Mind and Iron: The Future of Speeding (Yes, Speeding)

Also, an AI disinfo blitz on the Israel-Iran War?

Hi and welcome back to another tangy episode of Mind and Iron. I'm Steven Zeitchik, veteran of The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, senior editor of tech and politics at The Hollywood Reporter and head lifeguard at this newsy pool.

Every week we bring you word from our fast-accelerating future, without spin or hype. Please think about joining our community.

A very happy Juneteenth. What better way to celebrate a holiday than with a little newslettering?

Last week we told you about the future of reading (yes, reading). This week we're taking on a very different but rhyming topic: the future of speeding (yes, speeding). Or, really, what a persistent surveillance state for minor infractions will look like, as 48,000 thousand people who were just ticketed on a Maryland highway without a cop in sight could tell you about.

Also, the Israel-Iran war is one that's hard enough to parse even when consuming wholly reputable sources. What happens when video deepfakes enter the chat? They have, and they risk making a difficult picture cloudier.

And finally, speaking of the future of reading, the New Yorker picked up on said M&I topic this week. We come at the subject from different angles, of course, but worth checking out a piece that also examines what happens to reading and writing when AI pops up as a mediating wall between us and text.

First, the future-world quote of the week:

“We have been seeing a slew of fake videos surrounding the recent conflict between Israel and Iran…being misused to spread misinformation and sow confusion.”

—Cal professor and disinfo expert Hany Farid on the latest dangers far from a battlefield

Let's get to the messy business of building the future.

IronSupplement

Everything you do — and don’t — need to know in future-world this week

Driving as the next surveillance frontier; how do we know what we’re watching from the Middle East is real?

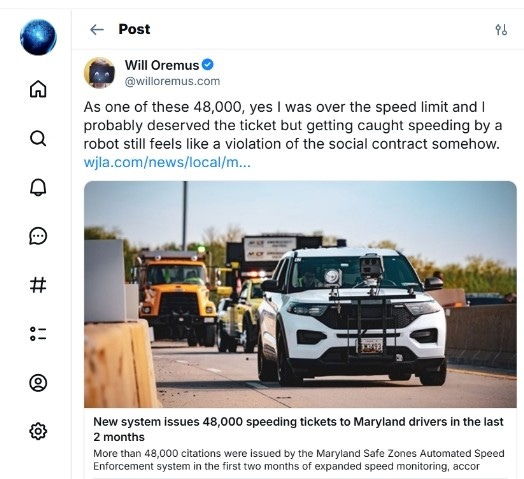

1. A FEW WEEKS AGO, MY OLD PAL AND COLLEAGUE FROM THE POST WILL OREMUS WAS CAUGHT SPEEDING. You may have heard about this, if you spend an inordinate amount of time on Bluesky, or you may not have, if you live a moderately well-adjusted life and try to spend at least 15 percent of it outside.

What was notable not was that he was caught going over the limit on a Maryland highway, nor that he was one of 48,000 people who were similarly ticketed. What was notable was that he had no idea he was being ticketed until some time later when a ticket arrived in the mail. And there it was — going X amount over in a work zone. All captured by a camera he never saw for a violation he may not have even known he had committed. If you briefly zoom then MPH over the limit and there's no one there to stop you, did it really make a sound?

As he posted in the now viral item: "I probably deserved the ticket but getting caught speeding by a robot still feels like a violation of the social contract somehow."

Red-light cameras have been around for decades, causing both privacy concerns and safety concerns. But there is a difference, and it's not just that we're grudgingly used to them. Red-light cameras, or RLC's, sit at a fixed point, and as a society we have made a tacit bargain that we're going to be captured on video when we enter certain spaces. We know we're on camera at a bank, we know we're on camera when we enter a secure office building, we know we're on camera when we climb into an Uber outfitted with a little camera setup (because the app is legally required to tell us).

But riding down a highway is a different ballgame; it's not so much entering a public space as being free of one, of cocooning oneself in the ultimate privacy of one's car and being in the one place outside where surveillance would seem not to apply. Driving down the highway is the ultimate symbol of American freedom. And the idea that a camera is hovering over your shoulder while you enjoy that freedom — hiding right behind your hair as it blows behind you — feels like a trespass into this last sanctuary of public-realm privacy.

The issue is heating up. The subject of SSC's, or Speed Safety Cameras, are likely coming to a legislature near you. Nineteen states and D.C. already allow them; nine explicitly forbid them. (You can probably guess which ones those are — yes, New Hampshire, Texas and West Virginia. Also, New Jersey.) Expect the other 22 states to weigh in soon.

The rationale is clear: as Maryland lieutenant governor Aruna Miller said in the piece Oremus cited, referring particularly to work zones, "Reckless driving at high speeds is a dangerous weapon in motion. Every second of carelessness on the road can steal a lifetime from someone else." Enter SSC's as a deterrent.

Now whether they actually make the road safer is still unknown. Red-light cameras of course may not: many people don't know they're there so their deterrent factor is nil. And those that do, studies have shown, will brake suddenly, causing collisions and wiping out the supposed benefits.

But even if they are proven to slow down drivers and make roads safer, SSC's aren't so simple. Oremus' post, especially his comment about the robot-ticket as a violation of the social contract, engendered a whole lot of finger-wagging, a Kramer-esque 'don't do the crime if you can't do the time' clucking. But of course the cameras raise a philosophical question that goes well beyond a pesky ticket, one we'll probably want to resolve sooner than later in our new stealth surveillance world — namely, how much are we willing to allow constant monitoring in the name of a better society? Because we really do have two competing values here: a desire to build a safer and better world coming up against a desire not to have the police camping out on our shoulders.

Or, put another way: how much are we comfortable with feeling less private when we step outside the house in exchange for the knowledge that we'll be stepping into a place slightly less dangerous? “Judgy nanny-stater” and “reckless libertarian” are the kinds of tags we'll throw at each other, but there's really no easy personal argument, let alone societally uniform answer.

Not to mention the whole witness-less thing. From ancient legal codes to modern statutes, we tend to prefer when we can face our accuser. And yet, as the classic RLC criticism has it, no accuser comes forth.

SSCs are just the start of these kinds of flashpoints. A number of MLB teams from Philly to SF have begun to implement a facial-recognition entry system that will (they say) move lines faster and (they also say) make attendance at a game safer.. Right now it's opt-in, but these things have a funny way of becoming standard.

Those systems pose the same question: do we want, as a society, for a corporation like MLB to own our biometrics so we can get in to a game a few minutes faster? OK, I kind of stacked the deck on that one; there may be some security benefits. But there also may be tons of abuses. I mean, look at how MSG used facial recognition to ban lawyers it didn't like from the World's Most Famous.

I don't think there are easy answers — certainly a facial-recognition system at airports and border checkpoints, as we increasingly are seeing, seems faster and hopefully more likely to catch people up to no good. But we also know too well the bias, pitfalls and injustices that come with them.

One last philosophical point percolates here: the Silicon Valley value of efficiency and the economy that flows from it. What the hell am I talking about? Well, speeding tickets right now operate with an almost biological sense of balance: they're a tax, but one that is levied with some checks. To collect it, a government needs to send some cops to the side of the road, then they need to clock you, stop you and issue the ticket. They need humans. All of that can seem inefficient, but it actually has a self-regulating effect: it means that only a certain number of people are getting speeding tickets on a given stretch of road over a given period.

When you remove all those limitations and just ticket anyone anywhere going over the speed limit, what you're basically doing is imposing a new tax. You're making to so easy for the government to give speeding tickets that it's really (given how many people accelerate past the limit as some point over a commute or long drive) just a way of saying we need to ship a certain amount of our paycheck to the government whenever we step into our cars.

I think that's what Oremus is getting at when he’s saying it's a violation of the social contract (I messaged Will but he's been tortured enough on this subject for one lifetime).

Inefficiency isn't good, sure. But also, is efficiency-on-steroids a value we want to embrace? If every person gets a ticket every time they accelerate in the left lane to pass someone, have we jumped the AI shark? Is that really how we want to use automated systems? Has tech made public life so efficient it can seem painful to be alive?

These are tricky issues, and one can certainly see the value of a system that will bring more safety. But like so much else future-related, the costs and unintended consequences are great, and we tend not to look for them until we’ve rounded a blind curve and hit them smack in the face.

2. ANY WAR IN THIS CUTTING-EDGE ERA COMES WITH THE THREAT OF NEW WEAPONS, AND NOT JUST ON THE BATTLEFIELD.

Informational weapons can be just as dangerous too, as we know well from the past few years of conflict in Ukraine and Gaza. Elephantine readers will recall an item we did in the early days of the Israel-Hamas war when images of people in both Israel and Gaza, along with photos of supporters of various kinds from around the world, came at us so fast and confusingly it was impossible to tell what was real and what wasn't. (Flip through them at IG speed and see if, even now, you can tell the difference.) Israel-Gaza was the first war of AI images. And it has blitzed us mightily.

A lot has happened in the world of tech since that conflict began. Some of the biggest changes involve short-form AI video, which back in 2023 barely existed. Such videos are still pretty short — continuity between scenes is hard. But synthetic videos that can masquerade as genuine news clips are becoming more viable. Plus their makers are good at figuring out ways around the non-viability. Here's an example of one, of Iranians supposedly chanting "We Love Israel" in the streets of their country. Notice how for much of the video you don't see a closeup, so no need to make lips match sounds.

No quizzes here — this one is definitely AI-generated. Still, it's not a manifestly obvious fake, certainly not to someone bombarded with a whole bunch of TikTok clips. And it's only the beginning.

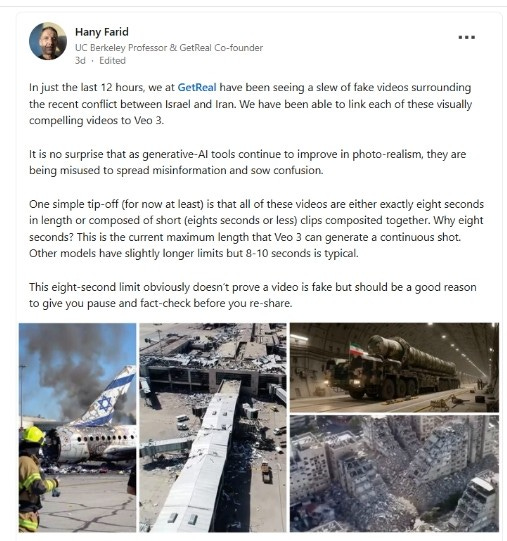

M&I friend and Cal professor Hany Farid has been one of the leading researchers into the dangers of synthetic media in our news landscape, on everything from elections to wars, and has even recently started a company called GetReal to detect them. As he posted to LinkedIn this week, a number of videos, most of which seem to use the Google tool Veo 3,have been popping up — scenes of invented destruction intended to rally a group to excitement or anger. (Those airport ones are part of a deepfake clip purporting to show Israel’s Ben-Gurion airport destroyed.)

Videos are a whole new frontier in the truth-muddling business. After decades of Photoshop we're naturally skeptical of images. But we’re still pretty credulous when it comes to video. Largely that's for good reason — with so many more frames to give you away, videos are a lot harder to fake. What that does, though, is open up a window, until our credulousness evaporates, for bad actors to jam into our minds all kinds of deceptive AI videos that they can’t with AI-generated images. We're simply a lot more likely to trust videos. Plus they're shown scientifically to embed in our brains in a different way.

What's worse is that one hardly needs a massive content operation to generate these. Many AI videos are unauthored and come from individuals. As Farid told us in an interview last year, "If pretty much anybody can create content that is this deceptive we are in trouble, as a democracy and a society. Because it will be very easy to manipulate people with disinformation."

Sure, there are giveaways; as Farid notes, nearly all the ones he dug up are almost exactly eight seconds (most tools can't go beyond that without risking the continuity issue). But most of us don't have a stopwatch, and it's hardly dispositive anyway.

The dangers of a disinfo attack are many. There are the obvious perils of thinking something that happened didn't, and getting outraged and vocal as a result, which in turns spurs more outrage and vocality. But deception is actually only part of the problem. Because even when we know an image is synthetic we still run into trouble.

First, we stop trusting even real images when we've been exposed to too many known fakes (social scientists call this the liar's dividend.") As all this goes on, AI becomes a battleground itself — first a combatant puts out disinformation via AI, then the enemy cites AI as its own rebuttal, so pretty soon everyone is crying synthetic and no one knows what the truth is.

That already sort of played out this week when, after a number of these apparent deepfakes proliferated, Israeli military spokesman Nadav Shoshani went on NewsNation on Wednesday to tell Elizabeth Vargas that "the Iranians do not have not a lot of achievements and it's very clear when you don’t have a lot of achievements you start pushing out fake news, you start creating AI images that portray victories, you start telling everybody an F-35 has collapsed."

(It’s tough to know how much of this is truly state-sponsored, though it’s certainly plausible some of it is, regardless of side; as this colorful Medium commentator noted of the Iranian one, “As Israeli jets target ‘propaganda infrastructure’ and the world scrambles to verify what’s real, Iran’s digital commandos are busy launching viral disinformation, hijacking social media feeds, and unleashing AI-powered deepfakes that muddy the truth in the fog of war. Forget tanks. Forget even missiles. In this new phase of the Israel-Iran conflict, TikTok, Telegram, and Twitter are the front lines — and your grandma’s probably retweeting regime propaganda between cat videos and turmeric recipes, as the battle for hearts and minds rages at meme speed.”)

And there’s another turn of the screw: even when we know an image is fake, if it's mixed in with genuine ones our brains tend to internalize it as real. This upsetting truth comes courtesy of a UC Irvine psychologist named Elizabeth Loftus, whose research has found that when known fakes are mixed in to our childhood family photos — say, an image of a trip to Disneyland we never took — we still can recall the trip as having happened. So simply labeling or identifying something as AI doesn't remove the risks.

All of this means that the dangers are growing with every advancement in synthetic video. There's some slight reassurance in the form of a 2021 MIT study that found that when it comes to persuasion, video holds only a slight advantage over text. And there are companies, like Farid’s, that are springing up to root out the fakes. But whether platforms will use them — whether we want to use them — remains unclear.

I believe a lot of us do want to know facts, and even the most polarized in my own circle will often, reluctantly, say they're glad I told them that an ideology-reinforcing “fact” is actual total hogwash. (The curse of knowing a journalist.)

But I've noticed that the times some friends simply shut out such gentle reminders are getting more frequent, and the work I have to do move them off the fact they're utterly convinced of is growing. The reality is most of us are becoming more unwilling to cut through the thicket to know what’s behind it, in part because the world is hard and opponents are many and it would be nice to be reassured sometimes, and in part because that thicket is becoming ever more tangled.

The quality of the tech and the ferocity of bad actors are concerning. But they're only part of the challenge. The other part is how we react to these factors. Our media landscape requires an ever-greater effort to know the facts. And how much do we want to work to learn an uncomfortable truth when we can sit back and bask in an enjoyable fiction?

The Mind and Iron Totally Scientific Apocalypse Score

Every week we bring you the TSAS — the TOTALLY SCIENTIFIC APOCALYPSE SCORE (tm). It’s a barometer of the biggest future-world news of the week, from a sink-to-our-doom -5 or -6 to a life-is-great +5 or +6 the other way. This year started on kind of a good note. But it’s been fairly rough since. This week? Even rougher.

HERE COME THE SPEEDING CAMERAS: -2.0

WARTIME DEEPFAKES, VIDEO EDITION: -4.0