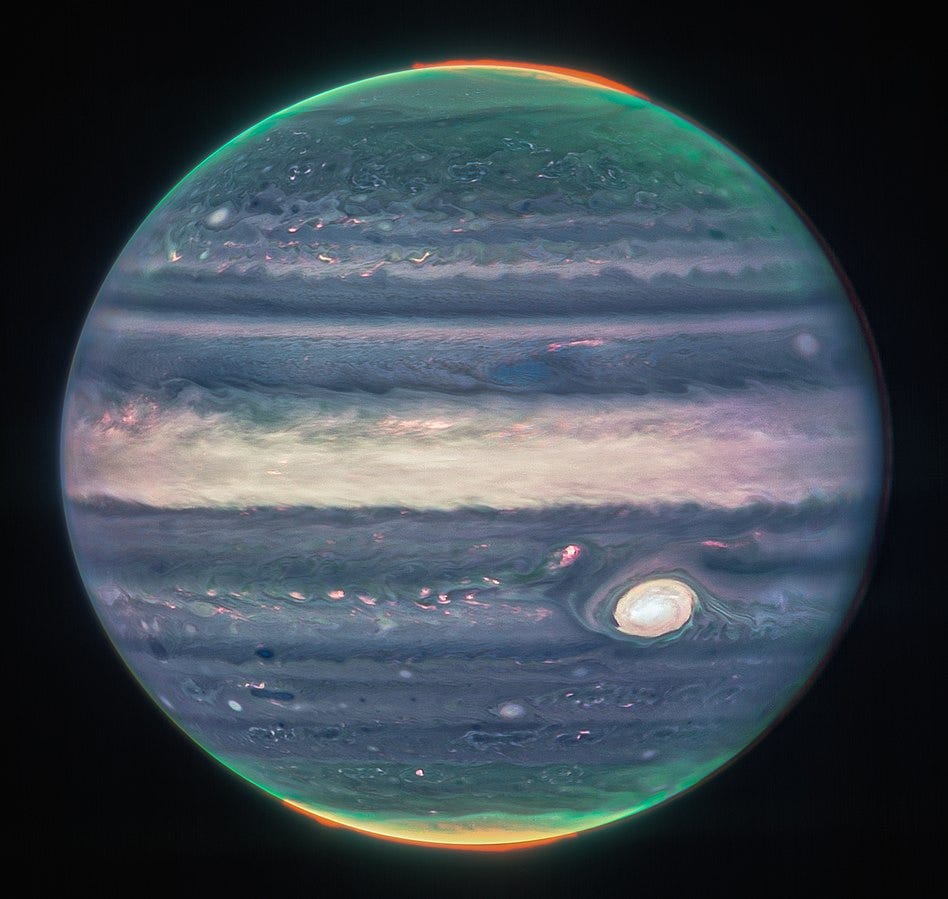

Between the magnificent images sent back by the James Webb telescope and the sundry list of SpaceX fails, it was easy to overlook what India pulled off this year.

As part of the country’s Chandrayaan-3 mission, the lander Vikram and rover Pragyan touched down on the south pole of the moon in August. They then set out to survey the surface and run experiments to understand its composition.

The Asian nation had become only the fourth country in history to achieve a moon landing, and the first to land on the moon’s south pole. But even more important, India did all this for a shockingly low $75 million. Chandrayaan-3 was an efficient mission — in dollars, fuel and so much else.

What became clear with their success is nothing less than a new future of space-exploration — one that’s spread around to countries (and companies) well beyond the superpowers that have dominated for nearly 70 years, and, even more important, to programs that don’t require superpower budgets. India now aims to put a man on the moon by 2040 with the same efficient approach.

That the country beat out Russia, which had a failed moon-landing a week earlier, underscores the point. ("The apparatus moved into an unpredictable orbit and ceased to exist," Russian state space company Roscosmos said of the failure, with enough metaphoric overtones to make that the future-world quote of the year.)

Of course questions remain over which public or private entities will dominate space travel in the coming years. But with the India landing, it became clear that this mad race will contain some unexpected entrants. With no way to know who will win — or where they will take us.

3. The FDA allows lab-grown meats

Every quarter-pound burger consumed in this country requires 15 gallons of water, 65 square feet of land and four pounds of green-house gas emissions. Considering Americans eat 50 billions burgers each year, this is a…problem for the environment.

That's one reason why the ability of lab-grown meat companies, as of 2023, to sell their products commercially is such a big deal. In June the FDA gave the greenlight to two firms, Upside and Good Meat, that produce the lab-grown stuff, which is meat and chicken cultivated from animal cells — no farmland, emissions or actual animals required.

The meat is still specialized enough that it costs an arm and a leg (not lab-grown) to buy. So it's a novelty for now. But skeptics said that about every food-tech advancement over the last 50 years, and when was the last time anyone who's eaten a TV dinner, protein bar, genetically modified vegetable or Impossible Burger thought about them?

Expect lab-grown meat to scale up big time in the next few years, pitting the powerful ranch lobby against the climate- and planet-conscious. Don't be surprised if the next environmentalist battle takes place exactly on this field — or if the fundamental nature of eating and agribusiness is permanently changed. This FDA decision opened the door.

4. Sarah Silverman sues AI companies

Alarmed by the sight of their work in the AI blender with not a word of request or dollar of compensation, Silverman and other authors in July sued both OpenAI and Meta for copyright infringement. The plaintiffs filed a range of claims that boil down to the technical legal argument of: who the heck said you could do this?

“[We] did not consent to the use of their copyrighted books as training material,” the claim said. In the upcoming Revolutionary War over AI and copyright, this was Lexington and Concord.

The judge in the case has since dismissed a large chunk of the complaint, though a core claim — that the training infringed on the authors' copyright — is still moving forward.

But the specific outcome here may be less important than the precedent. AI relies on material that is deeply proprietary, and Silverman & Company's willingness to take a stand (which mirrors a similar legal move by artists against Open AI's Dall-E and other image-generators) is only the beginning.

Tech companies need creative entities (as much as they like to pretend they don't), which means this is only the first of what will be many salvos in their power struggle. At stake is nothing less than what AI can do and who gets to control and profit from it.

5. Researchers find that gene editing can cure sickle cell disease

We’ve been told so long about the promise of cutting-edge technology to cure disease that the hype almost seems like its own epidemic. Yet in August we got a rare gift: hard evidence of how this is possible.

A dozen researchers, writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, told of a trial of the “Exa-cel” technique, which uses CRISPR to basically edit the disease out of the DNA of 30 patients with sickle cell anemia. No fewer than 29 of them saw themselves partly or essentially cured.

For the 20 million sufferers worldwide of sickle cell disease this was a godsend. For the rest of us? It’s a portal to a world in which gene editing can solve our most incurable diseases.

Now, the Exa-cel treatment is intensive and painful; the risks are many and unknown; and the costs are astronomical. This is not the last rung to the roof — it’s barely the removal of the ladder from the garage. And yet. The trial was a massive breakthrough, hinting at an entirely new approach to disease-treatment in the 21st-century. When the FDA approved the treatment two weeks ago after several months of investigation, it brought the story to a happy first-chapter conclusion. We now live in a world where gene editing is a plausible weapon to fight disease.

We have no way of knowing where this is all going. But 2023 brought what society has dreamed about for centuries: a new way to stop what kills us.

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way.

For the year the score was -30 — oof. But what happens if we factor in the above milestones? (Besides Silverman, who was factored in this summer.)

AI DEEPFAKES RATTLE MARKETS: -5

LAB-GROWN MEAT MOVES CLOSER TO MASS-MARKET REALITY: +4

THE SPACE RACE MOVES AWAY FROM THE JUGGERNAUT WEALTHY: +3.5

GENE EDITING CAN CURE DISEASE: +6

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score for these events:

+8.5 (hey not bad)

The final Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score for 2023:

-21.5 (let’s hope for better in ‘24)

BigMind

A longread on something kinda serious and/or important

OK, here’s that story.

Crypto’s Tragic Figure

The email stares at me, daring me to open it.

“We had a victim in our group commit suicide back in May,” the subject line reads.

My stomach sinks. I switch tabs. I don’t want it to sink any further.

The “group” is a Facebook group, and it includes hundreds of victims of a romance-based cryptocurrency scam known as pig-butchering that had claimed at least $66 million in people’s crypto with the help of a woman who called herself Alice. It is the summer of 2022, and a few months earlier my colleague Jeremy Merrill and I had broken the scam story, focusing on a victimized former Atlantic City cop named PJ. PJ’s story was like so many others', in which a single man between the ages of 30 and 60 is cajoled by a woman he meets online (herself likely conscripted by a crime ring) into slowly giving over his trust, and eventually his money, on Coinbase, from where it is stolen.

The email on this afternoon has come from another of Alice’s victims, a 48-year-old Ohio actor named Troy. His subject line suggests the worst possible outcome.

I gulp and click ‘open.’ The message and a quick Google search of local news coverage reveal what happened.

On May 25, 2022, in the very early hours of the morning in the western English town of Chippenham, a 51-year-old man named James Hutcheson — Hutch, to his friends — stepped onto the tracks at a station near his home. He was killed instantly. Authorities had ruled it a suicide. Hutch had been a British Transport police officer for nearly 28 years.

What the coverage didn't say (but the Facebook group did): Several months earlier Hutch had lost $115,000 to Alice.

It’s of course impossible to know exactly what Hutch was feeling. But conversations with other Alice victims had returned an almost identical set of emotions. Resentment toward the scammer. Anger at Coinbase. Frustration with law enforcement (little of the victims’ money has been recovered).

And, ultimately, the inexpressible regret that comes from knowing you’ve thrown away, with one lapse, so much of what you’ve worked for.

I, on the other hand, feel nothing but anger. All the people in a position to do something about this instead just succumbed to inaction — the law-enforcement officers, the Coinbase executives, everyone else who Hutch and so many other victims reached out to. They all just whistled through their day, too unbothered to follow up. And now a man was dead.

Then it hits me. I am one of these people.

HUTCH OBSCURED

The email looks right back at me, and I am scared to open it.

Hi Steven

I lost 115k usdt to the same scam as PJ.

I’m in the UK but the story sounds the same.

I can be called on XXXX.

James

The message had come on April 5 2022, a day after our Alice story was published. In the flurry of emails from other victims after the story ran — and using the journalist’s clinical calculus in which new scams go to the top and more-of-the-sames get backburnered — I never replied. As I look at it now I notice I had even forwarded the note to my personal account, the usual trick of putting it on my digital to-do list. But that somehow makes it worse: I'd wanted to do something but didn't.

Sure I could rationalize it — mental health is complicated, my response may have not done much to give him hope, hadn’t I already done my part by writing about the scam in the first place?

But there’s no way to really know how accurate that thought is. Maybe my consolation or continued investigation would have done nothing to change Hutch’s fate. Or maybe it would have given him just a little bit more hope to carry on. Maybe I could have written something to him that day — to this man seeking hope wherever he could find it — that wouldn’t have led to him taking his own life six weeks later.

Because the reality is that when it comes to scams — particularly scams in the murky world of crypto — complicity is everywhere. When confronted with the constant barrage of money lost, many of us say caveat emptor and move on with our day. But opportunities abound to help. I had a juicy one. And didn’t jump at it.

I begin reaching out to people who were close to him. A part of me obviously wants to assuage my own guilt — wants to learn something, anything, that alleviates my responsibility. But I also want to honor Hutch, if entirely too late. Who was this man? Who was the human behind what a bunch of criminals saw simply as one more mark?

An examination of his Facebook page offers some clues. In addition to happy photos with his twin sons, Tom and Cameron, now about 21, athletic images of Hutch abound — in workout clothes rounding hilly terrain, or beaming over handlebars. Hutch was a frequent participant in “Ironman,” the epically challenging triathlon in which competitors swim 2.4 miles, bike 112 miles and finish it off by running a full 26.2-mile marathon.

Photos show a goofy side too. In one such image, he poses in his official British Transport vest with pink bunny ears. In another, he has photoshopped his face onto a Shaun the Sheep character. He has also posted New Yorker-style cartoons about life’s foibles that reveal a wry outlook. And when he had put on a spiffy suit for a mirror selfie, one friend ribbed him “court case due Hutch?”

It’s a start. I need to push further, reach beneath this social-media surface. But weeks of messages to various family members go unanswered. And I am left in limbo, unable to find out who he was but equally incapable of shaking the feeling that I badly need to.

A hail of DM attempts finally yield a piece of fruit. Well, a hail of DM attempts followed by increasingly bizarre methods of proving I am who I say I am. (Let’s just say holding the day’s newspaper seems quaint by comparison.) But after running the gantlet I finally get an appointment to talk by Zoom with Dave Ashcroft, Hutch’s good friend from Ironman and — would you believe it — a noted anti-fraud investigator.

And he has a lot to say.

“If James — a lot of people called him Hutch; I called him James — would want to be remembered for anything, it’s that he loved the hell out of his kids, that he cared about people, that he had a good sense of humor and what the best finishing time of his Ironman was," he tells me when we start our chat.

“Honestly,” he adds with a laugh, “that’s probably the detail he’d really want to make sure people know about him."

Popular perception has crypto investors as aggressive and troll-happy bros. But that wasn’t Hutch, says Ashcroft. The most dragging he ever did was over Ashcroft’s beloved Everton. (Hutch supported Liverpool.) More often he was showing conviviality, offering affectionate nicknames like "Big Man," to the 6′ 5″ Ashcroft.

Hutch revealed to Ashcroft that the $115,000 was the sum of his savings. “He told me ‘Dave, I lost everything.’ ” (At the end of April 2022, Hutch had also posted to the Facebook group. “All of what I worked for has been taken from me and I feel truly awful,” he wrote. “It has been over a month for me and the gravity of it has hit me really hard.”)

Ashcroft had counseled Hutch that the best chance of recouping the money came not with the scammers or Coinbase but the two English banks from which Hutch had transferred the money, since the banks’ safeguard systems had clearly failed.

Initial letters from the bank rejected the claim, dispiriting Hutch. But Ashcroft believed that within a month or two they could claw it back by appealing their way up to the ombudsmen. He had been through situations like this with other victims and it often worked. “Just give it time,” he told his friend.

Ashcroft, though, wondered if Hutch was really hearing the message. “At some point I’m not sure how much [it] gets through,” he says. “You’re just focused on the fact that this happened to you.” He paused. “It was the shame, really. Shame killed James.”

As a policeman, Ashcroft says, Hutch was far from gullible. But he did have a sweetness about him, and a naivete about digital matters. Suicide is complicated, its causes fraught. But Ashcroft has little doubt the crypto scam marked a breaking point.

“He started using phrases like ‘severe depression,’ and that was unusual for him,” Ashcroft recalls.

To many of us, crypto’s effects barely register. The terms are arcane; the huge sums abstract. What is $5,000,000-worth of bitcoin, anyway, or a trillion-dollar market cap? Mumbo-jumbo on a CNBC crawl.

But reduce the number and the impact paradoxically goes up. The $115,000 taken from Hutch won’t mean much to authorities or the markets. But it meant everything to a dad and retired cop.

The scammers behind Alice had seen Hutch as just one more piece of a blockchain to fatten their digital wallets, technology’s depersonalizing effect. But his vibrancy and humanity was coming through strong.

“For them it’s just a game. And for him he was giving part of himself,” says Sarah Whibley, another close Ironman friend. Ashcroft put me in touch with her. Whibley dated Hutch a number of years ago and remained close with him, the two talking as often as several times a week.

Hutch had a kind of deep-seated tenderness, Whibley said. She found a particular tragedy in this, his greatest asset becoming the tool of his undoing. “He was the kind of person who was very trusting and wore his heart on his sleeve. And of course the scammers can spot that.”

Hutch’s was not a simple existence, Whibley says, owing to a difficult divorce, struggles faced by one of his sons and a stressful job at the transport police, which is a grueling place involving much grimness and little of the prestige of a Scotland Yard

Ironman competitions, in contrast, were his salvation. They gave Hutch both a community and a chance for control, Whibley says. He and others were part of a subset of the extreme-athlete community known as the “Pirates,” and for nearly a decade they would gather across England to support and jibe each other. Hutch, who sometimes went by the oxymoronic online handle “Tough Guy Wabby” (“he was definitely not a tough guy,” says Ashcroft) would often foster the camaraderie among the group.

Whibley says Hutch had left the force a number of months ago, set to retire, but the wipeout from the scam meant he had to start taking odd jobs like housepainting. She says he was wracked by the thought that he now couldn’t provide for his sons. “It kept him up nights in unimaginable ways.”

Cath Hartwell, another Ironman friend, responded to a direct-message on Twitter by saying she was always struck by her friend’s level of sensitivity (“he often phoned for a catch up to see how I was doing after struggling with illness that kept me away from competing”) but also his doggedness. “His ability to never give up during Ironman events was unreal.”

The irony in his ability to stave off his own growing sense of resignation was hard to miss. At one time, Hutch posted to Facebook several times per week. But by the winter of 2022, when he would have been enmeshed in the Alice scam, the posts had trickled to less than one a month.

The last post Hutch offered was March 8. It was simple but effective: a picture of Zelenskyy sitting at his desk in military fatigues. No words, just the image.

It feels like a symbolic choice, a man who’d just been taken advantage of posting the symbol of the man who wouldn’t be exploited. As his own hope for fairness and justice waned, Hutch appeared to be taking heart in the man who was valiantly fighting for it.

And then the account went silent.

THAT OWNERSHIP THING

I am staring at an email draft that I can’t look away from.

Unable to sleep, I have picked up my phone and begun composing a message — the message I would have written to Hutch had I known he was thinking about ending his life. The message that I wish he could have seen just before he stepped out onto those train tracks.

I start writing, telling him the things that he might need to hear from me, a man he doesn’t know but who knows crypto, who has heard many stories from people like him.

“Hi James. Thanks for your note. I just want to say that you are not alone. I don’t mean that in some cliched, generically psychological way. I mean you are literally not alone. The smartest people in the world are losing money on crypto, whether by official scams or otherwise. Doctors. Lawyers. Academics. Wall Street people. It’s too volatile; it’s too unregulated; it’s too subject to manipulations; nobody knows anything. There is no need for shame, or self-loathing. I don’t know if you feel that. But if you do, it totally makes sense. This is at best a mercurial system and at worst a rigged system. Anyway, I don’t know if any of this helps. But you are in extremely good company.”

I think about sending it to his address as some kind of karmic gesture But the pain of knowing that I didn’t send a message like this to him when I had the chance — when it could have still done something — is too much to bear, and I put down my phone.

Journalists are trained on the holy orthodoxy of accountability. If reporters write about bad people enough, and call out enough government officials, the badness could be reduced. And regulation and government intervention are certainly crucial in helping society function more effectively, I believe that strongly.

But a harsh reality also exists — in a world of scammers, some who trust will get hurt, no matter how many laws are in place.

Right under Troy’s email notifying me of Hutch’s death is a pitch from a security company called ActiveFence. The firm, pitching itself to those who’d written about pig-butchering, promises tips to help readers avoid losing money to scams.

The email is filled with truisms like “Check the privacy policy, and make sure it leads to the official app website.” There is something amusingly naive about it, and not just in its implicit assumption that scammers only operate on rogue platforms. The message presupposes that we could simply do away with a victim’s pain if only we are more vigilant — that vulnerability is something that can be checklisted away. But the thousands of victims of the pig-butchering scam like Hutch didn’t forget to read a disclaimer. They simply wanted to believe in love and partnership a little too much.

The last week of May, Ashcroft and Hutch had spoken by phone, ribbing each other a little and then moving on to discussions of their latest strategy to get Hutch’s claim to the bank ombudsmen. The conversation went on for a while, and then it was time to go.

“Thank you, Big Man,” Hutch said to Ashcroft before he hung up. The next night, he stepped onto the tracks.

Ashcroft says even months later he finds it difficult to think about. “There was something about the ‘thank you’ that told me something was wrong."

He grows quiet. “I feel — I don’t know if responsibility is the word — I feel like I knew more than most people but hadn’t done enough. To me, this was completely avoidable.”

His voice catches. “I thought I’d have at least another week.”

My mind also runs through the possibilities of what I could have said during that critical springtime moment when he reached out to tell me something was wrong. I, too, can’t stop wondering if it would have made a difference.

I call Dr. Dan Reidenberg, executive director of the suicide-prevention nonprofit SAVE and a longtime good source on mental-health matters, and explain what happened/what I’m grappling with. “It certainly makes sense that you would feel a sense of responsibility here because you didn’t write back to him,” Reidenberg says. “But unless you were actually able to replenish the money he lost, there’s no reason to believe you would have been able to help him with a note."

He adds, “The truth is as much as we tell people to reach out and ask how someone is doing — and we should — suicide is very complex and not something an outside person can heal." I want to believe him. But I’m not sure I fully can.

One restless night, I decide to take a look at Hutch’s Facebook page. There is an image I hadn’t seen before, from a few years earlier. It’s a reproduction of a flyer of some kind, and it has nothing but text on it. At first it feels like a cruel irony, a message brutally undone by life events. But maybe that's the wrong way to think about it. This isn’t an old message that hindsight proved inaccurate. It's a message being sent now, perhaps even in some spiritual sense by Hutch himself. The lesson is one he had to learn in the most painful way.

But it is one that he, nonetheless, is eager to teach anyone who can still hear it.

It reads:

“Just a reminder in case your mind is playing tricks on you today.

“You matter. You’re important. You’re loved. And your presence on this earth makes a difference whether you see it or not,” all quoted by the man who once completed an Ironman in an extremely brisk 10 hours and 57 minutes.

If you or someone that you know needs help, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988. Crisis Text Line also provides free 24/7confidential support via text message to people in crisis when they text 741741.